Book Excerpt: Britain Through Muslim Eyes by Claire Chambers

Introduction

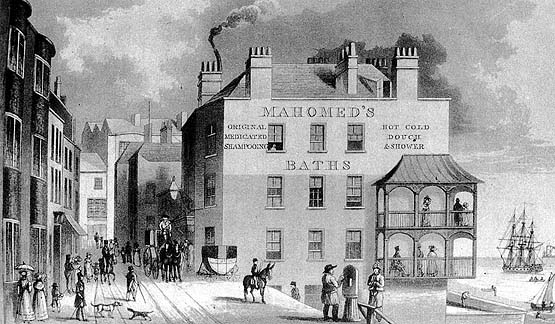

1826 – Print of Mahomed’s Baths in Brighton

In 1873, the King of Persia, Naser-ed-Din Shah Qajar (1831–1896), published a Safarnama, or travelogue, about his state tour of Europe.1 During the London leg of his journey, he writes:

To-day, before seeing the Ministers and others, the English Fire Brigade came, and in the garden at the back of our palace went through their exercise. They planted ladders, with the supposition that the upper floor of the palace was on fire; they mounted these ladders with perfect celerity and agility, and brought down people who were burnt, half-burnt, or unharmed, some taken up on their shoulders, and others let down by ropes made fast round their waists. They have invented a beautiful means of saving men. But, the wonder is in this, that on the one hand, they take such trouble and originate such appliances for the salvation of man from death, when, on the other hand, in the armouries, arsenals, and workshops of Woolwich, and of Krupp in Germany, they contrive fresh engines, such as cannons, muskets, projectiles, and similar things, for the quicker and more multitudinous slaughter of the human race. He whose invention destroys man more surely and expeditiously prides himself thereon, and obtains decorations of honour. (Redhouse, 1873: 190–1)

This quotation is emblematic of many of the concerns of this book and articulates preoccupations shared by several of its featured writers. The Shah exhibits his power and affluence by nonchalantly revealing that he is staying in a palace. He is clearly a well-connected man because soon after the firefighters’ visit he meets with British ministers. The Shah evinces simultaneous admiration and scepticism towards his British hosts.

They want to impress this royal visitor by demonstrating a fire safety routine. Having already seen Krupp’s armaments factory in Prussia and the Woolwich Armoury near London, the Shah is baffled by these Europeans’ sudden show of force for the preservation of human life. He expresses this in awestruck terms (‘the wonder is in this’), which, as we will see, are characteristic of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century travelogues. The Shah also inadvertently puts his finger on what Homi K. Bhabha has more recently called the ‘ambivalence’ of the colonial enterprise (2004): namely, that the murderous acquisition of empire is dressed up in the humanistic language of the civilizing mission. The Shah shows the British something new about their country because of his alertness to double standards and self-contradictions, more easily noticeable through a stranger’s eyes.

This two-book project is about the overlapping and distinctive experiences and literary representations of Arab, Persian, North and East African, South and Southeast Asian Muslims in Britain from the eighteenth century onwards. The current book is about the two centuries leading up to the publication of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (1988) and resultant controversy. Britain Through Muslim Eyes has two trajectories: its warp is the broadly chronological threads, but genre is its weft. Part I is devoted to what I call ‘travelling autobiographies’, such as (though not including) the Shah’s. The second, longer Part looks at ‘travelling fiction’. Even if these are positioned separately, it is important to read across the fiction/non-fiction divide in relation to these writers and this long period. The dynamic titles of the book’s two Parts are influenced by Edward W. Said’s concept of ‘traveling theory’ (1984) and Margaret Cohen’s notion of ‘traveling genres’ (2003). In his chapter ‘Traveling Theory’, Said analyses the ways in which ideas travel ‘from person to person, from situation to situation, from one period to another’ (1984: 226), and – he suggests further – from discipline to discipline. Literary genre is not something to which Said accords much attention in this work, except in relation to the blurred lines between literary theory/criticism and other types of academic study. It is here that Cohen comes in. She examines the portability of creative genres across national boundaries, arguing that the novel is a uniquely nomadic form. Taking nineteenth-century sea fiction as her case study, she suggests that this is one of the most translatable subgenres of novel because it easily adjusts to new contexts. I agree that the novel is a highly ambulatory form, but add travel and life writing to the list of movable genres. Not only do they assimilate and adapt in various spatial and temporal contexts, but the travelling genres of fiction, travelogue, and autobiography also orbit, and sometimes collide with, each other.

This isn’t another post-9/11 literature project and nor is it a historical sourcebook, but rather unites the politicization of post-9/11 studies with the longer range of history. Britain Through Muslim Eyes is less a literary history than a critical work, in which historical material supports the readings. Events of the period in both hostland and homelands are not fleshed out in full detail, but are instead explored when they are evoked in the texts, which provide the primary focus. When I began writing this book, I only anticipated writing one pre-1980s chapter, because few people are aware of the wealth of literature that was produced in the period before 1988. My plans changed as the archive revealed increasing amounts of writing by Muslims in Britain that predated Rushdie, often by a century or two. Additionally, in 2012 I took up a new academic position at the Department of English and Related Literature at the University of York. In the Department’s fertile cross- period and multilingual environment, I was inspired to turn the book into two volumes. This first book contains five pre-Rushdie chapters, and most of the analysed texts were written in languages other than English. The project therefore chimes with the archival turn taken by postcolonial studies over the last decade or so – as well as the roughly concomitant rise in popularity of world literature, with its emphasis on translation.

My next book, Muslim Representations of Britain, 1988–Present, will open with a chapter on The Satanic Verses, which is a turning point for Muslim writing in Britain. After the publication of Rushdie’s divisive novel, there was an upsurge in depictions of Muslims from the early 1990s onwards. The rest of the second volume will be about the long shadow the book and affair cast on contemporary literary representations of and by Muslims in Britain. This kind of century- spanning approach has been brought to Muslim history already (Matar, 1998, 2009; Ansari, 2004). However, a long view on the British context has not been taken in literary studies since Byron Porter Smith’s Islam in English Literature (1939). Porter Smith directs his vision towards the ways in which the English literature of such authors as Shakespeare, Dryden, and Milton was affected by encounters with Islam. I train my critical gaze in the opposite direction, analysing the impact on Muslim writers of their stays in Britain. In addition, the political terms of the engagement have of course changed radically since his book came out in the late 1930s.

In the contemporary period, only Amin Malak with his global perspective has attempted to bring together cross-period writings by Muslims from various ethnic backgrounds. Malak’s Muslim Narratives and the Discourse of English (2005) laid the intellectual foundations for those of us working in the field of Muslim writing. His is the first, and to my knowledge only, monograph to incorporate a relatively broad temporal sweep, from Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s ‘Sultana’s Dream’ (1905) and Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi (1940) to Ahdaf Soueif’s The Map of Love (1999). Malak’s geographical reach is ambitious too, encompassing Anglophone literary production by Muslims around the globe. I contrastingly drill down on Britain as a location for writing and for authors’ country of residence, but am not restricted to English-language literary production. Malak’s decision to explore the work of Muslim writers around the world using ‘the discourse of English’ leads to some lacunae because he is handling so vast a canvas. For instance, he claims that Bengali woman writer Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s ‘Sultana’s Dream’ was the ‘first work of fiction written in English by a Muslim’ (2005: 3). From the British standpoint, that honour, in fact, goes to Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall’s 1903 novel Saïd the Fisherman (see Chapter 3). Discussion of the convert community that includes Pickthall is featured here, an aspect that makes this book distinctive. On the other hand, Malak is right to draw attention to Rokeya’s little-known, politically even-handed fiction. This book has its own limitations, and the fact that she never wrote directly about Britain, only about Britons encountered in India, precludes her from this study.

The first criterion for including writers in this two-volume series is that they have to be of Muslim heritage, or to have converted. Put another way, they view Islam from the inside even if they are unbelievers. The book is not about European views of South Asia or the Arab world. I do not discuss non-Muslim writers representing Muslims from the early period such as James Morier or Montesquieu and, in more recent times, literary fiction authors including Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, and Sebastian Faulks, who are routinely discussed in studies of post-9/11 literature. The focus on Muslim authors also, unfortunately, precludes detailed analysis of Arab Christian writers such as Assaad Y. Kayat (b. 1811), Waguih Ghali (d. 1969), and Louis Awad (1915–90). For this book’s purposes, it doesn’t matter what nationality or ethnicity a writer is, but religious background is central. As in my previous book, British Muslim Fictions (Chambers, 2011a: 11), I am uninterested in ‘plac[ing] the writers on a scale according to the perceived ardour of their religious beliefs’. Rasheed el-Enany’s Arab Representations of the Occident (2006), Geoffrey Nash’s The Anglo–Arab Encounter (2007), and Ruvani Ranasinha’s South Asian Writers in Twentieth-Century Britain (2007) are crucial forebears to the current research. The first two monographs are solely about Arab writers, whether Muslim or Christian, while Ranasinha examines South Asian writers from all different religions.

The second prerequisite for inclusion here is that each book discussed has to be at least partly set in Britain. This is a departure from British Muslim Fictions, where the key criterion was the writers’ country of residence. That book’s 13 interviewed writers were placed under the umbrella term ‘British’, regardless of whether they were writing about Britain, to make the politicized point that Britishness should be an inclusive category. In Britain Through Muslim Eyes, the focus shifts to literary representations of, rather than residency in, Britain. The first travelogue ever to be written in English by Sake Dean Mahomed is only briefly discussed in Chapter 1 because its descriptions are of India for a European audience. Indeed, this is a common tendency in the period: the Indian writers (some of whom are Muslim) based in Britain already researched in the excellent Making Britain project (Ahmed and Mukherjee, 2012; Nasta, 2012; Ranasinha et al., 2012) overwhelmingly looked at India rather than Britain. For example, Ahmed Ali spent time in London and was involved alongside Sajjad Zaheer in the leftist group the Progressive Writers’ Association, but never wrote about Britain. I discuss Zaheer’s novella A Night in London (1938) in detail in Chapter 3, but Ali is only examined in passing because he forgoes Britain as a setting. Writer and film director K. Ahmed Abbas lived in London in the 1940s and his interest, too, in short story collections such as Rice (1947), was India rather than Britain. Another author, Sirdar Ikbal Ali Shah, for the most part engaged himself in an attempt to explain ‘the East’ to ‘the West’. However, he also gave lectures to poor, mostly Muslim lascars (seamen) in London’s East End and lived in Britain for approximately half a century, between 1914 and 1960. He was the father of Idries Shah, the famous Sufi mystic who was also Doris Lessing’s teacher, and wrote a biography (1933) of Aga Khan III, Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah, whose work I discuss in Chapter 2. Then there was Attia Hosain, who came to Britain a bit later, in 1947. Hosain is best known for her fiction about India, Phoenix Fled (1953) and Sunlight on a Broken Column (1961). She only wrote about Britain in an unfinished novel, ‘No New Lands, No New Seas’, which she wrote between the 1950s and 1970s; it was published posthumously in 2012 (see Chapter 4).

In relation to the Arab writers, Britain did not even come close to being the most popular European country in their imaginative terrain. France inspires far more literary representations than Britain, probably because of its widespread and assimilatory colonial project in the Maghreb, as compared with Britain’s penumbrous enterprise of setting up semi-autonomous protectorates in Middle Eastern countries such as Egypt. Britain appears to feature roughly as regularly in Arab cultural production as four other European nations: Austria, Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands (el-Enany, 2006).

Staying with the issue of location, one of the characteristics of the texts under analysis is how difficult it is to contain them within a single British location. Not one of the travel and life writers, and only Zaheer, Hosain, and Tariq Mehmood from among the authors of fiction, use an exclusively British setting (and even these three provide flashbacks about their characters’ previous homes in South Asia). These are highly transnational authors, whose characters are similarly shape- shifting wanderers. For them, Britain is a (perhaps temporary) home and a writing preoccupation, but also a conduit to other countries and imaginative realms. In The Long Space: Transnationalism and Postcolonial Form (2009), Peter Hitchcock associates the term ‘transnational’ with ‘that which is beyond nation and its suffocating prescriptions’, calling to mind ‘the passport with copious stamps and extra pages; the ward of book covers with exotic names and palm fronds; the impress of a massive translation machine’ (2009: 5). These are evocative ideas in relation to the chosen writers, most of whom feel ambivalent or even antagonistic towards their originary nation and nationalism. Of the 21 authors under discussion, only nine write their work in English, mean- ing that more than half the texts are translated from the original Arabic, Persian, or Urdu. If it is an exaggeration to suggest that these books engender a ‘massive translation machine’, which, Hitchcock elucidates, is ‘sufficient to convert there to here in hardback, paperback, or digital download’ (2009: 5), nonetheless an ample translation mechanism exists to ensure that they are all readily available in English.

Hitchcock’s brief allusion to the politics of publishing and marketers’ drive to exoticize world literature is resonant for one of the key authors in particular: the contemporary Egyptian–British women writer Ahdaf Soueif. The 1983 short story collection of hers which I scrutinize in this volume goes by the ‘exotic name’ of Aisha and features a sunset- drenched riverbank (Nile?) locale, replete with the obligatory ‘palm fronds’. According to Sharifa Alamri, this type of landscape is common on Soueif’s book covers because she has ‘a veto in her contract with publishers prohibiting Islamophobic images of mosques and veiled women’ (2014: 155). Finally, Hitchcock goes on to explicate that transnational culture results in ‘a broad […], egalitarian, and conflictual novelistic space of negotiation’ (2009: 14). As we will see, the content and form of these texts is diverse and sometimes opposed, but many of their authors disclose egalitarian views (and some, like Ahmad Fāris al-Shidyāq, Zaheer, and Hosain are involved, to greater and lesser degrees, in socialist political organizations).

My next criterion is that the writers have to have paid at least some attention to Muslim characters. Many go much further than that, portraying Muslims’ everyday lives and de-otherizing this religious group, which, as Said’s research demonstrates, has long been othered (1995, 1997). This approach means that I am not so interested in novels such as Pickthall’s All Fools (1900) or Zulfikar Ghose’s Crump’s Terms (1975), which deal with Britain but do not portray any Muslim characters. Instead, I concentrate on other books by these authors – Pickthall’s Saïd the Fisherman, ‘Karàkter’ (1911), and ‘Between Ourselves’ (1922a), and Ghose’s autobiography Confessions of a Native-Alien (1965) – which fulfil the two criteria of being at least partly set in Britain and focusing on Muslim characters. Similarly, in the next monograph, Hanif Kureishi’s texts that deal with white Britain such as the novella Gabriel’s Gift (2001) and film Le Week-end (2013) are not nearly as central to my research as those that deal with race and religion, such as The Buddha of Suburbia (1990), The Black Album (1995), ‘My Son the Fanatic’ (1997b), Something to Tell You (2008), and The Last Word (2014).

The next yardstick for inclusion in this study is that authors have to have written texts that are in the public domain and available in English (whether originally written in that language or translated). Again, this is different from the Making Britain project, database, and associated books, which examine South Asian public figures including, but not limited to, writers. For example, in Rehana Ahmed and Sumita Mukherjee’s South Asian Resistances in Britain, 1858–1947 (2012), they and other scholars including Florian Stadtler explore political personages. These include General Michael O’Dwyer’s assassin Udham Singh, and Krishna Menon, who is better known for his activism than his publishing and editorial work, alongside more straightforwardly ‘literary’ individuals such as Mulk Raj Anand. I wanted to include in this book discussion of that important figure to history and the literary imagination, Queen Victoria’s munshi, Abdul Karim. He is from the ranks of the many South Asian Muslim servants who came to Britain in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While we know that Abdul Karim wrote journals because Shrabani Basu draws upon them in her captivating book Victoria and Abdul (2011), these are kept privately by his descendants. With regret, therefore, Abdul Karim only makes a short appearance among these pages in discussion of the Aga Khan’s encounters with this favourite aide of Victoria’s. Although the surveyed writing comprises a politically crucial and aesthetically high-quality body of work, there is no doubt that for much of the period and in relation to most of its authors and characters it is elitist in class terms. In the second book in this series, Muslim Representations of Britain, 1988–Present, I will expand the scope further to discuss representations of a more diverse social group, including lascars, servants, and soldiers.

Another touchstone for admittance in the current volume has to do with genre. After much internal debate, I decided to discuss only travelogues, autobiographies, and fiction (short stories, novellas, and novels). I have already published articles on Muslims in poetry (Chambers, 2011b), children’s literature (Chambers and Chaplin, 2012), and publishing (Chambers, 2010), so I decided not to venture down these avenues again. More positively, and as I discuss in Chapter 2, there is slippage between autobiography, fiction, and travel writing, which means that it would be unhelpful to cordon off the three genres.

I found that the authors use a wide variety of genres, experiment with their elastic boundaries, and engage in debates about the politics of form. Of course, not all the Muslim writers of fiction march in the same direction, but from the early twentieth century onwards they seem more interested in quasi-modernist experimentation than in realist plain style. Margaret Cohen argues that in the Victorian era, ‘writers used a single poetics, historical realism’, whereas in the twentieth century ‘modernism was to become the “international style” in the domain of visual culture and the decorative arts’ (2003: 481–2). This sweeping statement is useful, particularly given Cohen’s insistence that literary modes such as realism and modernism cannot be subsumed as the property of a particular nation or continent. My lone nineteenth-century novel, al-Shidyāq’s Arabic-language Leg Over Leg (1855), is generically hybrid. It has greater formalist affinity with the stream-of- consciousness modernist fiction of five decades later than with its realist Anglophone contemporary, Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (also 1855). I explore the way in which hybridized modernist techniques and aesthetics recur in different ways through this period. Realism does also feature in this body of work, though to a lesser extent − for example, in Mehmood’s and Abdulrazak Gurnah’s layering up of painful details about racism in their respective texts ‘The Return Journey’ (1983) and Pilgrims Way (1988).

In relation to genre, the fiction authors produce many short stories and novellas, far more than novels. My inclination is to read Zaheer’s A Night in London, Hakki’s ‘The Lamp of Umm Hashim’ (1944), Hussein’s ‘The Journey Back’ (1981), and Mehmood’s Hand on the Sun (1983) as novellas rather than long short stories, despite the generic ambiguity that surrounds them. Georg Lukács’s theorization of the novella form in Solzhenitsyn (1970) is illuminating in this regard. Lukács’s Marxism leads him to situate novellas within the categories either of the vanguard or rearguard. According to him, the form ‘appear[s] historically both as a forerunner and rearguard of the great forms; it can be the artistic representative of the Not-Yet or of the No-Longer’ (1970: 8). Certainly some of the left-leaning Muslim writers represented in this book, most notably Zaheer, saw themselves as part of a vanguard working to usher in (as the Progressive Writers’ Association Manifesto puts it) ‘literature of a progressive nature and of a high technical standard’ (Zaheer, 2011: n.p.). More widely applicable is Lukács’s crisp definition of the form:

the novella is based on a single situation and – on the level of plot and characters – remains there. It does not claim to shape the whole of social reality, nor even to depict that whole as it appears from the vantage point of a fundamental and topical problem. […] For this reason the novella can omit the social genesis of the characters, their relationships, the situations in which they act. Also for this reason, it needs no agencies to set these situations in motion and can forgo concrete perspectives. This peculiarity of the novella […] permits an infinite internal variety from Boccaccio to Chekhov. (1970: 8)

The diverse shorthand form of the novella, then, is ideally placed to represent one or two individual issues, and liberates its author from the spadework of contextualization.

Additionally, I discuss Pickthall’s, Qurratulain Hyder’s and Ghulam Abbas’s short stories, Ahdaf Soueif’s story collection Aisha (1983), and Attia Hosain’s ‘No New Lands, No New Seas’, which is a posthumously published novel fragment. Only Pickthall’s Saïd the Fisherman (1903), Hyder’s River of Fire (1959), Salih’s Season of Migration to the North (1966), and Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Pilgrims Way can be classified unambiguously as novels. That the novella and the short story are the most popular forms among early Muslim practitioners of fiction about Britain can partly be accounted for by economics. Writing in the 1930s, Shaista Akhtar Banu Suhrawardy claims that whereas it is universally difficult for an untested author to find a publisher, this is especially true in South Asia. The young writer more readily publishes stories in magazines, she contests, and then ‘it becomes a much easier task for him [sic] to get a publisher to agree to publish a collection of his [sic] works’ (1945: 304). From the perspective of Arabic letters, miriam cooke observes that Hakki, the author of many short stories and the novella ‘The Lamp of Umm Hashim’, often inveighed against the West’s ‘unfair material advantages’. According to cooke, Hakki felt that only Western authors ‘could afford the luxury of the novel’ (1981: 22) and that they often stretched material thinly over the novel’s generous framework. By the middle of the twentieth century and beyond, Arabic writers tended not to be accorded the same space and freedom for loquacity. In both Urdu and Arabic literature, therefore, short stories and novellas are admired, accessible forms, both with writers and readers.

Before the examination of travel and life writing which follows in Chapters 1 and 2, it is worth emphasizing the originality of this research. The books studied in Part I are not canonical Black British Ur-texts by writers such as Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho (1994). Although Michael H. Fisher (1996) and C. L. Innes (2008: 46–55) inter alia explore Dean Mahomed’s writing in their excellent studies, the other writers (Mirza Sheikh I’tesamuddin, Mirza Abu Taleb Khan, Najaf Koolee Meerza, Atiya Fyzee, Maimoona Sultan, the Aga Khan, Zulfikar Ghose, and Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra) have been relatively neglected. Still less work has been done to analyse these travel writers together as part of a group of early Muslims in Britain. For example, Sukhdev Sandhu (2003) positions Mahomed, Abu Taleb, and others within a multicultural London framing; both he and Innes also have a Black and Asian British perspective; while Rozina Visram (1986, 2002) and Michael Fisher (1996, 2004) are interested in South Asians in Britain. To my knowledge, South Asian migrants have only been scrutinized alongside Arabs and Persians in Britain in the history books by Matar and Ansari already mentioned, rather than in any literary study taking a long view.

The language issue is also something I want to flag up from the outset. Clearly, there is no single ‘Muslim language’, so it has been necessary to include an admixture of English and texts translated from other languages. Following Amin Malak’s lead, British Muslim fiction stud- ies tends to confine itself to Anglophone literary production. However, my book shows that in the early period, English was outnumbered by other languages by a ratio of more than 2:1. Translation, both linguis- tic and cultural, is also a central theme in several of the novels. In the contemporary period, there is even a novel entitled The Translator that deals extensively with issues surrounding translation (Aboulela, 2001). In Muslim Representations of Britain, 1988–Present, I will discuss this book by the Sudanese author Leila Aboulela, as well as Pakistani writer Aamer Hussein’s recent move from Anglophone production into Urdu only to translate his own stories back into English. I must acknowledge my own limitations as a linguist. I have a little conversational Urdu but am functionally illiterate in it, know only a few words of Arabic, Bengali, and Persian, and nothing at all of Malay or Kiswahili. This means that this book is reliant on translations to access these rich literary texts. Ziad Elmarsafy writes, ‘Translation is the most political art’, and goes on to suggest that it can be theorized as thick description (2009: ix, 27). By linking translation to the methodology of anthropology, Elmarsafy calls to mind Susan Bassnett and Harish Trivedi’s translation theory (1999), and Talal Asad and John Dixon’s work on the relationship between anthropology and translation (1985). Bassnett and Trivedi argue that translation has long been entangled in the web of imperial power. Translation, they suggest, usually takes place in a unidirectional process, with texts from non-Western countries being laid open to the authoritative scrutiny of the West. Asad and Dixon similarly emphasize the unequal statuses of languages in the colonial and post- or neocolonial worlds. They argue that the metamorphosis of language enthusiastically envisioned by such theorists as Walter Benjamin is more likely to occur in a culturally weak language than in one as politically and economically dominant as English. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (herself an adept translator of Jacques Derrida and Mahasweta Devi, among others) hails translation as ‘the most intimate act of reading’ (2005: 94). It has to seduce the reader into entering an unfamiliar world and seeing a world through the eyes of an/other. Therefore, while translation is a highly politicized, unequal, and epistemically violent process, it also has its pleasures and rewards.

It is also necessary briefly to flag up the question of audience. Some of the travel and life writers (I’tesamuddin, Atiya, Maimoona, and Tunku) and non-Anglophone authors more broadly (Zaheer, Hakki, Hussein) are clearly aiming their books at their compatriots back home. This is partly signalled by their decision to write in the home language. That said, other non-Anglophone texts have more cosmopolitan influences and the cultural background of their ideal reader is less straightforward. For example, critics are divided over Abu Taleb’s audience. Kate Teltscher (2000: 410), Tabish Khair (2001: 35), and Jagvinder Gill (2010: 125) argue that he wrote his Persian-language Travels for upper-class Indo–Persian readers. By contrast, Nigel Leask (2006) suggests that Abu Taleb always intended his travelogue to be consumed by European read- ers as well. Leask supports his out of step argument with the evidence that the Travels was translated quickly, within a decade of being writ- ten. It was immediately reviewed in the 1810 issue of Quarterly Review (Heber, 1810). At one point in his review, Reginald Heber writes that Abu Taleb ‘taxes us pretty smartly’ (1810: 89) with his criticisms of British people, suggesting that Abu Taleb had his eye on the British response to his Persian-language text. The review is evidence of the metropolitan reception of Abu Taleb’s work and indicates that this travel writer in some ways sought to challenge and even provoke readers in Britain. Leask suggests that Abu Taleb would have had some knowledge of the eighteenth-century ‘informant narrative’ genre featuring fictional Eastern personae, such as Montesquieu’s Persian Letters (1721) and Goldsmith’s The Citizen of the World (1820). Returning to the broader issue of audience, in the pre-twentieth-century Muslim travel writing from languages other than English, uncritical adulation of the West is often intended as an indictment of problems or corruption at home (Horsman, 2011: 231). By contrast, in texts originally written in English, there is likely to exist a burden of representation (Mercer, 1994: 235) which attaches to depictions of the other when aiming at a Western audience. From the 1960s onwards, there is also a rapidly growing British Muslim readership keen for literature that reflects their experiences.

The Muslims from South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East discussed in this monograph have a religious worldview and history that productively overlaps via shared experiences of colonialism, the Non- Aligned Movement, or Third World politics, and now the repercussions of the War on Terror. There are many differences and distinctions as well, dramatized most recently by the Arab uprisings. The revolutions and protest movements especially prominent in the Arab world from the end of 2010 onwards have had little impact on African, South or Southeast Asian Muslims in their home countries. A different picture emerges from the contemporary diaspora, where some young Muslims of all different ethnicities have been radicalized by what they see as the oppression of fellow Muslims in the Syrian Civil War in particular.

South Asians and Arabs are the dominant ethnic literary voices in this volume, with 13 of the authors coming from South Asia (at least three of them have ancestry in Iran) and four from the Arab world. This reflects their status as two of the numerically biggest populations of Muslims (there are now 1,830,560 Muslims who identify as ‘Asian or Asian British’,6 and 178,195 Muslim Arabs in England and Wales (DC2201EW, 2013: n. pag.)). Of the remaining four writers, Pickthall is a white convert, Abdulrazak Gurnah is from Zanzibar in East Africa, Malaysian Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra is the book’s lone Southeast Asian representative, and Najaf Koolee Meerza is one of three Iranian princes who came to Britain in 1836.

I have aimed for as much comprehensiveness as possible in relation to the Muslim fiction that starts to emerge in the middle of the nineteenth century. It was beyond the scope of this book, however, to include all of the vast wealth of travel and life writing produced by Muslims about Britain between 1780 and 1988. I particularly regret four exclusions: the travelogue of Naser-ed-Din Shah Qajar, with whose quotation I began this Introduction, that of Indian Muslim philosopher and activist Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (Hasan and Zaidi, 2011), Yusuf Khan Kambalposh’s Between Worlds (Hasan and Zaidi, 2014), and Changing India by woman writer and activist Iqbalunnisa Hussain (2015). I hope to supplement this book with papers on these four books in the future. I was also disappointed not to uncover any life and travel writing or fiction by Turkish authors, despite serious searching. This will to some extent be righted in the next book, in which Elif Shafak’s Honour (2012) is a key text. One of my aims in this project is to spearhead the formation of an inclusive but formally innovative British Muslim literary canon. That is why I have tried to be as all-embracing as pos- sible in this book. The next volume will have to be more selective, despite dealing with a much shorter period, because this body of writing has simply exploded in the years since The Satanic Verses was first published.

I am indebted to Nabil Matar’s Europe Through Arab Eyes, 1578–1727 (2009) for Britain Through Muslim Eyes’ title, and to Rasheed el-Enany’s Arab Representations of the Occident (2006) for that of the sequel, Muslim Representations of Britain, 1988–Present. These monographs were also constitutive of this project’s intellectual trajectory. Matar furnished much historical information about the period that ended 50 years before this book takes up the story. The structure of el-Enany’s exemplary literary critical work provided the broad inspiration behind my decisions to divide each chapter up into sections about the individual writers, and also to trace different phases in the various periods’ literary representations. As a bilingual scholar, el-Enany is able to be truly compendious, discussing 56 authors compared with my 21, but only rarely bringing in other critics’ work to supplement his supple readings. El-Enany explores dozens of Arabic- language literary works – several of which are available in English transla- tion but most which are not – as well as discussing the Anglophone authors Waguih Ghali, Ahdaf Soueif, and Leila Aboulela (2006: 84–6, 200–4).

The emphasis on Muslim eyes necessitates some discussion of the gaze. Jacques Lacan most famously provided psychoanalytical explorations of the gaze in his essay ‘Of the Gaze as Objet Petit a’ (1978). The gaze is bound up with Lacan’s notion of the Mirror Stage. He uses the Mirror Stage to symbolize the moment in a child’s life when it sees its own reflection and realizes that it is separate from its mother. At this point, the child leaves the Imaginary world – associated with the mother’s body, a composite identity, and incoherent babbling – and enters the Real or Symbolic realm, where ‘the Rule of the Father’ is paramount, identity becomes fixed and complete, and language is acquired. In the complex and much-disputed theory of Lacanian psychoanalysis, the gaze is less about the other than the self’s identity. John Urry, in his The Tourist Gaze (2001), explores the various impulsions and unequal power relations that cause societies to gaze upon others, and what this tells us about the society doing the gazing. Urry’s text is especially important for broadening the gaze out to postcolonial perspectives. Luce Irigaray challenges the ‘predominance of the visual’ in patriarchal Western societies from the ancient Greeks onwards (1985: 25). This ocularcentrism is challenged from an Arab feminist point of view by Algerian writer Assia Djebar. In her essay ‘Forbidden Gaze, Severed Sound’ (1992), Djebar takes up the idea of the prevailing ‘male gaze’, but explores, firstly, the control that men have over the gaze received by women, and secondly, how women are prevented from orchestrating their own gaze and are silenced. We will see that images of eyes, optics, and the gaze recur in the primary texts. For example, the Arab migrant character Saïd from Pickthall’s Saïd the Fisherman gazes lecherously but impotently at British women, Hakki’s ‘The Lamp of Umm Hashim’ is full of sight/blindness metaphors, while Mustafa Sa’eed’s gaze is foregrounded in Salih’s Season of Migration to the North. In each of these examples, Djebar’s Arab feminist argument together with Urry’s postcolonial standpoint provides useful insights.

A significant finding from British Muslim Fictions was that contemporary writers fall into three categories: ‘a British-born group, writers who arrived in Britain at an impressionable age, in their teens or early twenties, and an exilic group who use Britain as a perhaps temporary base’ (2011a: 24). In the recent writing surveyed in this interviews book, in Muslim Representations of Britain, 1988–Present, and Chapter 5 of this monograph, the bulk of writers are people who came to Britain at a formative age and stayed on. However, in the pre-1980s period studied here in Chapters 1–4, the majority belongs to the exilic group stay- ing temporarily in Britain. Consequently, much of this book is about Muslim writers who came to Britain for a substantial length of time and then ‘returned’, changed by their experiences, to the home country. Only six out of the 21 writers (Mahomed, Pickthall – who is anyway somewhat anomalous due to his convert status – Hosain, Mehmood, Soueif, and Gurnah) stay on in Britain and are not exiles.

The last three permanent settlers, Mehmood, Soueif, and Gurnah, are all writers who began their careers in the 1980s, whereas there are decades-long gaps separating the early three. During the 200-year period, therefore, a broad shift is noticeable from what we might term ‘England-returned’ to ‘myth of return’ writers, which suddenly speeds up in its final decade. ‘England-returned’ is a term used in South Asia to refer to people who have been educated all over the UK, not necessarily just in England. The expression is used by Sumita Mukherjee to describe South Asian students in Britain, in her enlightening history Nationalism, Education and Migrant Identities: The England-Returned (2011). However, I am probably the first person to examine this social class’s literary output. Clearly, issues attach to the phrase’s assumption that England and Britain are synonymous, and to the fact that it originates in South Asia rather than the Middle East, Africa, or Southeast Asia. The Hindi and Urdu terms ‘Vilayet-palat’ or ‘Vilayet say waapsi’ are colloquial phrases used by the travellers and their relatives to denote one who has returned from any foreign country, but more often the English phrase ‘foreign-returned’ is dropped into conversations in the vernacular. ‘Vilayet’ is not specific to one particular country, so another phrase that is used is ‘Inglistan-palat’ ‘Inglistan say waapsi’ for England (Britain) -returned. The Bengali equivalent of ‘foreign-returned’ is ‘Biletpherat’, which is also the title of N. C. Laharry and Dhirendranath Ganguly’s satirical film (1921) about a foreign-educated man’s return to conservative Bengal with shockingly Westernized ideas about love and marriage. There is no direct Arabic equivalent for ‘England-returned’. ‘Al-Londony’ seems to be the closest equivalent; it means ‘the Londoner’, the final ‘y’ being the genitive suffix. Several of the Arab writers and characters become known as al-Londony or variants of this term when they return to the Arab world after studying in Britain. Whereas the Indian languages often take ‘England’ to stand in for Britain, Arabic moves further inward, using ‘London’ as a touchstone for the whole country. It should be noted, though, that the Britain these writers explore is for the most part England and, more specifically, London. This alters towards the end of the period, and we observe in Chapter 5’s 1980s narratives a move away from the capital to the provincial cities of Birmingham, Bradford, and Canterbury. The shift to the first two northern cities is due to their industries – textile, steel, and vehicle manufacture – experiencing a labour shortage that South Asian Muslim migrants filled. The devolutionary trend accelerates in the post-Rushdie period, with the other countries of Britain, particularly Scotland, featuring ever more prominently.

My thesis is that towards the end of the designated period, authors tend not to return to their own countries any longer and are increas- ingly from the more proletarian ‘myth of return’ class. By the mid- to late twentieth century, South Asian Muslim migration was characterized by chain migration, in which a group of ‘pioneer’ migrants came to Britain and subsequently sponsored relatives and friends to come. They retained village–kin networks (biradari) and strong links to the home country (Dahya, 1974: 99–100). Working-class South Asian Muslim settlers in the postwar period saw themselves as transients and were motivated by the ‘myth of return’ (Dahya, 1974: 78, 83, 99; Anwar, 1979). They planned to save, send money home, and go back to Pakistan as soon as they had made enough. However, ‘[i]n reality, most of them are here to stay because of economic reasons and their children’s future’ (Anwar, 1979: ix). Especially as families began to be reunited in Britain, they became interested in building self-sufficient communities. The model of Arab migration is different: more middle-class and less visible, as we will see ( p. 205). However, the trend is the same that early visitors tended to go back after a few years, whereas those who arrived after about 1960 were more likely to stay. An Arab version of ‘myth of return migrants’ could be expressed through Fred Halliday’s formulation ‘immigrant communities’. In Arabs in Exile (1992), Halliday uses the term to denote ‘a group of Arabs who have not merely come to Britain for a period of residence’, but have rather worked there while remaining in touch with ‘fellow emigrants’ from their part of the world (1992: 2). Similarly, Humayan Ansari divides his supraethnic ‘The Infidel Within’: Muslims in Britain Since 1800 (2004) into two parts: ‘Arriving, 1800–1945’ and ‘Staying – 1945 Onwards’. As such, an alternative pair of terms could have been ‘arrivers’ and ‘stayers’, but this seems inelegant. Additionally, I like the emphasis on return in the ‘England-returned’ and ‘myth of return’ migrant group designations, since many of these texts are preoccupied by the return to the ‘home’ country after a period of time in Britain.

Illustration 1 Taj Mahal curry restaurant, Bristol, c.1970. Credit: Monira Ahmed Chowdhury and Hasan Ahmed.

My cover image is illustrative of a necessary caveat. The generalization we can make about a transition from the pre-1960s migrant writers mostly being England-returned, to the authors of the 1970s onwards belonging to the myth of return group is neither total nor uniform. The cover image based on the illustration ‘Mahomed’s Baths’ (1826) suggests much about the multitude of Muslims who did settle in Britain in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, most of whom did not write. Dean Mahomed is unique amongst the pre-twentieth-century writers for having lived a far greater proportion of his life in Britain than the home country, marrying an Irish woman, and bringing up British children. However, many non-scribbling lascars, servants, students, and others similarly put down permanent roots in Britain. The picture tacitly speaks against the populist misconception that the ‘British Muslim’ is a recent, alien aberration. Mahomed opened this new building for an already successful massage baths in Brighton in 1821, the same year that the nearby pseudo-Indian Royal Pavilion’s architecture was completed (Visram, 2002: 42). Indian soldiers would later be treated for their injuries in the Pavilion during the First World War (Visram, 2002: 181–8; Shamsie, 2014), again demonstrating the long history and value added by Muslims to British history.

A word, too, needs to be said about Illustration 1, above. It is a photograph taken around 1970 of a curry restaurant in Bristol. The late owner’s daughter, Monira Ahmed Chowdhury, writes that the photograph depicts her father, Feroze Ahmed, in front of the first restaurant he opened, the Taj Mahal, at 58 Stokes Croft in Bristol (Chowdhury, 2014). From Sylheti Muslim stock, Feroze was a pioneer of Indian restaurants in the southwest of England. Shortly before his death in 2000, he wrote a short essay for a collection of personal reflections about migration to Bristol (Ahmed, 1998). In it, he describes moving from Oxford in 1959 to open Bristol’s first ‘Indian’ restaurant. He also opened the second (named Koh-i-Noor) and third restaurants in Bristol and the inaugural Indian restaurant (another Taj Mahal) in Bath, revolutionizing West Country cuisine. In 1961, Feroze went back to what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to get married. His wife Asma Ahmed departed with him soon after the wedding to make a new life in the UK and she was the only Bengali woman in Somerset for more than five years. She was not to meet another woman from her background for two years until she encountered another Bengali wife in London. Interestingly, Feroze describes her loneliness in relation to ingredient shortages in Britain: ‘she was alone 24 hours a day … there was no chilli, no paan, nothing’ (Ahmed, 1998: 104). In his article about British curry history, Ben Highmore lays emphasis on the racism and unpaid food bills of which restaurateurs including Feroze were on the receiving end (2009: 183). This is important, and the thread on ‘Indian’ restaurants in this book will also stress these difficulties. However, for the purposes of this book’s interest in the movement from England-returned to myth of return migrants, here are Feroze’s reflections on permanency:

When I came to England, I didn’t come here to live for ever, for always. I was a student first, and then I started work. […] I have spent 40 years here, but now because I have not been well for twenty years, and have had twenty years of not being active, what can I do? One part of my life has gone – work. Now I feel that all my children have been educated and can live anywhere in the world, that’s OK. But I don’t want somebody to insist that I stay in England. My heart is in Bangladesh. (Ahmed, 1998: 106)

He summarizes the intentions of many myth of return migrants when he states that his intention was to study and make money before return- ing, but before he knew it 40 years had passed in this alien land. After experiencing what he describes as a ‘massive’ but non-fatal heart attack two decades earlier (1998: 106) and now that his kids are grown, he yearns to return to Bangladesh. Extra poignancy is added by the knowledge that he died two years later, without fulfilling this dream.

This photograph (Illustration 1), with its image of the Mini car in front of the Taj Mahal restaurant evokes the dynamic motion of the Muslim traveller explored in this book, and the centrality of arrivals and departures in the period. It also conveys to the prospective reader the contributions to material culture, particularly food (a major theme in this volume), that South Asian Muslims have made to Britain. However, it is a slight shame that both of the images for this book are connected to permanent migrants (myth of return) rather than visitors (the England-returned). For the cover image, I would have ideally chosen an archival photograph of a Muslim traveller on the deck of a ship which is either (and crucially we shouldn’t be able to tell from the photo) arriving in, or departing from, a British port. This would have conveyed the dynamism and cosmopolitanism of the writers under discussion, but unfortunately no photograph of this nature revealed itself. What the images illustrate beautifully, though, is how settled, how integrated in British life Muslims have been for several centuries, and what huge contributions they have made to the fabric of this nation. I hope that this book will do them justice.