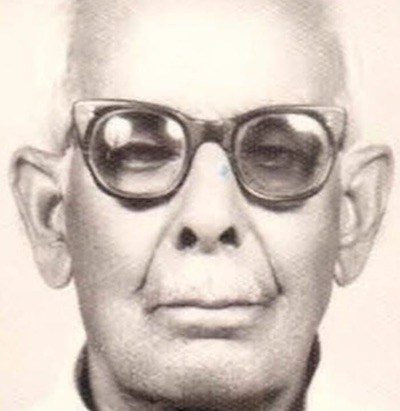

Dada Amir Haider Khan: An Indian Che Guevara

Jamil Omar

Dada Amir Haider (1900-1989)

Prof Jamil Omar (1952-2014)

While he lived, Dada Amir Haider Khan struggled to change the course of history, now in death he would have us change our view of it.

Dada surfed the crest of change all over the globe during the first half of the twentieth century, which makes a simple account of his life read like contemporary world history. The account is so reliable and close to life that that it should prove a major primary source for scholars of history and politics. For political activists who have carried on the tradition bequeathed by Dada, the account is essential reading for a critical understanding of their own past.

His life

So little is known about Amir Haider Khan’s very full life that it seems appropriate to start by presenting a very brief overview:

- 1900 born in a remote village in Rawalpindi district. Orphaned at an early age, put in a madrassah. Escapes to Calcutta, brushes with the underworld handling Afghan opium.

- 1914 joins British merchant navy in Bombay. Observes at close hand the dilemma of Muslim soldiers in the British army fighting their Turkish brethren in Iraq.

- 1918 jumps British ship in New York. Joins American merchant marine. An Irish nationalist, Joseph Mulkane, introduces Dada to anti-British political ideas.

- 1920 meets Indian Nationalists and Ghadar party members in New York. Starts distributing ‘Ghadar ki Goonj’ to Indians in seaports around the world.

- Passes the exam of Assistant Second Marine Engineer.

- 1922 dismissed from ship after the great post war strike. Works and travels inside the USA. Boiler engineer with the Pennsylvania Railroad. Airplane pilot. Autoworker in Detroit. Political activist, works with anti-Imperialist League and the Workers (Communist) Party of the USA.

- 1926 sent by the American party to the Soviet Union to study at the University of the Toilers of the East.

- 1928 completes the University course in Moscow and arrives in Bombay. Establishes contact with Ghate, Dange Bradley, senior communists in Bombay.

- March 1929 escapes arrest in the Meerut Conspiracy case and makes his way to Moscow to inform the Communist International (Comintern) on the situation in India and seek their assistance.

- 1929 arrives back in Bombay, meets and briefs B. T. Randive.

- 1930 Dada’s connection in Bombay with the Comintern turns informer. Dada rushes to Moscow to apprise them of the development and devise alternate plans. Attends the International Trade Union (Profintern) Congress as member of the presidium, also attends the 16th Congress of the CPSU.

- 1931 returns to Bombay. Sent to Madras to avoid arrest as still wanted in the Meerut Conspiracy case. Carries on political work all over South India under the pseudonym of Shankar. Sets up the Young Workers League.

- 1932 arrested by British for bringing out a pamphlet praising the Bhagat Singh Trio.

- 1936 transferred from Madras to Muzzafargarh jail, then transferred to Ambala jail.

- 1938 released. Starts open public political activity in Bombay. The Congress left elects him to the INC Bombay Provincial Committee. Attends the INC Annual General meeting in Ramgarh, Bihar.

- 1939 rearrested as Second World War breaks out. Interned in Nasik jail where Dada writes the first part of his memoirs.

- 1942 last of the Communists to be released after People’s War thesis. Trade Union work in Bombay. Attends the Natrakona (Mymansingh) All India Kissan Sabah in 1944.

- 1946 arrives in Rawalpindi on the eve of Pakistan to look after local party work. Organises a network to hide and safely repatriate Hindu families during the partition riots.

- 1949 arrested from Party office Rawalpindi under the Communal Act. Released after 15 months. Rearrested after a few months from Rawalpindi Kutchery for organizing the defence of Hassan Nasir and Ali Imam. When Liaqat government launches the Rawalpindi Conspiracy case Dada moved to Lahore fort and imprisoned with Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Fazal Din Qurban, Dada Feroz ud Din Mansur, Kaswar Gardezi, Hyder Bux Jatoi, Sobo Gayan Chandani, Chaudhry Muhammad Afzal, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Zaheer Kashmiri, Hameed Akhtar etc. Released after campaign in Pakistan Times and Imroze, but restricted to his village. Shifted to Rawalpindi when Dada seen influencing the military jawans from his area.

- 1954 Bogra [Prime Minister] to appease his masters in USA bans the Communist Party of Pakistan on 24 July

- 1954 Dada arrested later bailed out by Mohammad Ali Kasuri.

- 1958 Ayub imposes martial law. Dada arrested interned in Rawalpindi jail with Afzal Bangash, Kaka Sanober and other comrades from the Frontier Province.

- 1970s and 1980s Dada spends his twilight years in Rawalpindi. Donates his land and with his own labour builds a Boys High School in his village, then builds a Girls School together with a science laboratory. Gets them approved and hands them over to the Government.

- 26 December 1989 Dada passes away.

The striking fact about the above chronology is that Amir Haider like Flash Gordon had an uncanny knack of being at the right place at the right time. But the analogy ends here. Flash is a fictional character representing the Imperial British, Dada was a real life adversary of Imperialism who fought the British with such skill and tenacity that American professors Overstreet and Windmiller were forced to admit that “Amir Haider Khan was the most dangerous individual in British India.” Throughout his life we see Dada, the born rebel, standing up against injustice and fighting to better the human condition. While Britannia ruled the waves, Dada fought for the rights of the Indian seamen working deep below the decks. When the sun did not set on the British Empire, Dada risked his life to distribute banned Ghadar Party literature to Indians all around the globe. As the new world started to prevail, Dada, a naturalized American at the age of twenty, learnt and struggled against the system from within – as an International Workers of the World activist, as a working class family member, as a hobo, as a Klu Klux Klan victim, as an avid reader of Popular Mechanics and Scientific American and builder and flyer of airplanes, as a political activist working closely with the great Agnes Smedley and much more. When the world was shaken by the great socialist revolutions, Dada, now a full member of the Bolshevik party in Moscow, was closely following on detailed maps the march of Chou En Lai forces towards Shanghai. And during the golden hour of the Indian freedom struggle, Dada almost single handedly broke the political isolation imposed upon India by the British. Despite being on the British most wanted list, Dada using different pseudonyms and covers carried on political and organizational work in various parts of India. Work, for which Dada is still loved in Rawalpindi, revered in Bombay and worshipped in South India.

Dada was an international revolutionary – a Che Guevara of another age and on a bigger stage. He met and worked closely with some of the greatest socialist leaders of the twentieth century, which included besides others Thomas Mann (Engles’ student), Rosa Luxemburg (German revolutionary), Clara Zetkin (German women rights activist), Karl Radek (leader of Communist International), Liu Shao Chi (later president of China), Agnes Smedley (American anti-imperialist), Ralph Fox (historian who died resisting Franco’s march to Madrid), Piatniski (secretary to Comintern and Stalin) and nearly all the leaders of the Indian freedom movement. Dada’s steadfast struggle for freedom earned him the respect of Indian nationalists from the Andaman Islands to Peshawar, from gentlemen members of the parliament to Naujawan Bharat Sabah revolutionaries.

His memoirs

Writing with revolutionary responsibility, Dada is careful not to wash any dirty linen in public. Like a true Bolshevik, Dada chooses to maintain public silence on issues where he disagreed with the official Party line. On the face of it this should make Dada’s memoirs politically anodyne. But Dada’s actions were anything but politically neutral and they speak for themselves. ‘Dada’ may be an honorific title in Pakistan but in Bombay it was applied to Amir Haider Khan and others to denigrate them as obstinate seniors, for these ‘foggies’ doggedly waged inner Party struggle against political opportunism. It is also rumoured that Pakistan provided the new generation of comrades in Bombay with an excuse to shunt Dada from Bombay to Rawalpindi. Yet Dada’s memoirs are a testimony that he remained faithful to Party discipline to the very end of his life. Even in his rumblings as an old man he was careful not to insinuate against some of the old comrades or the People’s War thesis or a host of other issues which clearly troubled him. However, a close reading of the memoirs reveals that even Party discipline could not compel Dada to distort or deny facts. For example, Dada, the main representative of the Third International (Comintern) in India, puts it on record that on the China question Trotsky was correct and Stalin wrong; he criticizes M. N. Roy, who has since been rehabilitated, of fiscal irresponsibility and S. A. Dange, who has since been debunked, of weak character. It is perhaps on account of such ‘deviations’ that Dada’s memoirs nearly got suppressed. Once by our own publisher of Baluchistan insurgency fame – although this may well have been the far worse crime of sheer irresponsibility; and once by the CPI press – which on the face of it appears to be a more deliberate act of indexing. But thanks to the untiring zeal of Dr. Hassan Gardezi, the memoirs’ editor, Dada’s invaluable autobiography has finally been preserved for posterity.

The memoirs in themselves are a straight forward narration of events, however, delayed availability of such rare and authentic material is bound to reopen many debates. A critical study of the memoirs would go a long way in helping us better understand and appreciate our past. Even a non-critical reading like the present one, sparked a number of politically relevant questions. I would like to briefly take up a few of these here.

Muslim demagogy and Pakistani Hagiography

Hagiography prefers to ignore rather than explain inconvenient facts. The mainstay of our local brand of hagiography is that Pakistan was created for Islam. However, our hagiographers have never bothered to explain that if so, then how come the Pakistan movement was led by modern secular Muslims and supported by the Communist Party while mullahs of all callings opposed it tooth and nail.

Another enigma for local hagiography is the Khilafat Movement. Khilafat Movement based on pan-Islamic demagogic sentiments was popular among urban Muslims for a brief period towards the end of the First World War. But with its fantastic scheme of Tark-i- Amwaal and Hijrat it violated the interests of propertied Muslim classes. The propertied Muslim classes, for their part, were always more attracted to the option of a separate homeland where they could pursue their economic interests unhindered by the dominant Hindu bourgeoisie. Hence it comes as no surprise that while the Khilafat Movement was befriended by the Congress, it was vehemently decried by Jinnah. Pakistani hagiography has long taxed itself to square the Muslim demagogic Hijrat Movement with its exact opposite, that is, the Pakistan Movement. The hagiographic compromise is to gloss over the unsavoury details of the Khilafat Movement while awarding Bi Amma’s sons the status of national heroes.

Dada’s memoirs clearly reveal the true nature of the Khilafat movement. In Bombay its support lay in the Urdu speaking Muslim mill workers in Madanpura, who were the descendents of ruined hand weavers of Bihar and UP. The Khilafat newspaper openly incited these Muslims to violence when Hindu-Muslim riots broke out in Bombay but with typical demagogic irresponsibility it blamed the Communists. This service must have been well appreciated by Khilafat’s bourgeoisie friends in the Congress, who watched with glee the fall of support for the fledging Red Flag Worker’s Union amongst Muslim workers and were keen to employ them as strikebreakers.

The Khilafat demagogy also ruined the poor Muslim Mopla peasants of Malabar. Muslim Mopala peasant’s under the influence of Khilafat demagogy left their lands and chose to migrate to Afghanistan. Like most muhajirs they were simply herded back by the Afghans. But on returning to Malabar they found their lands occupied by Hindu landlords. What ensued was a full-scale civil war in which thousands died and even more were herded like animals into prisons. Dada through his historic jail struggle succeeded in winning for these poor and illiterate Muslim prisoners decent living conditions.

Hagiography not only glosses over the crimes of yesterday, it makes us perpetrate new ones today. The truth of this aphorism is vividly demonstrated by the fact that while the Khilafat leader Mohammad Ali Johar is remembered through a prestigious Society in Karachi and a modern Town in Lahore, all trace of Dada Amir Haider Khan, the greatest of Indian Muslim freedom fighters, has been conveniently removed from our official history.

The conspiracy of conspiracy cases:

‘Divide and Rule’ may well have been the first rule of British Imperialism, but ‘give the dog a bad name and hang him’ was a close second. The second rule was repeatedly employed by the British against the Communists in the guise of Conspiracy Cases. During the 1920s British attempted to crush the nascent Communist Movement through a spate of Conspiracy Cases such as the First Peshawar Conspiracy Case, Second Peshawar Conspiracy Case, Moscow Conspiracy Case (in all these cases Soviet trained Muslim Communists were the main accused); the Cawnpore Bolshevik Conspiracy Case (local Communists main accused); Lahore Conspiracy Case (Bhagat Singh main accused), the Meerut Conspiracy (Dada Amir Haider one of the main accused).

Fortunately the outcome of the conspiracy of conspiracy cases seems to be determined by the Toynbee ‘Challenge-Response’ rule. Weak movements are destroyed by it while strong movements are strengthened by it. The Meerut Conspiracy case singularly backfired thanks to Dada’s efforts on an International scale, which resulted in Meerut solidarity campaigns all over the world. For its part the Communist Party of Great Britain put up Shaukat Usmani, who was a prisoner in Meerut, as its candidate in the 1931 general election for St. Pancras South East. The candidature of Usmani was aimed by the CPGB to ensure freedom for India, and to highlight the plight of the Meerut prisoners. In this election, the communists polled seventy five thousand votes.

After Independence, this Imperialist conspiracy of conspiracy cases was continued by the government of Pakistan, with Liaqat Ali Khan launching the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case to counter the growing influence of the Communists.

Remote controlling revolutions

International movements never make successful local revolutions. The business is far to complicated to be successfully managed remotely. In his memoirs Dada, however, is of the view that had the Comintern trained and assisted the Indian communists on the scale it assisted the Chinese, he and his comrades could have built a strong United Front with the Congress and developed the Satyagarha Movement into a genuine revolutionary movement. But the facts as related in his memoirs show that the Comintern was unstinting in its assistance to India, the problem lay in more objective realities.

Perhaps the most valuable lesson hidden in Dada’s memoirs is that revolutions are made locally not remotely. Culled from the memoirs, here are some of the reasons why:

- Priorities may change in the remote location. For example, under Lenin Central Asiatic Bureau of Comintern set up in Tashkent a school to train the Khilafat Movement muhajirs drifting in Central Asia into an Indian army of revolutionaries. However, the Indian Military School was closed in April 1921, as a quid pro quo for industrial assistance that Britain promised to Soviet Russia, under Anglo-Russian Trade Pact in March 1921.

- Stalin in 1943, to appease Roosevelt and Churchill, dismantled the whole Third International.

- Local political complexities cannot be fully determined from a distance nor can foreign representatives be relied upon to come up with correct on spot remedies. Comintern’s role in the Chinese revolution provides many examples of how the best of International intentions can create serious local problems. During the united front period the great debate in the Comintern regarding China was whether to launch the agrarian revolution or not. Trotsky as member of the Comintern Executive Committee proposed the immediate launching of the agrarian revolution in the countryside, however, the majority led by Stalin rejected Trotsky’s thesis on the ground that launching the agrarian revolution at this stage would split the National United Front and would throw the reactionary Kuomintang leaders into the imperialist camp. But when America and Japan got directly involved, split in the United Front became inevitable and saving the lives of the communist cadres became top priority, M. N. Roy, Comintern’s representative in China, bungled the situation by disclosing confidential instructions to the left wing of the Kuomintang, with the result that Kuomintang moved swiftly to liquidate all Communists they could lay their hands upon, more than 5000 were executed in Shanghai alone.

- Promotes Embassy Socialism: Reliance on material or intellectual assistance from outside weakens local confidence and resolve. In the long run it promotes a degenerate political culture that serves the interest of the foreign embassies (and donors) and not of the local masses.

Epilogue

Commenting on Dada’s quiet passing away the local press reported that “He lived and died virtually unsung. That did not diminish him. It makes the rest of us look more small.” One hopes that with the publication of Dada’s memoirs he would be better known and the long conspiracy to deny and defame him will come to an end. For this little known Indian Che Guevara is yet to take his rightful place in the pantheon of twentieth century revolutionaries.

Jamil Omar

Chains to lose, life and struggles of a revolutionary : memoirs of Dada Amir Haider Khan

Chains to lose, life and struggles of a revolutionary : memoirs of Dada Amir Haider Khan

Edited by Hasaan N. Gardezi

Dada Amir Haider, for my generation, was a legendary figure. He was often mentioned in admiration by the elders that I looked up to and his name aroused much curiosity. But other than oral references and anecdotes no adequate account of the man and deeds were available in black and white.