Book Excerpts: Mr. and Mrs. Jinnah: The Marriage that Shook India by Sheela Reddy

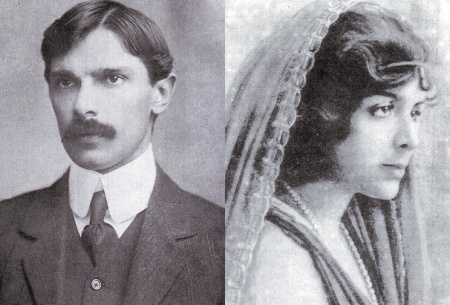

Mohammed Ali Jinnah & Ratanbai Petit in 1916 at Bombay

By the beginning of June, before the rains started to swell the rivers and make the roads impassable, all of Bombay’s rich and well-to-do returned home to their city in fashionable flocks; and with them returned the Petits and Jinnah, separately. Almost instantly, the strange and fascinating story of Jinnah’s and Ruttie’s romance began to do the rounds. Within a fortnight, even a stranger attending a public meeting in Bombay heard about their love story. After being introduced to Jinnah at a public meeting at the Bombay Presidency Association, Kanji Dwarkadas, then a young man of twenty-four, found out the gossip doing the rounds of the city on why the otherwise reserved Jinnah was currently in such unusually high spirits: ‘The reasons for Jinnah’s cheerfulness at the Association’s meeting — I found later. He had spent the two months of summer vacation in Darjeeling with Sir Dinshaw and Lady Dinbai Petit and there he fell in love with their 16-year-old beautiful daughter, Ruttie. As they returned to Bombay in early June, all Bombay heard of their impending marriage but the parents did not like the idea of their daughter marrying a Mohammedan. Ruttie was a minor but she was determined to marry Jinnah.

Kanji, like every other young man of his circle, had worshipped Ruttie from a distance since his student days. Walking on a cold afternoon two years ago across the Bombay Oval, he had caught sight of Ruttie riding in a small carriage driven by a pony. He could not take his eyes off the fourteen-year-old beauty, and watched the carriage and its occupant till they disappeared from sight. He never forgot her face, and discovered who she was from a photograph that appeared in a newspaper three months later. As for Jinnah, Kanji knew of him as a popular leader, without having ever seen him before. Which is why when Kanji saw a dashing man ‘in check trousers, black coat, hair parted on the side and moustache, addressing the meeting with great confidence and everybody listening with rapt attention’, Kanji turned to his neighbour to ask who this impressive figure was, earning the retort:

‘You don’t know Jinnah?’

Clearly, Sir Dinshaw’s snub had not cooled Jinnah’s ardour, which was again very unlike the Jinnah the world knew. He had never been known before to chase a woman, especially not one as young and enchanting as Ruttie, preferring to avoid them at the few parties he attended, where he hated the dancing and music, choosing instead to retreat to a quiet corner and engage any man who was interested in what was so far his only passion: politics. But now here he was, wherever Ruttie appeared — at the races, at parties and even the fashionable Willingdon Club where everyone went for the dancing and the live music—talking to her openly, oblivious to people’s looks and whispers. How much his persistence had to do with Ruttie was a matter of guesswork, because she now seemed to be doing all the chasing, going up to him and looking up at him with such open adoration that it would have been beyond even Jinnah’s iron will to resist her had he wanted to. They became the talking point of all Bombay — he for having the audacity to stand up to her father and she for her forwardness. In hindsight, it was hardly surprising that fashionable Bombay was so excited about what could, after all, have fizzled out as a mere teenage crush. But Bombay wanted their love to be something more than a passing fancy.

***

Rarely were her invitations turned down. They looked forward to meeting Jinnah in his own home but it was she who dazzled them. Jinnah was adored no doubt, but they could always meet him in his chamber where they were welcome at any time. But an invitation to South Court meant spending a few hours in the company of Mrs Jinnah. For the young men especially, who came singly, even those few who were married, Ruttie was a source of the utmost fascination. They were mesmerized, not just by her beauty and style and charming informality but because they had never before come across a young and beautiful woman from the highest society who could stay awake all night discussing politics with them in a haze of cigarette smoke and alcohol. All of them went away a little in love with her, and at least one of them—Kanji Dwarkadass—was enthralled for life.

Rarely were her invitations turned down. They looked forward to meeting Jinnah in his own home but it was she who dazzled them. Jinnah was adored no doubt, but they could always meet him in his chamber where they were welcome at any time. But an invitation to South Court meant spending a few hours in the company of Mrs Jinnah. For the young men especially, who came singly, even those few who were married, Ruttie was a source of the utmost fascination. They were mesmerized, not just by her beauty and style and charming informality but because they had never before come across a young and beautiful woman from the highest society who could stay awake all night discussing politics with them in a haze of cigarette smoke and alcohol. All of them went away a little in love with her, and at least one of them—Kanji Dwarkadass—was enthralled for life.

But she had eyes for no one other than Jinnah. To see him as he sat there—at his relaxed best, stretching out his long legs as he made a telling point; to catch him in one of those rare moods when he talked in a personal way, hearing him recount anecdotes from the past with his dry, sharp wit and dramatic flair, to listen with everyone else, with the same rapt attention, as he held forth on politics, demonstrating his quick grasp of political intricacies—was to fall in love again with the J she used to know before her marriage. And they both were at their best at these small gatherings—she, because she never felt so cherished by him than when he included her in his political plans, listening to her in all seriousness and good-humouredly taking the way she teased and pulled his leg in front of their guests. It gave her a secret sense of her own power over him, able to say aloud to him all the irreverent things that no one had dared to say to him before. The young men certainly were awestruck by the liberties she took with the great man famed for his haughtiness and reserve. And Jinnah too blossomed under her adoring attention, with his conversations at the dinner table becoming a virtuoso performance. She was seldom so happy as when there were one or two friends present and she could show how happily married they were.

***

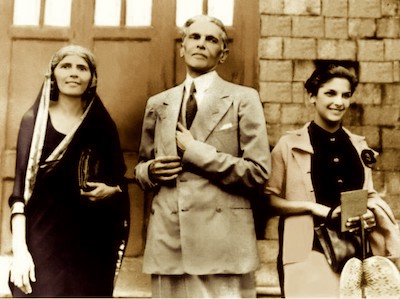

Quaid with Fatima Jinnah (Sister) and Dina Jinnah (Daughter)

But in truth it had not occurred to Jinnah to be ashamed of anything Ruttie did, and certainly not where her clothes were concerned. He trusted her judgement on aesthetic matters so implicitly that he had even surrendered himself into her hands for a thorough makeover. She not only insisted on him getting a sleek new haircut, but also got rid of the woollen suits with the stiff collars and cravat that was still the trend, especially in the older generation. She picked out new jackets for him, made of light silk and worn open-necked without the constricting bow tie, which suited his slim, graceful form to perfection. It was a subtle change she worked on him, understanding his need to impress as well as escape the contempt of the British by outdoing them in sartorial elegance. It ended up lending him a new air of easy and graceful informality, much admired by British and Indians alike. ‘Nobody knew how much Jinnah owed in this matter to Ruttie,’ as Kanji was to write later.

Her own style, however, sprang from a different way of looking at the world. With her upbringing and self-assurance, she had none of his need to impress. She dressed as the new generation in England was learning to dress—‘creating ever new and fantastic styles and imagery of their own with which to astonish the world and amuse themselves’. In her own circle, it was a style much admired, making her ‘the daintiest, naughtiest, darlingest of the swish set, smarter than them all’. But it did not go down so well in the eyes of Jinnah’s conservative circle of acquaintances, both British and Indian.

She had evolved by now her own unique style, combining Indian dress with the latest fashion from England, producing an effect so striking and aesthetic that nearly everyone in her previous circle of friends and female acquaintances had tried to copy her clothes. But it was a difficult style to imitate, needing a sense of immense self assurance to carry it off. Her saris were no different from what every fashionable Indian girl of her age wore or at least coveted—gossamer thin gauze in rainbow hues. The fabric was even more transparent than what women of Lady Petit’s generation wore at the beginning of the new century—diaphanous chiffons and georgettes with intricately embroidered borders stitched on to it.

Although Ruttie would have hated to admit it, her style was, in fact, an extension of her mother’s taste, rather than a departure from it. Both were discriminating in what they wore, shunning loud colours and anything elaborate or fussy. Rutty had an even more refined horror of anything flashy, especially gold zari work. And for this reason, she refused to buy anything off the shelves, believing that it was only possible to get the right sari by ordering it from the traders who came home with their tin trunks. She was prepared to wait for months for the sari to be specially woven for her in the plain, pastel colours she preferred, ‘without vulgar tinsel marring it’.

***

However, the English memsahibs were not the only ones to be shocked at Ruttie’s daring dress. She created even more ripples among the conservative Muslims who considered her way of dressing as that of a ‘fast woman’. Especially provoked were the ‘bearded Moulvies and Maulanas’ who formed an important part of Jinnah’s political world. Chagla recounts an incident at Globe Theatre where a Muslim League conference was being held. When Ruttie walked in and took her seat on the platform meant for VIPs, Chagla writes: ‘The hall was full of bearded Moulvies and Maulanas and they came to me in great indignation, and asked me who that woman was. They demanded that she should be asked to leave, as the clothes she flaunted constituted an offence to Islamic eyes.’

But instead of toning down her dress, Ruttie seemed to take a mischievous pleasure in provoking people further. Barely a month into her marriage, she made a dramatic entry into the Viceregal Lodge in Simla wearing her usual short, sleeveless choli under a transparent sari. Far from being intimidated by the disapproving stares, she took further liberties by refusing to curtsey to the viceroy, according to the protocol. Instead, she folded her hands in the Indian custom after shaking hands with him. Lord Chelmsford did not let the insult go unremarked. ‘Immediately after dinner the A.D.C. asked Ruttie to come and talk to the Viceroy. Lord Chelmsford pompously told her: “Mrs Jinnah, your husband has a great political future, you must not spoil it . . . In Rome you must do as the Romans do.” Mrs Jinnah’s immediate retort was: “That is exactly what I did, Your Excellency. In India, I greeted you in the Indian way.”’ According to Aziz Beg, author of Jinnah and His Times, ‘That was the first and the last time she met Lord Chelmsford.’

***

It was eventually the governor’s wife, Lady Willingdon, who belled the cat, so to speak. ‘The story,’ as Jinnah’s biographer Hector Bolitho writes, ‘is that Mrs Jinnah wore a low-cut dress that did not please her hostess. While they were seated at the dining table, Lady Willingdon asked an ADC to bring a wrap for Mrs Jinnah, in case she felt cold.’

Jinnah’s response was characteristic: ‘He is said to have risen and said, “When Mrs Jinnah feels cold, she will say so, and ask for a wrap herself.” Then he led his wife from the dining room, and from that time, refused to go to Government House again.’

***

At the end of December 1919, Jinnah and Ruttie took their first trip out of Bombay since arriving with the baby. Leaving it behind with the nurse and nanny, they left to attend the year-end sessions of the Congress and the Muslim League in Amritsar. It had been only three years ago when a sixteen-year-old Ruttie had set out on a train with her aunt to attend her first Congress session, filled with excitement at the prospect of listening to three days of long speeches. But that wide-eyed excitement had long since died and now it was all as dull as she had feared it would be.

Amritsar was rainy and cold and depressing, and there was thin attendance at the sessions of the Muslim League, with the opening day going only into reading aloud the presidential address which stretched for several unbearable hours. Then, midway through the session, the Ali brothers entered and took over the stage and the hearts of the audience and the air was rent with cries of “Allahu Akbar” and loud weeping. It was a scene that appealed to neither of them.

The Congress sessions which took place simultaneously were equally tedious, with leaders spending hours debating over a single amendment to a resolution. Like her youthful self, the days of stirring political speeches that had so fired her up with patriotic zeal seemed to have suddenly ended. She felt burnt out.

The only thing she could think of that might help lift her sinking spirits was to plan a trip alone to visit Padmaja (Naidu) in Hyderabad, leaving both Jinnah and the baby at home.

It was a city that she had never visited before, except for the aborted trip she made with Jinnah the previous April when they were forced to take the next train back because the Nizam’s government objected to a speech he made there and banned his entry into the state henceforth.

She had always longed to go there, especially after she got to know Sarojini and her daughters. As a girl, Padmaja’s description of the life they led there, the impromptu parties and picnics and fetes and the warm friendships, with people visiting each other for breakfast and midnight music sessions, had made a deep impression on her, and now, being the social outcast she was in Bombay, she yearned to become part of this charmed social circle where no one ever seemed lonely or depressed.

“Hyderabad, it seems, could quite well give Bombay a lesson on ‘How to make things hum a bit,’” she had written wistfully to Padmaja at fifteen, when she was convalescing in the Petits’ monsoon retreat in Poona. And to Leilamani a year later, imagining a city of romantic charm: “of beautiful Begums and warrior Nawabs, of fragrant white jasmine and passionate burning incense sticks, of luxurious diwans and rainbow coloured sticks, of mosques and fortresses and muezzin cries, of throned elephants and oriental pomp”.

Except for the short trip she had made to Mussoorie to visit them in their boarding school shortly after her marriage and an equally short visit Padmaja made to Bombay just before her mother’s departure for England, Ruttie had not spent any time with either of the Naidu girls for the past two years. Caught up as she was in her new life, even the correspondence between them had stopped, with not a single letter exchanged between them since her marriage. She longed to get close to them again and spend at least a fortnight with them in their home when they could once again tell each other their secrets, and she would no longer feel so lonesome.

Not the least of its attractions was, of course, that it would give her the break that she badly needed, both from Jinnah and the baby. With the ban order against him, Hyderabad was the one place he could not possibly propose joining her. It was to be her bachelor trip, without him or the baby to hamper her, free to bond with her girlfriends.

Sarojini was still in England, convalescing from the surgery she had undergone, but both her girls were in Hyderabad with their father, with the younger one, Leilamani, having just finished school. They greeted her plans to visit with a warmth and enthusiasm that made her even more determined to go, although it left Jinnah less than enthusiastic.

Jinnah, of course, would have felt it beneath his dignity to argue with her, and it was only after she had actually left that he sunk his pride and began “writing and begging her to return”, as Padmaja wrote to her brother, Ranadheera, during Ruttie’s visit. Hurt he must have surely been, given his “over tuned senses”, as Ruttie termed that hypersensitivity he hid behind his impassive exterior.

For her to abandon him like that, when she knew very well that he could not enter Hyderabad because of the Nizam’s order, probably cut him to the core.

But more important, it would have triggered that conflict between his old and new selves that he had begun feeling ever since his marriage – the urbane gentleman of liberal ideas at war with his father’s son. It was not the first time – and certainly not the last – when he would have realised the abyss between them – he, born of a mother who had never once gone anywhere without her husband; in fact, her devotion to his father was so total that she even refused to stay a while longer in the village during Jinnah’s first wedding because her husband was going back to the city and she could not bear him going without her.

While here was Ruttie, from such a different world, setting out on a pleasure trip without him, as if it was the most natural thing to do – as indeed, it was, having seen her mother and her set living in a world quite apart from their husbands. But still, whatever his feelings might have been, he kept them stoically to himself, saying nothing while she made her own plans.

Funnily enough, neither of them seemed overly concerned about her leaving the baby behind, although it was only five months old. Having installed her from the day they returned from London in her own nursery, they seemed to have almost forgotten her existence. It would take at least another year before Ruttie’s unnatural lack of attachment to her baby would attract comment, but even in these early months there was less than the usual weak connection that seemed to exist between infants in well-born modern households and their otherwise busy parents.

So little did either of them involve themselves in the baby that it had not even occurred to either of them that she would soon require at least a name of her own.

It was a puzzle why Ruttie, of all women, who even as a child could not bear to see a suffering creature without rushing to its aid, turned her face away so resolutely from her own infant daughter. Could it be perhaps her resentment, hidden so far under her guise of careless insouciance, but chafing nevertheless at this “slavery”, as she later put it – this double bondage of wife and mother that she had not bargained for in her passionate eagerness for life, not yet daring to spill out into open rebellion, but still unable to resist her heart’s stifled cry of “Let me be free. Let me be free”?

Panicked suddenly that “her youth is going and she must live”, that “life is passing her by”, she was determined to try and recover her old self, “longing to be free of all her shackles”. She needed some time alone with her friends, to immerse herself once again in the old life that she had so foolhardily turned her back on. Of her family, Lady Petit, at least, was eager to make up with her daughter, yearning to see her little granddaughter but Ruttie, with a pride as stubborn as Jinnah’s, wanted to have nothing to do with her, turning instead to her friends in Hyderabad as if they were her one and only family.

But while it was easy, even imperative, to leave behind both Jinnah and the baby, Arlette, her precious dog, had to go with her because she could not bear to part from her, even for a fortnight. And although the Naidus’ home was already overcrowded with a menagerie of pets, including several dogs, cats, a squirrel, deer and a mongoose, she insisted on not just taking Arlette along but its attendant as well and the boxes of its special food, watched mutely by Jinnah, his face giving away nothing as she set out on her first holiday without him.