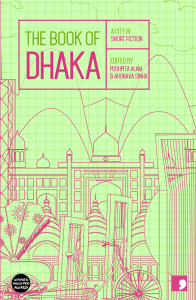

The Book of Dhaka: A City in Short Fiction

Edited by: Pushpita Alam and Arunava Sinha

|

|

Collections of place-themed fiction can be powerfully evocative with descriptions of indigenous sights and sounds, unique references to the geographical landscape, and above all, glimpses into the minds of local characters, who, with their attitudes, mindset, dialogues, dreams and desires represent the collective ethos of the place in the given time setting. Examples include Dubliners and The Red Carpet by Lavanya Sankaran which transport the readers to early twentieth century Dublin and Bangalore in the late nineties respectively. The Book of Dhaka aspires to add to this worthy genre. As K. Anis Ahmed mentions in the introduction, this collection of stories by various writers tries to capture the present-day ethos of the “world’s most densely populated city” of rice fields, lakes that overflow during the monsoon and “concrete structures, among roads far too narrow for anything to thrive but despair”. This intrinsic sense of despair hangs over the book, manifesting itself in the steam-of-consciousness monologue of a timid Chemistry lecturer who gets captured and tortured by the military in “The Raincoat” (written by Akhteruzzaman Elias and translated by Pushpita Alam), the story of a promising student whose poverty forces him to leave school and eventually become a gangster in “The Weapon” (written by Syed Manzoorul Islam and translated by Arunava Sinha) and that of a housemaid who resorts to peddling drugs in order to give her son a better future in “Mother” (written by Rashida Sultana and translated by Syeda Nur-E-Royhan).

The sense of gloom creeps like fog into the stories of the middle-class characters too. “The Decision” (written by Parvez Hossain and translated by Pushpita Alam) portrays the apathy of a young woman towards her ex-husband on coming across him at a book fair, as she rather indifferently contemplates on what went wrong in the relationship. “The Widening Gyre” (written by Wasi Ahmed and translated by Ahmed Ahsanuzzaman) is a chilling glimpse into the dangers lurking in the city roads where citizens are alleged to be shot dead in broad daylight. Among the most memorable of the lot is “The Circle” (written by Moinul Ahsan Saber and translated by Masrufa Ayesha Nusrat), about an overworked office man who is caught in the vicious cycle of a dull daily job, limited means and never-ending responsibilities, his love for his family curdling into a frustrated rage at his helplessness to do anything about the situation. Unlike him, the masseuse in “Home” (written by Shaheen Akhtar and translated by Arifa Ghani Rahman) braves her way through life, shrewdly and silently judging her clients even as she pursues her dream of buying a plot of land to make a home for herself and her young son. The surrealism in “Helal was on his Way to Meet Reshma” (written by Anwara Syed Haq and translated by Marzia Rahman), a story that begins brightly with a young man on his way to meet a potential girlfriend is likewise coloured not only by the blood of a suicide that he witnesses on the way but also with the frustration and disillusionment that seeps through the other characters. The fairy-tale-like denouement of a young lad’s good deed getting rewarded comes as a refreshing change in “The Princess and the Father” (written by Bipradash Barua), albeit darkened by the premise of the war and the pain of the members left behind in broken families. So too, does “The Path of Poribibi” (written by Salma Bani and translated by Mohammad Mahmudul Haque), another story that hovers on the edge of the surreal and the supernatural, and is easily one of the better stories in the collection. The reader is left with a set of unrelated, mostly dark images from the city, wondering whether the idea behind the collection was to indeed convey this very sense of bleakness. Indu Muralidharan | 2 May 2017 | Kitaab.org

|

Arunava Sinha

Arunava Sinha