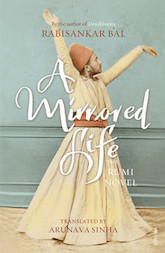

A Mirrored Life: The Rumi Novel

Rabisankar Bal

Translated (from the Bengali) by Arunava Sinha

Paperback: 224 pages

|

Bengali author Rabisankar Bal’s novel A Mirrored Life: The Rumi Novel, recently translated by the talented Arunava Sinha, tells you pretty early on to not pay too much attention to trifling things like memory, the truth behind stories, or even a writer’s fidelity. Authorship is simultaneously “a long journey of confronting questions” while not seeking accomplishment and “a short-lived attempt to hold on to memory”, we are told a few pages into this book that meanders from one beautiful sentence to another, and from one story to another, through the travels of its narrator Ibn Battuta, from Tangiers to China, over 30 years. Written in first person, the famous 14th century traveller-narrator expresses his wish to collect the manuscript of Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi’s masnavi (a collection of verses by the dervish that comprised 25,668 couplets and six volumes) from Konya, the city of the medieval poet, dead some 60 years when Battuta sets foot in that city. The novel begins, as any good travelogue must, with a description of the food of the city of Konya in Anatolia (now part of modern Turkey). The colourful marketplace scenes are described with relish, and one gets a taste of what is to follow—the narrator never meanders too far from Rumi, or the Maulana, as he refers to him in the novel. “Some of the principal themes of Maulana’s devotion and poetry are accompaniments to cooking. All that is raw must be made delicious and digestible through the process of cooking. The Lord will cook you with his own hands, for only then can he savour you.” This personal narrative is concerned with the role of writing. It asks a fundamental question—why write—and answers it by expanding on the role of memory that serves to not just pass on stories, but also as a channel of knowledge into the author himself. “You will understand as you write. You are the food, you are the one who eats, you are the cook,” Battuta is told by a “voice”. This self-knowledge alone leads to the knowledge of his subject, the narrator is convinced. However, this self-reflexivity isn’t extended to Rumi himself. We are expected to understand the narrator’s bias, and all critique of the central subject is eschewed in favour of swallowing his teachings whole. Battuta’s search for the manuscript leads him from the Futuwwa, an organization comprising Sufi monks, merchants and artisans in Konya, to the workshop of Yaqut al-Mustasimi, the city’s famous book-maker and calligraphist, on the outskirts of the city. Here, he hears more stories that continue in the vein of Rumi’s teachings about love. At the adabistan (the house of literature, as the workshop is called), Mustasimi promises to give him both, a manuscript and several evenings worth of stories that, as all good stories do, lead to even more tales. These stories are the Bagh–o-Bahar (or The Tale Of The Four Dervishes, first translated into English in the mid-1800s by Duncan Forbes, a professor of Oriental languages at King’s College, London) and segue into the life story of Rumi, “cooked” as he is in the love for Shamsuddin Tabrizi. The love story of Kira, Rumi’s wife, who is left behind after the Maulana senses the “lion of Tabrizi” approaching the city, is indicative of problematic narratives of love and passion, which aren’t as removed as we would like them to be from gender politics and unequal access to agency. No one—the writer, translator, narrator, or storyteller—questions the structures in place that allow for such an easy abandonment by the Maulana. But while the flourishes of love poetry may thrill those who wish for more “Rumi says”, one told by the narrator from his own travels lingered long after the book was read. In it, the narrator meets a horse-carriage driver, a young man of 24 years, and asks him his name. On hearing that it is one of Allah’s 99 names, and the driver isn’t aware of that, Battuta tells him to recite the namaz in a “middle voice”. “In life, the middle path is preferable, Mujib,” he tells him. The young man stares at Battuta, wondering what he’s going on about, and the narrator, fully aware that he’s coming across as preachy, is nevertheless unable to stop himself. “He had been born in Konya, and the Maulana had been born here too. Mujib had to bear the burden of history. His birthplace had given him the responsibility. A homeless man on a road to Espanha had once told me, history is not an event or a story, history is an obligation, which you are compelled to bear during your human existence.” Now, if only bhakts of various hues and colour understood this. Dhamini Ratnam | 21 March 2015 | Livemint

|

Rabisankar Bal

Rabisankar Bal