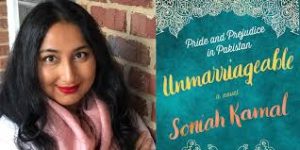

Book Excerpt: Unmarriageable by Soniah Kamal

Chapter 1

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a girl can go from pauper to princess or princess to pauper in the mere seconds it takes for her to accept a proposal.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a girl can go from pauper to princess or princess to pauper in the mere seconds it takes for her to accept a proposal.

When Alysba Binat began working at age twenty as the English-literature teacher at the British School of Dilipabad, she had thought it would be a temporary solution to the sudden turn of fortune that had seen Mr. Barkat “Bark” Binat and Mrs. Khushboo “Pinkie” Binat and their five daughters—Jenazba, Alysba, Marizba, Qittyara, and Lady—move from big-city Lahore to backwater Dilipabad. But here she was, ten years later, thirty years old, and still in the job she’d grown to love despite its challenges. Her new batch of ninth-graders was starting Pride and Prejudice, and their first homework had been to rewrite the opening sentence of Jane Austen’s novel, always a fun activity and a good way for her to get to know her students better.

After Alys took attendance, she opened a fresh box of multicolored chalks and invited the girls to share their sentences on the blackboard. The first to jump up was Rose-Nama, a crusader for duty and decorum, and one of the more trying students. Rose-Nama deliberately bypassed the colored chalks for a plain white one, and Alys braced herself for a reimagined sentence exulting a traditional life—marriage, children, death. As soon as Rose-Nama ended with mere seconds it takes for her to accept a proposal, the class erupted into cheers, for it was true: A ring did possess magical powers to transform into pauper or princess. Rose-Nama gave a curtsy and, glancing defiantly at Alys, returned to her desk.

“Good job,” Alys said. “Who wants to go next?”

As hands shot up, she glanced affectionately at the girls at their wooden desks, their winter uniforms impeccably washed and pressed by dhobis and maids, their long braids (for good girls did not get a boyish cut like Alys’s) draped over their books, and she wondered who they’d end up becoming by the end of high school. She recalled herself at their age—an eager-to-learn though ultimately naïve Ms. Know-It-All.

“Miss Alys, me me me,” the class clown said, pumping her hand energetically.

Alys nodded, and the girl selected a blue chalk and began to write.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a young girl in possession of a pretty face, a fair complexion, a slim figure, and good height is not going to happily settle for a very ugly husband if he doesn’t have enough money, unless she has the most incredible bad luck (which my cousin does).

The class exploded into laughter and Alys smiled too.

“My cousin’s biggest complaint,” the girl said, her eyes twinkling, “is that he’s so hairy. Miss Alys, how is it fair that girls are expected to wax everywhere but boys can be as hairy as gorillas?”

“Double standards,” Alys said.

“Oof,” Rose-Nama said. “Which girl wants a mustache and a hairy back? I don’t.”

A chorus of, I don’ts filled the room, and Alys was glad to see all the class energized and participating.

“I don’t either,” Alys said complacently, “but the issue is that women don’t seem to have a choice that is free from judgment.”

“Miss Alys,” called out a popular girl. “Can I go next?”

It is unfortunately not a truth universally acknowledged that it is better to be alone than to have fake friendships.

As soon as she finished the sentence, the popular girl tossed the pink chalk into the box and glared at another girl across the room. Great, Alys thought, as she told her to sit down; they’d still not made up. Alys was known as the teacher you could go to with any issue and not be busted, and both girls had come to her separately, having quarreled over whether one could have only one best friend. Ten years ago, Alys would have panicked at such disruptions. Now she barely blinked. Also, being one of five sisters had its perks, for it was good preparation for handling classes full of feisty girls.

Another student got up and wrote in red:

It is a truth universally acknowledged that every marriage, no matter how good, will have ups and downs.

“This class is a wise one,” Alys said to the delighted girl.

The classroom door creaked open from the December wind, a soft whistling sound that Alys loved. The sky was darkening and rain dug into the school lawn, where, weather permitting, classes were conducted under the sprawling century-old banyan tree and the girls loved to let loose and play rowdy games of rounders and cricket. Cold air wafted into the room and Alys wrapped her shawl tightly around herself. She glanced at the clock on the mildewed wall.

“We have time for a couple more sentences,” and she pointed to a shy girl at the back. The girl took a green chalk and, biting her lip, began to write:

It is a truth universally acknowledged that if you are the daughter of rich and generous parents, then you have the luxury to not get married just for security.

“Wonderful observation,” Alys said kindly, for, according to Dilipabad’s healthy rumor mill, the girl’s father’s business was currently facing setbacks. “But how about the daughter earn a good income of her own and secure this freedom for herself?”

“Yes, Miss,” the girl said quietly as she scuttled back to her chair.

Rose-Nama said, “It’s Western conditioning to think independent women are better than homemakers.”

“No one said anything about East, West, better, or worse,” Alys said. “Being financially independent is not a Western idea. The Prophet’s wife, Hazrat Khadijah, ran her own successful business back in the day and he was, to begin with, her employee.”

Rose-Nama frowned. “Have you ever reimagined the first sentence?”

Alys grabbed a yellow chalk and wrote her variation, as she inevitably did every year, ending with the biggest flourish of an exclamation point yet.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single woman in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a husband!

“How,” Alys said, “does this gender-switch from the original sentence make you feel? Can it possibly be true or can you see the irony, the absurdity, more clearly now?”

The classroom door was flung open and Tahira, a student, burst in. She apologized for being late even as she held out her hand, her fingers splayed to display a magnificent four-carat marquis diamond ring.

“It happened last night! Complete surprise!” Tahira looked excited and nervous. “Ammi came into my bedroom and said, ‘Put away your homework-shomework, you’re getting engaged.’ Miss Alys, they are our family friends and own a textile mill.”

“Well,” Alys said, “well, congratulations,” and she rose to give her a hug, even as her heart sank. Girls from illustrious feudal families like sixteen-year-old Tahira married early, started families without delay, and had grandchildren of their own before they knew it. It was a lucky few who went to college while the rest got married, for this was the Tao of obedient girls in Dilipabad; Alys went so far as to say the Tao of good girls in Pakistan.

Yet it always upset her that young brilliant minds, instead of exploring the universe, were busy chiseling themselves to fit into the molds of Mrs. and Mom. It wasn’t that she was averse to Mrs. Mom, only that none of the girls seemed to have ever considered traveling the world by themselves, let alone been encouraged to do so, or to shatter a glass ceiling, or laugh like a madwoman in public without a care for how it looked. At some point over the years, she’d made it her job to inject (or as some, like Rose-Nama’s mother, would say, “infect”) her students with possibility. And even if the girls in this small sleepy town refused to wake up, wasn’t it her duty to try? How grateful she’d have been for such a teacher. Instead, she and her sisters had also been raised under their mother’s motto to marry young and well, an expectation neither thirty-year-old Alys, nor her elder sister, thirty-two-year-old Jena, had fulfilled.

In the year 2000, in the lovely town of Dilipabad, in the lovelier state of Punjab, women like Alys and Jena were, as far as their countrymen and -women were concerned, certified Miss Havishams, Charles Dickens’s famous spinster who’d wasted away her life. Actually, Alys and Jena were considered even worse off, for they had not enjoyed Miss Havisham’s good luck of having at least once been engaged.

As Alys watched, the class swarmed around Tahira, wishing out loud that they too would be blessed with such a ring and begin their real lives.

“Okay, girls,” she finally said. “Settle down. You can ogle the diamond after class. Tahira, you too. I hope you did your homework? Can you share your sentence on the board?”

Tahira began writing with an orange chalk, her ring flashing like a big bright light bulb at the blackboard—exactly the sort of ring, Alys knew, her own mother coveted for her daughters.

It is a truth universally acknowledged in this world and beyond that having an ignorant mother is worse than having no mother at all.

“There,” Tahira said, carefully wiping chalk dust off her hands. “Is that okay, Miss?”

Alys smiled. “It’s an opinion.”

“It’s rude and disrespectful,” Rose-Nama called out. “Parents can never be ignorant.”

“What does ignorant mean in this case, do you think?” Alys said. “At what age might one’s own experiences outweigh a parent’s?”

“Never,” Rose-Nama said frostily. “Miss Alys, parents will always have more experience and know what is best for us.”

“Well,” Alys said, “we’ll see in Pride and Prejudice how the main character and her mother start out with similiar views, and where and why they begin to separate.”

“Miss Alys,” Tahira said, sliding into her seat, “my mother said I won’t be attending school after my marriage, so I was wondering, do I still have to do assign—”

“Yes.” Alys calmly cut her off, having heard this too many times. “I expect you to complete each and every assignment, and I also urge you to request that your parents and fiancé, and your mother-in-law, allow you to finish high school.”

“I’d like to,” Tahira said a little wistfully. “But my mother says there are more important things than fractions and ABCs.”

Alys would have offered to speak to the girl’s mother, but she knew from previous experiences that her recommendation carried no weight. An unmarried woman advocating pursuits outside the home might as well be a witch spreading anarchy and licentiousness.

“Just remember,” Alys said quietly, “there is more to life than getting married and having children.”

“But, Miss,” Tahira said hesitantly, “what’s the purpose of life without children?”

“The same purpose as there would be with children—to be a good human being and contribute to society. Look, plenty of women physically unable to have children still live perfectly meaningful lives, and there are as many women who remain childless by choice.”

Rose-Nama glared. “That’s just wrong.”

“It’s not wrong,” Alys said gently. “It’s relative. Not every woman wants to keep home and hearth, and I’m sure not every man wants to be the breadwinner.”

“What does he want to do, then?” Rose-Nama said. “Knit?”

Alys painstakingly removed a fraying silver thread from her black shawl. Finally she said, in an even tone, “You’ll all be pleased to see that there are plenty of marriages in Pride and Prejudice.”

“Why do you like the book so much, then?” Rose-Nama asked disdainfully.

“Because,” Alys said simply, “Jane Austen is ruthless when it comes to drawing-room hypocrisy. She’s blunt, impolite, funny, and absolutely honest. She’s Jane Khala, one of those honorary good aunts who tells it straight and looks out for you.”

Alys erased the blackboard and wrote, Elizabeth Bennet: First Impressions?, then turned to lead the discussion among the already buzzing girls. None of them had previously read Pride and Prejudice, but many had watched the 1995 BBC drama and were swooning over the scene in which Mr. Darcy emerged from the lake on his Pemberley property in a wet white shirt. She informed them that this particular scene was not in the novel and that, in Austen’s time, men actually swam naked. The girls burst into nervous giggles.

“Miss,” a few of the girls, giddy, emboldened, piped up, “when are you getting married?”

“Never.” Alys had been wondering when this class would finally get around to broaching the topic.

“But why not!” several distressed voices cried out. “You’re not that old. And, if you grow your hair long again and start using bright lipstick, you will be so pret—”

Chapter Five

At the dessert table, Jena, Alys, and Sherry wished they’d eaten a little less dinner. Still, they managed to sample everything: gulab jamuns in sweet sticky syrup, firni gelled in clay ramekins and decorated with edible silver paper, snow-white ras malai, tiramisu cups and lemon custard tarts, kulfi ice cream and sweet paans from a kiosk preparing them fresh on the spot, the bright-green betel leaves stuffed with shredded coconut, betel nuts, fennel, rose-petal jam, sugar syrup, and then folded into perfect triangles.

Jena was taking a dainty bite of an unsweetened paan when she was approached by two girls with cascades of highlighted hair. Some extensions, for sure, she thought, and a healthy amount of makeup, just shy of too much. They were dressed exquisitely in heavily embroidered lehenga cholis with their flat midriffs bare, and diaphanous dupattas, clearly the work of an established designer. Jena noticed their single-strap matte-silver heels. She’d been searching for shoes like these, but all she’d been able to find were horrendous wide-strapped glittery platforms.

“Where did you get your shoes?” Jena asked, smiling her admiration.

“Italy,” one of the girls said. “I love the detailing on your sari blouse and border. Whose is it?” She rattled off a few designer names.

Jena shook her head. “No designer. My tailor, Shawkat. He has a small shop in Dilipabad Bazaar.”

“Oh, I see.” The girl’s face fell for a second. “I’m Humeria Bingla—Hammy.”

“And I’m Sumeria Bingla—Sammy,” said the other girl. “Actually, Sumeria Bingla Riyasat. I’m married. Happily married.”

“Jena Binat,” Jena said. She proceeded to introduce Alys, Mari, and Sherry. Hammy turned to Sherry with a huge smile.

“Are you Sherry Pupels from the Peshawar Pupels clan?” she asked. “The politician’s wife?”

“No,” Sherry said. “I am Sherry Looclus from Dilipabad, born and bred.”

Alys would swear Hammy-Sammy’s noses curled once they realized that Sherry was not the VIP they’d mistaken her for.

“Hi.” It was the sweet-looking sandy-haired fellow.

“And this,” Hammy said, turning as if the interruption was preplanned, “is our baby brother, Bungles.”

“Fahad Bingla,” he said.

“Bungles,” Hammy said firmly. “Because, when we were children, he kept bungling up every game we’d play, right, Sammy?”

“Right, Hammy,” Sammy said.

“And,” Hammy said, “he’d still keep bungling up if Sammy and I didn’t keep him in check.”

Bungles laughed and shook his head. He held his hand out to Jena. Jena shook it and Bungles held on for a second too long. Jena blushed. Bungles shook hands with Alys and Sherry, but Mari wouldn’t shake his hand, because, she said, Islam forbade men and women touching.

“Are you all very Islamic?” Hammy said.

“Clearly not,” Alys said, a little annoyed, though she wasn’t sure whether it was at Mari’s self-righteous piety or Hammy’s supercilious tone. “Anyway, this is Pakistan. You’ve got very religious, religious, not so religious, and nonreligious, though no one will admit the last out loud, since atheism is a crime punishable by death.”

“What a font of knowledge you are, babes!” Hammy said. “Isn’t she, Sammy?”

“She is,” Sammy said, as she turned to a stocky man lumbering toward her with a cup of chai. “All, this is my husband, Sultan ‘Jaans’ Riyasat. He’s thinking about entering politics. Jaans, all.”

Jaans gave a short wave before plopping into a nearby chair, his stiff shalwar puffing up around him. He patted the empty seat beside him. Sammy glided over, perching prettily, ignored the fact that Jaans was taking huge swigs from a pocket liquor flask. She proceeded to take elegant sips of her chai.

The out-of-town guests had come to Dilipabad to attend the mehndi ceremony tonight and the nikah ceremony the next day and were staying at the gymkhana.

“So basically, babes, we’re bored,” Hammy said. “We got into Dilipabad two days ago, because Nadir wanted to make sure everyone was here, but there’s literally nothing to do. We went to that thing this town calls a zoo, with its goat, sheep, camel, and peacock. And we went to the alligator farm and stared at alligators, who stared back at us, and I told them you can’t eat me but I’ll see you in Birkin. And Nadir and Fiede arranged for a hot-air-balloon tour over what amounted to villages and fields.”

“The hot-air balloon sounds like fun,” Alys said. “A bit of Oz in Dilipabad. You know, The Wizard of Oz?”

“Babes, for real, it was all green and boring,” Hammy said. “What do you locals do for fun in D-bad?”

“We have three restaurants,” Jena said. “And a recently opened bakery-café, High Chai.”

“Oh dear God!” Sammy said. “Fiede took us there yesterday.”

“There was a hair in my cappuccino,” Hammy said. “A long, disgusting hair.”

“And the place smelled like wet dog,” Sammy said.

“We’ve been multiple times and everything was quite lovely,” Jena said. “Nothing but the scent of freshly baked banana bread. And the staff wore hairnets and gloves.”

“Oh my goodness, Jena!” Hammy took Jena’s hand and stroked it as if she was speaking to a child. “The hair was bad enough, but the Muzak was some crackly throwback tape that played ‘Conga’ and ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun’ on repeat. Get with it, D-bad. It’s the year 2000.”

Alys was suddenly offended on behalf of “D-bad.”

“I’m sure the hair was an aberration,” she said. “And you should have asked them to change the songs.”

“Oh,” Hammy said. “We abhor being a bother!”

“Yes,” Sammy said. “We’re guests. Passers-through. If you locals are happy with the state of things, why should we try to change anything? We can live without fun for a few days. Right, Hammy?”

“Right, Sammy,” Hammy said. “Boredom is a bore, not a killer.”

“And what,” Alys asked, “according to you constitutes fun?”

Before Hammy-Sammy could answer, Lady, Qitty, and the fine-eyed guy on the dance floor descended upon the group at the same time. Alys glanced at him. His eyes were intensely black, with thick lashes their mother always claimed were wasted on men, as was his jet-black hair, which fell neatly in a thick wave just below his ears. He was taller than Bungles and had broader shoulders. He frowned and glanced at his expensive watch, and Alys noted that he had sturdy forearms and nice strong hands. Lovely hands.

“Hello,” Lady said. She was carrying a bowl full of golden fried gulab jamuns. “Have you tried these? To die for. Isn’t this the best wedding ever? I have a good mind to tell Fiede to get married every year.”

“Is that so?” Hammy said. “I’m sure Fiede will be thrilled at your suggestion. And who are you?”

“Aren’t you,” Sammy said, “the girl who crashed the dance floor?”

Lady nodded, unabashed, even though her sisters cringed.

“I’m Lady, their sister.” Lady pointed to Jena, Alys, and Mari. “And this is our other sister, Qitty.”

“I can speak for myself,” Qitty said. “Hello.”

“But a moment ago,” Lady said, “you told me you’d eaten so much you could no longer speak.”

“Because I didn’t want to speak to you,” Qitty said.

“Qitty!” Alys said. “Lady!”

“Ladies’ Room,” Jaans called from his chair. “Everyone wants to go to the Ladies’ Room. Is it open?”

“Oh, you!” Sammy smacked her husband on his hand. “Such a joker.”

The guy with the intense eyes and lovely hands, Alys noted, was watching as if he’d decided the entire world was a bad comedy and it was his punishment to witness every awful joke.

“Bungles,” he said, “if you’re done entertaining yourself, can we—”

Bungles interrupted him. “This is one of my best friends, Valentine Darsee.”

“Valentine,” Hammy said, “say a big hearty hello to the sisters Binat and their friend Cherry.”

“Sherry,” Sherry said, flushing.

“Sherry,” Hammy said. “My sincere apologies.”

Darsee seemed to be taking his time giving them a big hearty hello, Alys thought, but before he could get to it, Lady began to laugh uncontrollably.

“Valentine!” Lady doubled over. “Were you born on Valentine’s Day?”

Spittle sprayed out of Lady’s mouth, and Darsee and Hammy jumped out of the way, revulsion on their faces.

“Lady!” Jena said, mortified.

“Oops!” Lady wiped her mouth with the back of her hand. “Sorry. Sorry.”

“I’m sure you are,” Hammy said. “But I’m not sure I’m getting the joke. Valentine is such a romantic name.”

Everyone waited for Darsee to say something, but after several moments Bungles spoke up.

“Valentine’s late mother,” Bungles said, “was a big fan of Rudolph Valentino, and she named him Valentino. The staff at the hospital mistook it for Valentine and, by the time anyone checked, the birth certificate was complete and so that was that, right, Val?”

Valentine Darsee gave a curt nod. It was unclear to Alys whether he couldn’t care less if they knew the origin story of his name or whether Lady’s spittle had caused him severe trauma.

“Same thing happened with Oprah,” she offered in a conciliatory tone.

“Pardon me?” Darsee said, as if he was seeing her for the first time and not liking what he saw.

“Oprah. She was named Orpah, after a character in the Bible, but her name was mistakenly recorded as Oprah.” Alys added, “I read it in Reader’s Digest, I think, or Good Housekeeping.”

Darsee turned to Bungles. “I’m going to check in with Nadir for the night and then head back to our room.”

He left without a smile, without a “pleased to meet you,” without even a cursory nod. Hammy at least nodded at the group before running after him. Lady decided to get more gulab jamuns and dragged Qitty with her. Sammy and Jaans turned to each other. Bungles explained, sheepishly, that Darsee had recently arrived from Atlanta, where he’d been studying for an MBA, and was still jet-lagged. Alys and Sherry exchanged a look: Valentine Darsee was the British School Group.

“Jena,” Bungles said. “Can I get you some chai? Dessert? Anything?”

“Jena,” Sherry said, “why don’t you and Bungles Bhai go get chai together?”

Bungles thought this a fabulous idea, and Jena, with no reason to refuse, walked with him to the tea table, where teas, pink, green, and black, were being served.

“That was obvious,” Alys said. “A great ‘grab it’ move. My mother will be so proud of you.”

“You and Jena need to listen to your mother once in a while,” Sherry said. “Clearly Bungles Bhai is interested in Jena, and she needs to show a strong interest in return.”

“She just met him,” Alys said. “Two minutes ago.”

“So?” Sherry said. “If she doesn’t show interest, a million other girls will.”

“If he’s going to lose interest because she’s modest, then perhaps he’s not worth it.”

“Of course he’s worth it. And aren’t you the sly one to use the word ‘modest.’ ”

“Huh?”

“ ‘Modest sanitary napkins for your inner beauty, aap ke mushkil dinon ka saathi, the companion of your hard days,’ ” Sherry said, spouting the jingle that played during the animated advertisement for Modest sanitary products. “Bungles, Hammy, and Sammy are Modest. They own the company. I recognize them from interviews. And soon our Jena will be Mrs. Modest.”

“You’ll be naming their children next.” Alys shook her head. “They barely know each other.”

“Plenty of time for them to get to know each other once they’re married.”

“I think,” Alys said, “better to get to know each other before deciding to get married.”

“Big waste of time,” Sherry said. “Trust me, everyone is on their best behavior until the actual marriage, and then claws emerge. From what I’ve gleaned, real happiness in marriage seems a matter of chance. You can marry a seemingly perfect person and they can transform before your eyes into imperfection, or you can marry a flawed person and they can become someone you actually like, and therefore flawless. The key point being that, for better or for worse, no one remains the same. One marries for security, children, and, if one is lucky, companionship. Although,” Sherry laughed, “in Valentine Darsee’s case, good luck on the last.”

“I can’t believe Lady!” Alys said. “No one deserves a spittle spray. Actually, I take that back. Hammy probably does deserve it.”

Ten minutes later, Alys believed Darsee deserved it too. She’d gone to congratulate Fiede and was about to climb down off the stage when she heard Bungles’s and Darsee’s voices. Their backs were turned to her and, despite knowing it was a bad idea to eavesdrop, Alys bent down to fiddle with her shoe.

“Reader’s Digest?” Darsee was saying. “Good Housekeeping? She is neither smart nor good-looking enough for me, my friend.”

“I read Reader’s Digest,” Bungles said, laughing.

“Yes,” Darsee said, “sadly, I know.”

“You have impossible standards in everything,” Bungles said. “Alysba Binat is perfectly attractive. But you’ve got to admit, Val, her elder sister is gorgeous.”

“She is good-looking. But, please, stop foisting stupid, average-looking women on me.”