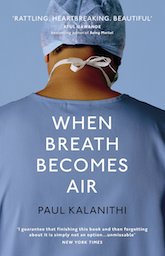

When Breath Becomes Air

Paul Kalanithi

|

This book, already a bestseller in the United States, opens with a trainee surgeon examining a set of images from a CT scan. His highly trained eye takes in how the tumours are dispersed across the lungs, how the spine is deformed, how one lobe of the liver has been obliterated. The diagnosis is straightforward: “Cancer, widely disseminated.” Only one thing makes this case different from the dozens he deals with each week: these are scans of his own body.

The doctor in question was Paul Kalanithi, who discovered he had inoperable lung cancer at the age of 36. The cliche about someone having everything to live for could have been formulated for him: he was on the verge of qualifying as a neurosurgeon after a decade of training, and was planning to start a family with his wife, Lucy. Instead, he found himself confronting not only a terminal illness, but also a profound identity crisis: having aspired to be “the pastoral figure … I found myself the sheep, lost and confused”. This account of his transition from doctor to patient was written in the year or so prior to his death early last year, by which time he was 37 and his daughter, Cady, was nine months old. Prior to his illness, Kalanithi’s life had been one of relentless striving and exceptional achievement. A doctor’s son in the Arizona desert town of Kingman, he was given a place at Stanford University and went on to complete a postgraduate degree in English literature. But his scientific interests did not fit comfortably into an English department (his thesis was on “the medicalisation of personality” in the work of the poet Walt Whitman), and, besides, he was tired of sitting around reflecting on the meaning of life – he wanted action, real responsibility, “answers that are not in books”. So he enrolled in medical school. Advertisement For Kalanithi, medicine was never just a job, it was another approach to the metaphysical questions he had taken aim at during his English degree. In his fourth year he was puzzled when many of his contemporaries decided to specialise in areas, such as radiology or dermatology, which promised humane hours, high salaries and only moderate pressure. Of such “egotistical” concerns, he tartly observes: “Putting lifestyle first is how you find a job – not a calling.” (I wondered at this point whether, had he worked in England, he would have joined the striking junior doctors, but despite his interest in ethics he doesn’t venture anywhere near the grubbier business of health policy). He chose neurosurgery, the most difficult specialism of all, drawn by its “unforgiving call to perfection”. The demands of the training are almost unimaginable: he worked more than 100 hours a week, doing operations in which the difference between life, death and worse could be a matter of millimetres. Late one night, as he cuts into a tumour deep inside a patient’s brain, his supervisor asks him what would happen if he increased the incision by two millimetres. Double vision, guesses Kalanithi. “Locked-in syndrome”, comes the reply. The least interesting part of When Breath Becomes Air is the section on neurosurgery, which suffers by comparison with Henry Marsh’s wonderful memoir Do No Harm. While Marsh applied the same intelligent detachment to his own ego and insecurities as he did to the cases on his operating table, Kalanithi – at least in his incarnation as a doctor – doesn’t go in for self-reflection or humility. I longed for him to dig a little deeper into what motivated his drive for perfection, even when it came at the expense of his own health and almost destroyed his marriage, but his achievements are simply presented like so many trophies lined up on the mantelpiece. Even the couples counsellor he and Lucy go to in the wake of his diagnosis, we are told, sees only excellence: “You two are coping with this better than any couple I’ve seen … I’m not sure I have any advice for you.” But as cancer weakens Kalanithi’s body, forcing him to abandon his heroic self-image, his writing gathers strength. The odd limbo period in which he is increasingly sure that something is wrong, but hasn’t yet had the tests to confirm it, is rendered in horrible detail. Despite being plagued by terrible back pain, with his weight dropping fast, his wife only finds out about his fears when she picks up his phone and finds “frequency of cancers in 30- to 40-year-olds” typed into a medical search engine. Even then he continues to work, dosing himself up on Ibuprofen and putting in 36 hours at the operating table only days before his diagnosis. But then, what else can he do? Beckett’s line comes back to him from his literature days: “I can’t go on … I’ll go on.” Receiving the diagnosis changes everything and nothing: “Before my cancer was diagnosed, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. After the diagnosis, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when.” Kalanithi’s first instinct on discovering he has cancer is to obsess about statistics and survival curves – after all, he knows only too well where to look them up. A planner by nature (he had a 40-year career plan), he wants to know how long he has: if it is three months, he will spend time with his family; one year, and he will write a book; 10, and he will go back to medicine. But he finds that averages and probabilities, while useful to a doctor in deciding between treatments, have little meaning for a patient. “What patients seek is not scientific knowledge that doctors hide, but existential authenticity each person must find on her own … the angst of facing mortality has no remedy in probability.” In the absence of any certainty, he decides that all he can do is assume he is going to live a long time. Once the drugs kick in and the symptoms subside, he puts on his scrubs and heads back to the operating theatre, and he and Lucy embark on a course of IVF. “Don’t you think saying goodbye to your child will make your death more painful?” asks Lucy. Kalanithi responds: “Wouldn’t it be great if it did?” Any healthy person deciding to have a child might of course ask themselves that question, and come up with the same response. The power of this book lies in its eloquent insistence that we are all confronting our mortality every day, whether we know it or not. The real question we face, Kalanithi writes, is not how long, but rather how, we will live – and the answer does not appear in any medical textbook. It brings him back, at last, to the books of poetry he left gathering dust when he entered medical school. |