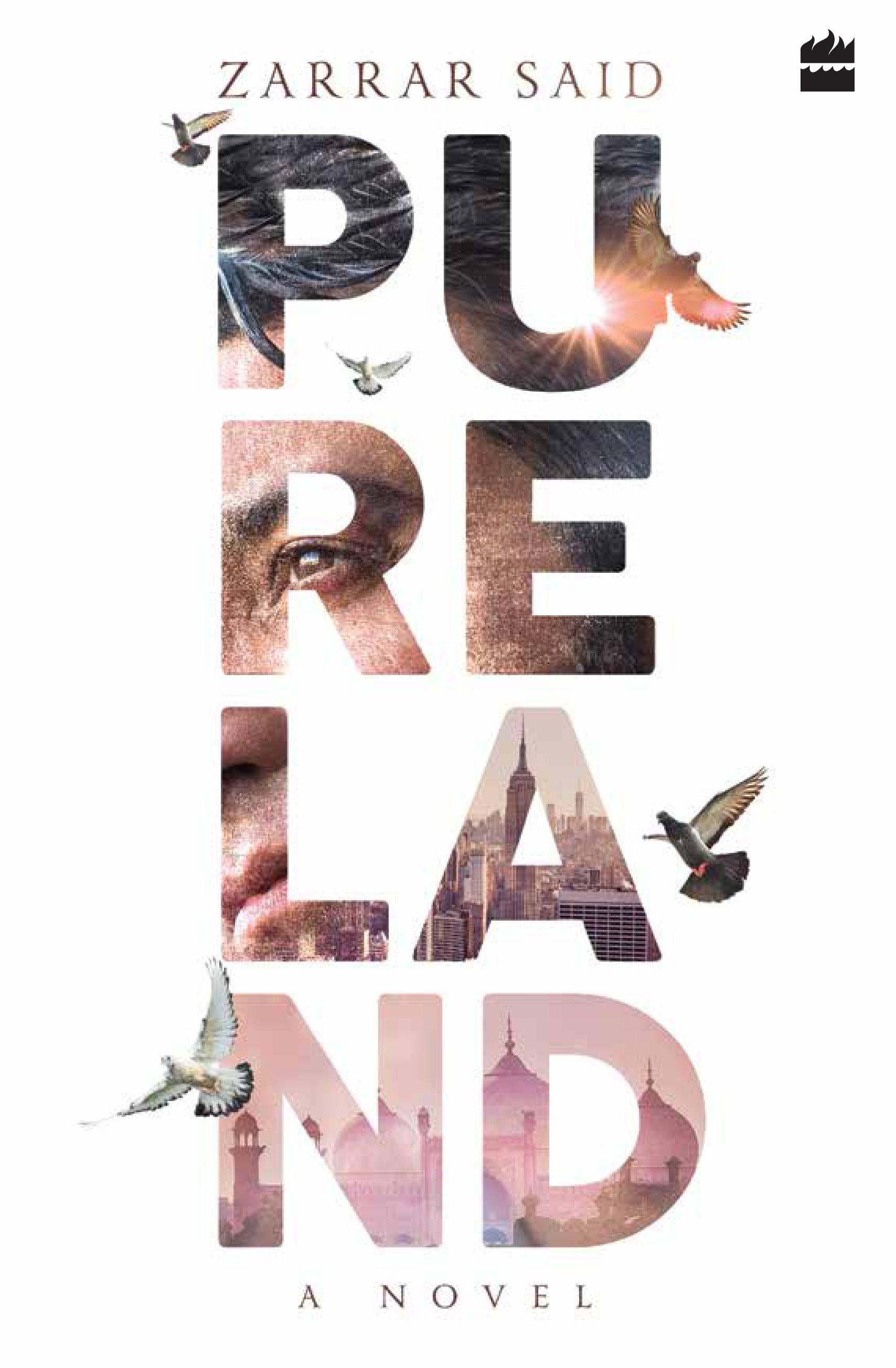

Pureland

Zarrar Said

|

|

In November 1970, while a cyclone sweeps Bangladesh’s shores, Honufa scurries from her hut in a Chittagong fishing village with her three-year-old son, Shahryar, attempting to reach the safety of the mansion of the zemindar, Rahim. Decades later, Shahryar is in Washington, DC driving his nine-year-old daughter, Anna, to the home of her mother, Valerie. Anna is distraught; Shahryar, having completed his PhD and unable to secure permanent employment, is required to leave the US. Shahryar hires a shady lawyer for advice on various options—some illegal—to remain in the US.

M.A. Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan and its greatest leader, was by no means a devout Muslim. As everyone knows, he married a non-Muslim, preferred a ‘Westernised’ life, did not speak either Gujarati or Urdu fluently, and had to be posthumously cemented into the dominant Sunni regime of faith by his followers. Perhaps, had Jinnah been religious, he might not have been able to believe, as he and many like him obviously did, that you could demand a nation in the name of religion and expect it to stay essentially secular or at least fair to people of other faiths! Guardian angel The book is dedicated to the late Dr. Abdus Salam — “who loved a nation that never loved him back” — and the storyline as well as the blurb try to highlight this connection. Like Dr. Salam, Salim Agha, the protagonist of Pureland, is a child prodigy from the provinces born into the Ahmadiyya community (ostracised in Pakistan) who goes on to win the Nobel Prize for physics. But the historical Dr. Salam was very much an integral part of the Pakistani scientific community, and considered the “father” of the country’s successful nuclear programme, although in 1974 he did choose to leave Pakistan in protest after the passage of a bill declaring members of the Ahmadiyya movement to be non-Muslims. However, unlike Agha, he was not murdered. He died peacefully in bed, and in 1998 Pakistan even issued a commemorative stamp in Dr. Salam’s honour. In some ways, despite the blurb, Pureland is informed less by the ghost of Dr. Salam than by the very living spirit of Salman Rushdie. For one, though Said judiciously avoids Rushdie’s linguistic gymnastics, this book returns us to the magic realist genre as political parable. One can even find some familiar characters and connections: the levitating fakir, the witch-like mother or grandmother, the generous and feudal general, the beautiful and headstrong heiress, the hero born with supernatural powers (or, in this case, the child prodigy), the lecherous servant, the river of stories, multiple fathers, etc. Grappling with politics Finally, it is Said’s attempt to grapple with the politics of Pakistan that makes this novel noticeable, apart from the fact that it signifies a promising first attempt. I am not sure that magic realism is the best of ways to grapple with politics — though, of course, every postcolonial magic realist writer claims that he is doing something else these days — but it did become a valid option with Midnight’s Children. Rich dividends But let literary-type critics carp-varp. Magic realist texts have offered options to narrate the political in postcolonial contexts, which — as Rushdie showed in Midnight’s Children and Shame — can lead to rich dividends. Pureland does not reach the level of Rushdie at his inimitable best, and yet it combines a racy narrative with political insight and commentary: “You could feel it, growing up, that Pureland was in some way being set up for the Caliphate to take over. We felt it many years earlier. In fact, before the turban-clad army blew through our cities with AK-47s slung over their shoulders, we were in a way, expecting them.” I guess that might be the difference between people like Jinnah in the past and people like Said today. Jinnah, after all, did not seem have expected any turban-clad army to take over Pakistan. I suppose Jinnah was like us in India today: we cannot envision any whatever-clad army taking over our secular and democratic nation. I am sure we have no reason to. Tabish Khair is an Indian novelist and academic who teaches in Denmark.

|