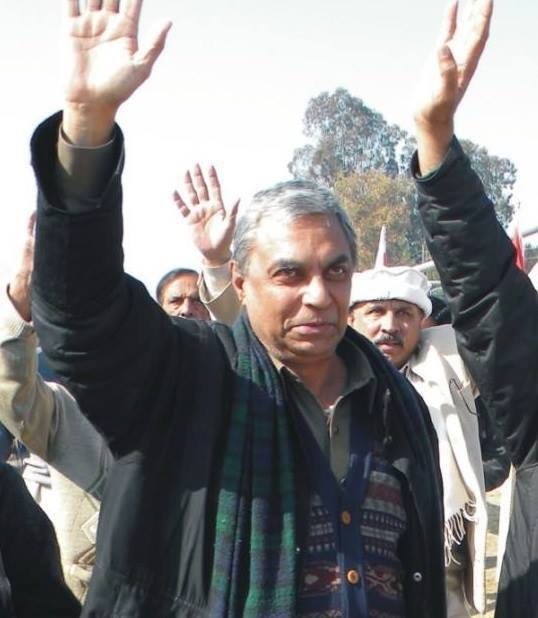

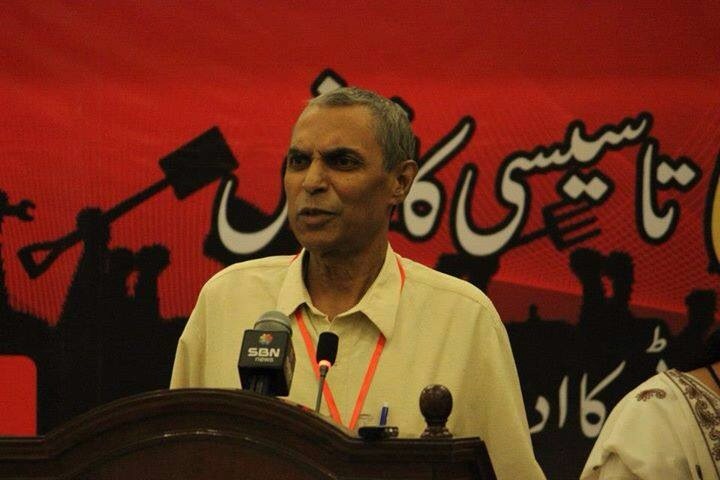

Jamil Omar (1952-2014)

ہم نے کہا ذرا قوم کو ٹھیک کرتے ہیں ، قوم نے کہا نہیں پہلے ہم تمہیں ٹھیک کرتے ہیں

ہم نے کہا ذرا قوم کو ٹھیک کرتے ہیں ، قوم نے کہا نہیں پہلے ہم تمہیں ٹھیک کرتے ہیں

That was in 1991 or so. We were meeting for the first time after ten years. Jamil was responding to my question about how the last decade had treated him. It was the first time I was seeing my friend and old Islamabad University class fellow fellow after his years of incarceration and torture in Lahore Fort to notorious Attock Jail. (Read Pervez Hoodbhoy’s Jamil Omar – Indomitable Fighter – Rest in Peace).

That was vintage Jamil and I should have known better. Humorous, brief and humbling to the point of being self-effacing. He was still grinning with sparkles of mischief and energy on his face and brilliance in his ever smiling eyes. It felt doubly embarrassing since I had already told him about my years in the US, settling down in Luxembourg etc.

The fall of 1981 marked some sort of life-changing time for both of us. In November 1981 Jamil was apprehended distributing some political pamphlets. He was to spend next few years in all sorts of jails that had earned their notoriety in torture techniques calculated to destroy human body and spirit. Just a month earlier I had left for the US for higher education. Like Jamil, I too had finally found something serious and worthwhile in life. But difference in our circumstances could not be starker. He was to spend years in cold dark underground cells. Like countless other Pakistani students in the United States I found a life both motivating and inspiring. More than anyone of us though Jamil would have excelled in any American University later pursuing a successful profession. Ironically, both the torture chambers in Pakistan and the excellent higher education system in United States had their single common sponsors – the capitalist regime pushed to extreme measures in the cold war era.

We both had ‘grown up’ since our rather care-free university days of what was then Islamabad University. We were both in the University’s Computer Science Department. Its MSc. program had not started yet and its one year diploma course was the only option for us.

By 1991 Jamil had grown up our personal version of Che Guevara whose computer printed pixelated portrait we used to hang on the walls our hostel rooms (along with that of Mona Lisa). The campus at that time was already split between its Leftist-Marxist-Maoist versus Rightist Jamaat-e-Islami politics. Our own group was not actively involved one way or the other. If ever pressed hard we would identify ourselves as liberals with various degrees of support for the leftist wings of the People’s Party. Some friends have mentioned elsewhere that even back in the Punjab University Jamil had disdain for left-right political manifestations, perhaps the whole idea of politics altogether. His only political contribution among students was to make fun of politics altogether.

In 1975-76 Jamil Omer was at the center of our rather cohesive group of friends in Computer Science. Almost all of us lived at the campus hostel. That meant our days were spent together from breakfast to the small hours of night. Most of our learning arguably happened during evenings and nights, sitting in the open-air plaza between the then three hostels with imposing Margalla hills in the background. Russian and French literature were in vogue back then. Friends were generous about sharing and exchanging books. Hostel 1 and 2 were boys while hostel 3 was for girls exclusively. Girls hostel was in the middle and was officially closed at 10pm. The last university bus would have already arrived from Aab-Para. On summer nights the boys then started to settle in the plaza nestled between the three hostels. Russian and French literature were in vogue back then. Reading smuggled copies of Das Kapital seemed perfect act of defiance, it’s fine points to be argued forever. Dostoevsky and Zola seemed natural choices in ladder for those who had already read Manto and Krishan Chandar. University’s status of public institution meant low tuition fees and acted as great class equalizer. In this the open air plaza nestled between the three hostels used to be simple criterions for deciding one’s superiority: what he had read and how intelligently he will argue it. And in a tribute to those relatively innocent days, students from left and right and the middle often engaged in heated but civilized discussions. Violence and politics among students was still a few years away.

After finishing his MSc. in Physics from the Punjab University Jamil had, like the most of us, found his way to Islamabad out of curiosity for the new field of computer science. His prior university education in physics and mathematics, his curiosity, and his above average intelligence meant that he found it relatively easy to be among the top achievers of our class. It seemed that computers and software were for him just another challenge. Being outstanding came natural to him and was mostly fun for him. Or so it appeared.

Lots of his energies found their way to all kinds of non-academic stuff. Most of it consisted of pranks and such that we all have at that age. One thing that stood out back then was his ability to be a natural leader. And with a lot of energy bubbling inside him. From cricket to hitchhiking, most of the ideas seem to come from him effortlessly. He did not like imposing on others. With his knack for encouraging others he would then find other individuals in our groups who would then carry out the tasks at hand.

His boundless energy and youth at times led to some scary moments. Like that time we all were racing to catch the University bus. Except that Jamil was with empty stomach and far ahead of us. When he collapsed totally and badly none of us were close enough. Scared as we were, we had to carry him back to the hostel in our arms. A little bed rest and some orange juice meant that Jamil was again challenging us to race to the next university bus.

There seemed to be all kinds of adventures and misadventures that kept happening around us. Like that famous idea – Jamil’s of course – to hitchhike from university to the hill station of Murree in one day. His confidence about having fine-tuned the ‘precise’ itinerary meant we arrived nowhere near Murree but completely lost and rather close to Abbottabad. Having started at 4 am in the morning, 3 hours several mountains later we ‘discovered’ a magnificent water stream that seemed natural for tea break. Except that with daylight and some rest we discovered that we had covered barely a kilometer from the starting point of the university that laid hidden behind the mountain curve. But we did discover some amazing villages in the hilly forests with its inhabitants treating us with a mix of hostility and welcome. We seemed to be outsiders invading their privacy. That did not stop them from indulging in their hospitality once they realized that we were just kids who had lost our way. If it was up to Jamil we would have continued forever. But darkness was creeping in rather fast and so was cold. Then there were increasing stories by villagers of big cats or leopards. That finally convinced us to accept villagers hospitality for warm stay with them and find next ride back to civilisation.

It seems that Jamil Omer was just being a energetic young man that he was. He was finishing his last rites of passage into adulthood, a stage back then we felt was too heavy and as such to be delayed for as long as possible. He was at the University to finish his studies like the rest of us. With what was to come in later years, he was spending last years of his youth being carefree, having fun, playing, sometimes being just silly.

I cannot be sure when Jamil decided to get into politics. I think that for most of us Zia’s coup against Bhutto changed our lives in some way or other. Or it changed at least our perspective about the country we were living in. After years of military regimes culminating in the terrible events of Bangladesh in early 1970’s the country was finally settling into an era of liberal and democratic political life. Despite autocratic and very personal ways of governing, youthful energies of Bhutto were infectious. Not a real change that the country deserved and needed but at least a semblance for it. Kind of breathing space. One could imagine the possibility of a new Pakistan. Faiz had been finally appointed as official leader for the country’s cultural life. New ways of cinematography were explored and old but rich field of folk music was discovered. Arguably just plain rhetoric but to some degree or other working rural and urban classes felt empowered. Butto’s demise in 1977 signalled end of that era. By 1979 when Bhutto was hanged, it was clear that Zia had decided to hinge his regime on Islam, religion unleashing very reactionary forces in the country.

Many of us were in in college during 1969 anti Ayub uprising and some had taken part in street. Bhutto’s era gave us some space to engage in collective social, economic, and political activities. Rigid and conservative social mores had started to accept more individual choices. Zia’s era brought us back to military rule plus forced religious orthodoxy. It was real hard not to be affected by this even if one was not political in any meaningful way.

Those of us connected with the campus felt regime’s Islamization and its attendant coercion even more forcefully. Increasing fascists tendencies by the right-wing student wing, frequent military backed raids on our hostels searching for ‘subversives’ convinced us that an era was finishing. It coincided with our own transformation from student years to those worrying about jobs. Many like myself decided for exile in form of foreign education and/or job. Few like Jamil Omer chose to fully engage engage in serious commitment to the working classes of the country.

But even when Jamil got into radical politics in late 1970’s he kept it mostly to himself. There was a whiff of something bigger about him though. Something bigger something radical that he was involved in. Later it became clear that he was being professional political activist. He was clear that the kind of radical politics he was working for meant antagonism with those in power. He probably had calculated the risks involved in engaging such discourse. And whereas he was willing to pay the price he did not want his friends to get in trouble as well.

Regardless of his political commitments, he remained very loyal to his old friends and would not want to miss any opportunity for a get together with his old buddies.

He hated bragging. About the only time I caught him bragging was not about himself but about ME !!. That was when I first met his Tajik-Afghan wife Nafeesa in 1990’s at my sister’s house in Islamabad. He will not stop recounting the story of how after years of no communication from the outside world, one day his jailers brought him a sack full of greeting cards and letters from the US. At this point of narration his body would do full theatrics – his eyes fully dilated, expressing surprise and pleasure of the moment, his hands in full swing indicating how enormous was size of the sack. He was sure that I was among those behind that extraordinary effort for his friend. Embarrassingly I did remember that around 1983 I was among the founding members of the Amnesty International’s local chapter at Texas University. The AI had already adopted Jamil a prisoner of conscience. All I did was to suggest our local AI chapter to start a campaign of sending the prisoner good wish cards and letters. And then again same happened at Agha Khalid Saeed’s small apartment at Durant Ave. in Berkeley sometime in the fall of 1983-84. As usual Agha had an usually large gathering of Pakistani students. News of Jamil Omer’s incarceration along with that of Tariq Hassan, torture and worse were heavy on our minds. Besides discussions and exchange of news it was decided to organize big letter/card writing campaign to our friends in Pakistani jails.

During his university years Jamil’s life was full of non-academic activities as well. Later in his life at least one never heard him talking about such activities. His decision to move to Lahore I believe was both political and personal. Lahore was natural choice for grass root political activities. I feel that Lahore also invigorated him at personal level. The move probably distanced him from his wife Nafeesa. She probably remained and felt a foreigner in Pakistan. And Islamabad was the limit to which she felt forced to give concession to her foreignness. I do wonder if Lahori proclivities to street culture, its spicy and but unhealthy culinary and its frank, and at times its linguistic obscenities made her feel further alienated.

And I think that Jamil did make some effort to live in Islamabad. He stayed there for several years after his jail years and those he spent in Afghanistan. I remember having met him at his huge E-11 house that he was using partly as residence and partly as a software outsourcing joint that he had built. One can imagine that he was trying to balance his political life with his career and his domestic life. Despite years wasted in jails he fully succeeded in heading a software outsourcing work that needed working with his clients in UK.

All this Lahori-ness was essential for Jamil’s mental well being I think. That was perhaps only concession he ever demanded of his personal life. Possibly he needed that zest of Lahori street life. Islamabad after all creation of a bureaucratic effort to construct a completely new town. To some degree it remains artificial, inoculated from real life, at the best a controlled experiment in Pakistani social/cultural life. Islamabad may be good for traditional Party power brokers – exactly the kind of politics he hated and the reason he wanted a real proletariat party. That kind of grit is only possible in a city like Lahore. That is where the Railway and post office unions were, where stalwarts like Faiz and Manto first cut their teeth. It was physically, socially, and culturally too isolated and unsuited for the political Jamil had chosen. It was also the city where his siblings and the larger family lived.

Still I had a strong feeling that rather great deal of time and energy was spent in just convincing various leftist political entities (ek Tangay diyan Sawarian in Lahori lingo) to get united and to give up their petty ideological differences for a bigger cause.

I doubt if he Jamil ever had Faiz’s dilemma of what Faiz called کچھ عشق کیا کچھ کام کیا. During his early youth, Jamil fully enjoyed and loved all that a student’s life can afford besides classroom – zest, adventurism, fun, and yes that falling in love experiences that are privilege of a youth. Later when he decided to use his life in radical politics he indulged in it as fully without regrets or looking back. Again, to quote Faiz:

جو چلے تو جاں سے گزر گئے

His friends lost a ‘beeba dost’ and the workers and underprivileged masses lost a very Beeba Banda.

Jamil Omar – Indomitable Fighter – Rest in Peace

Jamil Omar – Indomitable Fighter – Rest in Peace

Pervez Hoodbhoy

It was late 1979 – or maybe early 1980 – when I first met Jamil Omar. You could right away see that he was someone unusual. With intense, sparkling eyes and a determined chin, this young man had just returned from Romania and joined Quaid-e-Azam University as a junior lecturer in the computer science department.

Jamil Omar’s revolutionary road

Jamil Omar’s revolutionary road

Aamir Riaz

Jamil Omar was a committed soul. Born on August 1, 1952, he was grandson of Khalifa Nooruddin who earned great respect not only in his community but also among the intellectual elite of the early 20th century in our region. Like his grandfather, Jamil had the courage to carve his own way. Yet he was well-aware of the Nooruddin family legacy and lineage scattered from Bhera to Lahore.

Dada Amir Haider Khan: An Indian Che Guevara

Dada Amir Haider Khan: An Indian Che Guevara

Jamil Omer

While he lived, Dada Amir Haider Khan struggled to change the course of history, now in death he would have us change our view of it. Dada surfed the crest of change all over the globe during the first half of the twentieth century, which makes a simple account of his life read like contemporary world history.