Book Excerpt: The Footprints of Partition by Anam Zakaria

In this moving excerpt, the cricketer Intikhab Alam’s memories of Partition mirror the stories of those Hindu and Sikh refugees who streamed into India.

In this moving excerpt, the cricketer Intikhab Alam’s memories of Partition mirror the stories of those Hindu and Sikh refugees who streamed into India.

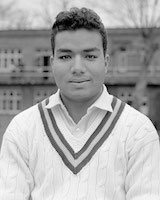

‘Ironically, I was on the last train from Simla to Lahore at Partition, and twenty-four years later, on the last flight to the West Wing before the creation of Bangladesh.’ I am sitting with Intikhab Alam, the legendary Pakistani cricketer.

… When a close friend of mine arranged the interview with Intikhab Alam, I was thrilled… yet in the hours I spent sitting with Intikhab in his house in Model Town, the topic of cricket took up no more than two or three minutes. Within seconds of our introduction, I came to realize that India was not just a place to play cricket, an enemy meant to be defeated. Rather it was home for Intikhab… it was a home of the past, one that could not deny him his childhood memories and heritage.

‘My father was an engineer, actually,’ he starts. ‘He was heading the electricity department in Simla in 1947. I was about five years old at this time.’ He sucks in air, holding his breath before continuing. ‘When it all started… things became … extremely hard because we were the only Muslim family in Simla at the time. A lot of people had left.’ I am surprised to see the difficulty with which Intikhab is speaking.

The pauses, the heavy breathing, is unexpected. He has been interviewed by numerous domestic and international media channels in the past. This is just another interview, and that too an informal one… But perhaps it’s the first time someone has asked Intikhab to speak… about his past, about Partition.

‘My father was a government servant… He was in charge of the whole electricity department, so we couldn’t leave in time. We thought we would really be okay… until the trouble started.’ As riots escalated, the Khan family became scared… and quickly scrambled into their Sikh neighbour’s home. ‘He was my father’s number two, an incredibly loyal fellow,’ explains Intikhab. ‘He came to my father one day and said: “Khan sahib you have to leave your house. Things have become very, very difficult. They won’t leave you alive.”

‘For the next three days we stayed cooped up in a small room with the Sikh family… The mob used to come and the Sikh would tell them that the Khan family had already left. They came three-four times but he continued to safeguard us till he could.’

However, as violence seeped into Simla,… Khan’s neighbour began to fear for his life as much as theirs. ‘One night he came and said, “It’s become very difficult to protect you. They want to search my house you have to leave or they’ll kill all of us.” I think it was one or twelve o’ clock when he said leave, leave now’. The Sikh, whose name Intikhab doesn’t mention, grabbed a torch and paved his way through the jungle, guiding the Khan family to the power house…

‘It took us about an hour or so to go down through the jungle to the power house and he stayed with us the whole time. I don’t know if we would have made it without his help…’

This was not the first time I was hearing of opposite sides coming to the rescue… Many people I had spoken to had narrated similar instances of compassion and support offered by the ‘other’ whether Muslim, Hindu or Sikh… Ashis Nandy’s work on Partition reveals similar findings. In conducting 1500 interviews, he found that ’40 per cent of his sample called up stories of themselves and others being helped through the orgy of blood and death by somebody from the other side’…

I had been surprised when I first came across such stories. I had conveniently assumed for the majority of my years that all Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus were at each other’s throats… increasingly, I was finding out that I had been wrong.

Intikhab tells me that that was the last time his family saw their Sikh saviour. His father’s Muslim friend, a brigadier, was going to help them from there on… To the five-year old Intikhab, all of this did not make much sense… Pakistan was just a word which used some of the new ABC alphabets he had recently learnt. It was P-A-K-I-S-T-A-N, a simple yet proud addition to his vocabulary…

‘At Kalka, it was an open field without any shelter… We spent two nights there in those conditions. I remember in the evenings they would fire and bullets would fly through our tent, which we had made out of sticks and my mother’s dupattas.’

‘Who were they?’ I interrupt. ‘Sikhs,’ He replies in a matter-of-fact way. They would fire everywhere at random,’ he pauses and… then looks at me. ‘At one end we were being helped by the Sikhs and at the other end they were attacking us. There was absolutely no logic.’

As he says this I realize how easy it is to believe that all Hindus and Sikhs were bad. Had Intikhab not narrated the story of his father’s Sikh neighbour to me, the notion of ‘big bad Sikhs’ I had come across in my school textbooks… and in news bulletins and in general discussions among people while growing up in Pakistan would only have been reinforced. But as I hear his story, the flip side of the coin, I realize how naïve it is to characterize a group of people as entirely good or bad, or a situation as complex as Partition as black or white.

The conditions were far more complicated, far more twisted than presented in our official accounts of history. How could I have believed at a point in my life that all Sikhs and Hindus had turned evil overnight and all Muslims were pure?…

‘From Kalka, we boarded a train but the situation was even worse inside… This was after Partition and by this time a Muslim, and especially an official, caught in what was now Indian territory, often had only one destiny – torture before death. The drivers would park the train in the jungle and then honk to alert the Sikhs to come kill everyone aboard. It was an open invitation.’

Intikhab leans backward… He isn’t narrating an adventure story; this was reality for him. All without any rationale for the five-year-old Intikhab or the over-sixty-year-old Khan.

‘That day there were two trains. Ghalti se – by mistake – they, the Sikhs, got the information that the first one was a goods train. The driver parked the train in the middle of a jungle and we stayed there for over three hours. The driver kept honking but no one came to inquire, to kill and the train eventually moved forward to Pakistan. At the next train they shot and shot but there was no one inside. That’s how we survived.’

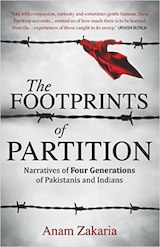

The Footprints of Partition

The Footprints of Partition

Anam Zakaria

ANAM Zakaria’s The Footprints of Partition: Narratives of Four Generations of Pakistanis and Indians is an honest and sensitive investigation into Pakistan’s traumatic birth. Born out of an oral history project that Zakaria headed for the Citizens Archive of Pakistan, the book weaves together her observations of contemporary Pakistan with memories of four generations of Pakistanis and Indians as they try to reflect and make sense of the past.