The Reluctant Feminists

Ayesha Siddiqa

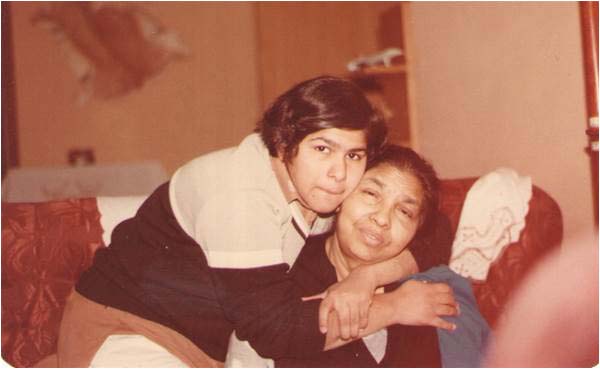

My Mother and I (Ayesha Siddiqa and Jamila Hashmi)

How does one recognise a feminist? Is it by how aggressively she demands equal rights? Is it by challenging traditional roles ascribed to a woman and restructuring her personal space? Or is it someone who wears her feminism on her sleeve all the time? I guess I never seriously thought about feminism while I was growing up, maybe because I never had to. Having spent my life in Lahore with two feminists who were different from each other in their approach to feminism yet similar in their perception of tradition, contesting for their space as matriarchs in a highly male oriented society, feminism was always in my bloodstream. This is a reference to a life spent with my mother, the Urdu novelist and short story writer Jamila Hashmi and her good friend and poetess Kishwar Naheed. It’s through these two women in particular, and a few more, I learnt that feminism couldn’t be drawn in a straight line. It is better defined through its inner contradictions and along a winding trajectory that life itself is.

For their friends and circle of intellectuals the two women were diametrically opposite. And different they were indeed. My narrative weaves together their differences and inner contradictions to explore the deeply feminist psyche of both, a desire to capture and claim their own space and define their relationship with society and the world on their own terms.

At the risk of using a much-beaten-to-death cliché, a lot of those claiming to be liberal-feminists in Pakistan may consider Jamila Hashmi as an anti-thesis of both liberalism and feminism. She visibly appeared a conservative – a woman who regularly prayed five times a day and organized milad before celebrating her only child’s birthday party. What’s worse, she opted to accept her mother’s choice to marry a man who was already married, had a grown up daughter and was a sajjada nasheen of the Khanqah of Mohkum din Sairani in Bahawalpur. This is a woman, who by the time she got married in the late 1950s had already published a novelette Atish-e-Rafta depicting the culture of East Punjab which is recognized by her contemporaries and other critics of Urdu literature as a mini classic. She was also formally more educated than her husband. Jamila Hasmi did her masters in English Literature from FC College, Lahore where she was taught by some very capable American professors. Yet it was almost a surrender of the kind we see in vintage Hindi films when asked to take a peek at her husband after the nikah her response was, “Does it matter now?” Later, she went to live in a village where there was no electricity in the first few years of her marriage.

Soon after marriage she was asked to select her duty, she was asked if she wanted to take care of the washing and ironing of the husband’s clothes and his food or take care of the langar (daily feast cooked for visitors to the shrine). Being a city girl she couldn’t care less for the latter and so opted to take care of the husband while the co-wife, who was more conscious of the political economy of the place was all too happy to go for the more lucrative deal. Controlling the langar gave access to extra finances and established power vis-a-vis the khalifas of the pir. It translated into greater influence than what the husband’s dirty laundry could. The tension between the two wives was always of a political nature and played out silently. When in Bahawalpur, they would have their evening cup of tea together which was a moment for friendly banter, family gossip and sometimes a discussion of the man they shared between them. My mother was conscious of the decision she had made, due to what she explained to me later was an absence of options. Her first choice was not to get married at all but if the choice was depending on the whims of her brothers and their wives and having a life of her own then she opted to get married. For her waiting for the right man didn’t seem to be an option. Nor did she have the choice to compete with her husband’s first wife, who never felt seriously threatened by the younger co-wife. The senior wife had agreed to let her husband marry a second time for she had not been able to produce a son who would inherit the mantle of the sajjada nasheen. She knew that her husband would get married again; the choice was between letting larger politics ruin her and her daughter’s life, and a lesser evil. Her daughter’s mother-in-law was eyeing my father for her own daughter. Being the older family in the lineage of pirs of Owaisi silisila, the pressure from the pirs of Khankah Abdulkhaliq in Chishtian might have prevailed had my stepmother not encouraged my father to look outside the clan. In any case, in the State of Bahawalpur of those days it was fashionable amongst the Nawab and notable families to marry Punjabi women.

But the formally educated woman had no inkling of the deeper politics of the place. She didn’t know she had to watch her back all the time amidst people who otherwise spoke softly in a dialect considered as one of the sweetest languages of the subcontinent. Jamila Hashmi gave birth to a healthy son who was then killed through deceit and conspiracy. She bore the pain stoically. However, she also planned more carefully not to bear the second child, a few years later, in Bahawalpur. Thus, I was born safely in a hospital in Lahore. Many years later when the story of what happened to my brother was revealed to me including the identity of those involved in the crime I wanted to know how she could still talk to those people. Her answer was, “It’s up to God to take my revenge.”

Was this the archetype of a true believer? Perhaps yes but her decision was also based on a deeper strategy to survive because there wasn’t much she could do in the face of family politics in which the odds were against her. I saw her great survival instinct at work again after my father’s death in 1979 when the family wanted her to leave, or face piles of court cases. Had it not been for her inner resolve and friends like Barrister Ijaz Hussain Batalvi, Jamila Hashmi the writer might not have survived. And her God was certainly with her during those tough times – God whom she remembered while saying her prayers and singing bhajans of Jotika Roy and Mira Bai. I had once asked her if she considered her bhajan singing as a contradiction of her faith as a Muslim. She just smiled and reminded me there were several ways of remembering the Almighty.

But referring to her personal struggle there was no way she was ready to accept that her husband’s clan dictate terms to her. To date the ordinary folk of village Khankah Sharif often refer to her as a shairnee (lioness) who not only fought for herself but for others too. She was the ultimate matriarch who negotiated the rules of life on her terms even though the path may sometimes have looked long and arduous. I once asked her why she named me Ayesha Siddiqa when most of my class fellows at school had normal surnames. “It is because I don’t want you to keep changing names from one house to the other. What’s the fun of changing from your father’s name to your husband’s? I want you to have your own name and a personality to go with it if possible” was her quick response that I understood many years later much after I had experimented on my own with changing names.

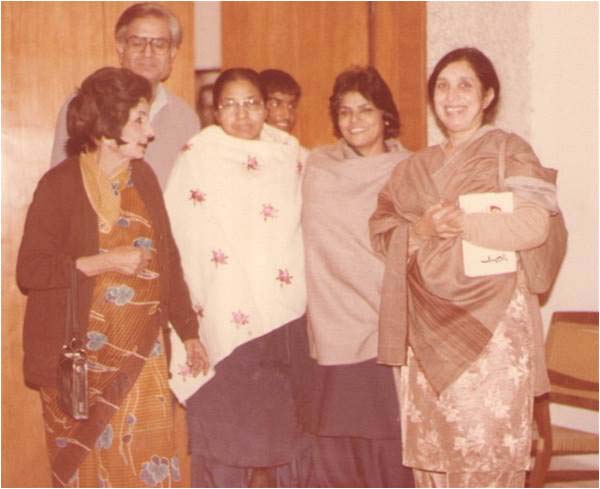

Left to right Hijab Imtiaz Ali, Masood Ashar, Jamila Hashmi, Kishwar Naheed and Nisar Aziz

The sanctity of a name was critical in her scheme of things. Ironically, she was Jamila Hashmi in her own world but would conveniently switch to Begum Sardar Ahmed Owaisi when she was in my father’s world. She continued with this even after his death. It was both out of love and a sense of pragmatism that she conceded space and not fight for every inch as perhaps the feminism theorists would have expected her to do. Her logic was that this was not subservience but an expression of love and gratitude for someone who had expanded her canvas. She had an independent life as a creative writer in which my father always assisted her silently. He would, for instance, make sure she had everything available for her annual shab-e-afsana events. She organized a story telling night once every year in winters where a select number of writers were invited to write and read out a new story. People ranging from Ashfaq Ahmed, Bano Qudsia, Qudratullah Shahab to Intizar Hussan, Hijab Imtiaz Ali Taj, Nisar Aziz, Salahuddin Mehmud and many others became a part of her shab-e-afsana at one time or the other. Those were indeed great days of literary life in Lahore when people used to meet to discuss new works and organised themselves in groups known less for ideology and more for an ability to sit together and share thoughts. The divide between different groups was often very sharp but these meetings were a great source of learning as there was such exhibition of wit, intellect and even humour. This was all my mother’s world in which she never forced my father to participate. In fact, she was happy to keep the worlds separate so her husband might not feel threatened. Her explanation was that she wanted him to be the center of attention and that was not possible amongst her bunch of friends who were absorbed in their own worlds. But I believe this was also her way of securing her own space without creating tension between her multiple lives.

The fact that she was deeply feminist came out very visibly in her fiction. Be it the novelette Atish-e-Rafta on East Punjab; Rohi on the phenomenal Cholistan desert; Chehra-ba-Chehra Rubaru on Sufism of a Bahai rebel poetess, or Dasht-e-Soos on the life of the renowned Sufi Saint Mansoor Hallaj, and her numerous short stories, her protagonist was always a woman. Sadly, she is one of those post-1947 Urdu fiction writers who contributed tremendously to its literature but have not received attention due to the politics of the language. (Most literary critics, who are ethnic Urdu speakers or writers of the same ethnicity tend to limit themselves to either their own work or that before partition. For example, Intizaar Hussain’s appreciation of Urdu literature ends before 1947 or extends to his own work or that of Quratulain Haider’s). Also, given the dearth of works translated into English very few have access to some of the rich literature produced by non-Urdu speaking writers. Jamila Hashmi, for instance did a lot of experimentation in both style and content. The last two of her works are related to Sufism and Sufi philosophy, which I also consider as great examples of her feminism. Chehra-Bachehra Rubaru is about the Bahai poetess and Sufi Quratulain Tahira who abandoned her home and hearth in search of eternal love. Her desire to meet the Bahai religious icon Mullah Muhammad Bab, whom she had never met ‘chahra-bachahra rubaru’ (face to face) keeps the fire within alive. It also kindles a greater fire of eternal love in her heart. At one level Quratulain Tahira brings out all the rebellion that Jamila Hashmi might have wanted to participate in herself.

One would imagine that the main player of her novel she wrote in the mid-1980s on Mansor Hallaj would be Hallaj. However, throughout the story you cannot escape the overbearing aroma of Aghul Ghaimish, the woman that Hallaj only saw once and fell in love with. They never met but her desire was the flame that built inside him into a bigger fire and consumed him completely. It’s then that Aghul merges with God who then extends into Hallaj forcing him to utter “anal Haq” (I am the ultimate truth, I am God). This was an unexpected love story or at least with an unusual ending. I vividly remember one Lahori poet and friend of my mother’s asking her if the novel had any romance, to which she sheepishly replied in an affirmative. The gent eagerly borrowed the first copy off the press to return it quickly three days later. He was visibly disappointed to see it was not the kind of romance he expected nor was it the usual run of the mill novel. It has a very poetic and unusual diction that one doesn’t come across in Urdu fiction. Others from the liberal left were equally agitated as had they expected a story that would bring out Hallaj – the messiah of the poor – as he was commonly imagined. But Jamila Hashmi had done a lot of historical and theoretical research to write about the Sufi saint’s inner journey. He may have been a messiah to the dispossessed or someone who challenged the status-quo of religion in 9th century Baghdad. But Hashmi’s interest was in writing about the journey, which started with Aghul Ghaimish and ended with every bit of Hallaj’s body, as it was hung by the King’s decree and then chopped into pieces, screaming anal Haq.

Jamila Hashmi was unwilling to confine a character to a certain stereotype. She wouldn’t do that even with her own feminism, which definitely came on tiptoe.

Unlike Jamila Hashmi, Kishwar Naheed’s feminism came in bright colors and was audible even from miles away. She comes out as a woman passionately advocating empowerment of the female. Now that Kishwar Naheed, whom I call Maasi is in her 70s, one can sometimes only see traces of the vivacious and rebellious young woman she was during the 1970s. The Pakistani society, especially the intellectual circle in Lahore, was liberal and it was fashionable to claim to be left of center (some prominent female writers even used the movement to find right husbands). Kishwar Naheed of those days was known less for her poetry and more for her brazenly bold persona. She was also quite sought after due to her position of director Pakistan National Centre Lahore. Those were the days when writers were not as affluent as they later became under Zia’s regime. Poets and fiction writers took pride in their ideology and had a lot of darveshi in them. Most intellectuals would gather in the evening at Pak Tea House or those who could afford it used to go to Shezan at the Diyal Singh mansion on The Mall, Lahore. During the day, Kishwar Maasi’s office in the Alfalah building was a much sought after place for all. It was fascinating to see her conduct the business of her office efficiently while entertaining her visitors at the same time. She was a tough taskmaster and not a boss to be toyed around with. Later, she was made editor of the official literary magazine Mahe Nau. Her last position in Lahore was as the Director-General of the Urdu Science Board to which she was appointed by the first Benazir Bhutto government. Her appointment to the Board created a lot of consternation amongst the Ashfaq Ahmed-Bano Qudsia gang because up until then Ashfaq Ahmed was of the view that the military dictator Ziaul Haq had appointed him DG for life. Kishwar Maasi confronted this opposition and propaganda most gracefully like a real dervish while Ashfaq Ahmed filled with anger could not even be the shadow of the Sufi he so pretended to be.

The literary scene in the country, which was dominated by Lahore, comprised of gangs or prominent individuals. Even the ideologically oriented groups were structured around personalities. For instance, there were the Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Wazir Agha, Ashfaq-Bano-Qudratullah Shahab-Mumtaz Mufti and Faiz Ahmed Faiz groups, among a few others. The more liberal and socioeconomically mobile used to congregate around Faiz sahib. There were times when inter-group battles akin to gang warfare would take place (all verbal). There were also personalities beyond politics like Sufi Ghulam Mustafa. Tabassum. I would place my own mother and Kishwar Maasi in the last category. In fact, Maasi Kishwar could have made a gang of her own since she was very social. Her house, initially in Krishan Nagar and later Allama Iqbal Town, Lahore was a center of activity almost every evening. She would return from work and cook for herself and husband and poet Yusuf Kamran, and their two sons Moazzam and Faisal. But there were always plenty of guests. She used to host great dinner parties and would really go out of her way to take care of people. There were those like Zahid Dar who were fascinated by her and would come to her house every evening as if they would to the astaana of a pir. Then there were others, who would benefit from her hospitality yet talk behind her back.

Dar was not the only one fascinated by her. There were youngsters like me who were overawed by her glamour. She was certainly the saviour every year on my birthday when she would come to temporarily rescue me and my friends from the milad party my mother organized. It was unimaginable to think of her joining a religious event. She would silently open the door of the room where milad was happening and gesture to me and my friends to come out. What a happy moment it would be for me, short lived though, as we would soon bump into my mother who would stare at Kishwar Maasi and protest Kishwar tu mera milad na kharab karya ker (Kishwar don’t ruin my milad) and take us back into the room. However, she would do her spoiling act every year and would get invited by my mother without fail. As mentioned earlier, the two women were very different from each other yet very good personal friends. Their relationship certainly did not depend on shared ideologies or views but loyalty towards each other that was passed on to me after my mother’s death in 1988. Indeed Maasi is one of the few people from amongst my mother’s friends who accompanied me twice to Bahawalpur to bury my parents.

Referring to my fascination with her you can imagine the excitement when she once landed at our house to stay there for three days. She had some issue with her husband so had left her house to be at ours. Later, her husband and in-laws came to negotiate her return. Perhaps, people around would take this aforementioned incident as something that was normal in those days but it is obvious that there were limits to the freedoms of even a feminist. Though one should certainly not take this incident as reflecting on the personality of Kishwar Naheed whom Ahmed Bashir referred to as chappan churi or about whom others said, Kishwar toN tey biwiyaaN nooN parda karwana chahhida hey (wives should be hidden from Kishwar). Indeed, she had two worlds (or maybe more) – the one that people so talked about was the only one they could see, then there was the other that I had a chance to meet sometimes, if not too often, and which I found equally strange.

I was in my early teens that I had my first chance to meet the other Kishwar Naheed. This was early 1980s and writers from all over Pakistan were invited to the Writer’s Conference by Ziaul Haq’s Academy of Letters in Islamabad. Since my mother had no one at home to leave me with she had no option but to take me along. The only problem being that they couldn’t find me a seat in the same airplane to Islamabad as my mother. I finally got a seat in the next flight with Kishwar Maasi who was asked to bring me along. Perhaps, my mother knew the other Kishwar, else why would she trust her with me? The reason I emphasize this is because the mutual trust wasn’t as obvious in ordinary days, especially when I was taken to dinner parties at Maasi’s house and made to sit in another room because the conversation in the main sitting area used to be free flowing. My mother’s gripe was that Kishwar doesn’t realize when not to say something in front of children (you can consider this my mother’s over-protection but also those were different times. Those were the days when you were told not to read D.H. Lawrence or Francoise Sagan until you were of age. Now people would consider the fiction of these writers as barely worth raising an eyebrow over). But going back to my journey to Islamabad, as we arrived at the Lahore airport, which was basically a big hall with kiosks spread around it and check-in counters in one corner and a small waiting area in front before you went into an equally small departure lounge, I insisted on buying a bottle of 7-Up. Not that I wanted the drink but was craving for an opportunity to go make the purchase from one of the kiosks myself, a novel thing for me. I remember the shock I felt when Maasi looked at me, made sure that I desperately wanted it, and then sat me in a secure corner before she trooped off to buy my the drink.

Maybe it was just an accident! But I met this Kishwar Naheed again many years later when my mother was long gone and my personal life was in turmoil. I had gone to ask her a simple question – whether a woman could live on her own and survive. After all, she was one person who had been living on her own since her husband’s death in the 1980s and especially since she moved to Islamabad. It took her seconds to fathom my problem but her response was, “Women go through a lot, even get physically abused to keep their houses together. Don’t think you can’t do it”. Was this the author of ‘Buri Aurat ki Katha’ talking to me? With this kind of answer it was natural for me to hide from her when proverbially the ‘shit hit the fan’ in my life. When we did eventually meet after a few days she repeated her advice. But when I convinced her that I had reached my threshold she stood by me like a solid rock. Yet the reaction of a lot of people who knew her, my mother and I was, “Surely Kishwar must have advised you to take the drastic step?” It was moments like these I knew they didn’t know my Kishwar Naheed who was not even her own ‘bad woman’. A few years later I introduced her to the person with whom I am now happily married but who was only a good friend at the time. I remember getting a phone call from Maasi that evening telling me sternly that ours was not a culture that would allow time for a man and woman to get to know each other. “Just get married” was her order. It is almost that I lived all my life with two Kishwar Naheeds – one who rebels for a woman’s independence, and the other, that willingly conforms to the abhorrent cultural norms of the society. But should we see this as an inner contradiction or a sign of social schizophrenia? Or is it that when Kishwar Naheed says:

“It is we sinful women

who come out raising the banner of truth

up against barricades of lies on the highways

who find stories of persecution piled on each threshold

who find that tongues which could speak have been severed”

It is less about empowerment and more about lamenting the plight of womanhood, which she is also a part of.

Indeed, the woman of her poems is a creature in pain as if she echoes the trauma of all injustice done to womankind by several generations of men sometimes as a father, a brother, a husband, a son or even a lover. Her characters certainly scream of the pain of being jilted. Yet Kishwar Naheed turned into a matriarch who has protected all colors and shape of men in her life and continues to do so. Intriguingly, she never evolved into the modern happy-go-lucky feminist who couldn’t care less about man-kind. Somewhere, the young girl who wants to be taken care of by strong hands and an embrace and thinks that life could be lived happily ever after, remains. No wonder, she got bruised more. But this is also why she is quick in informing the random hawwa ki beti, who happens to be close to her, how tough is the journey to empowerment.

“Inhey patharun pey chul ker agar a sako tu aawo,

Merey ghar key rastey mein koyee kehkashan nahee hey”

For both Jamila Hashmi and Kishwar Naheed, their paths were certainly not strewn with any galaxies. What they did, however, was to place the pebbles on the way, under their feet to reach their individual creative and personal universe. What I have learnt from these two women in my life is that no amount of theorising can explain feminism because it comes in varied shapes and forms. Let not your theoretical bias fail you in not recognising a feminist when you see one.