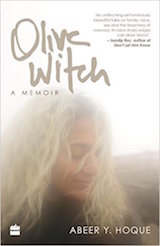

Olive Witch: A Memoir

Abeer Y. Hoque

|

I’m still a little bit in love/with everyone I’ve ever loved.” As someone who acknowledges, somewhat shamefully, that she is not a poetry person, these two lines from Abeer Y. Hoque’s The Lovers And The Leavers, an artistic mesh of stories, poetry and photography, continue to resonate seven months after I read the book. The rawness and lucidity that power those lines were reinforced again in Olive Witch, an all-heart and all-warts memoir, an intrinsically personal form that also works as a cutting-edge meditation on identity, self-actualization and the power of language. Olive Witch is about everyone Hoque has ever loved. It is also about the despair that descends despite that love, an unremitting, irrational depression that draws a curtain across all that is bright and comforting about the world. As much as Olive Witch brings to life the frangipanis in Nsukka, the freedoms of the US and the familial belongings in Bangladesh, it is the third-person interspersed accounts from a nameless, faceless psychiatric ward following a suicide attempt that is the dark heart of the book, simultaneously centring it and setting it free. But perhaps we go too fast (or perhaps not, because Olive Witch opens in the ward, as “she awakens slowly”). Narrated largely chronologically and heightened by notes on the weather and snatches of poetry, the book is broken up on the basis of the three continents where Hoque has lived, none of which she finds herself able to unequivocally call home. In Nsukka—the same university town where Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie grew up (eerily, Ngozi was Hoque’s Igbo name for herself as a child)—we meet the young Abeer, the eldest offspring of her academician parents, her sister Simi, a few months her junior, and their brother Maher, the baby of the family. An anecdote from these pre-teen years sets the tone for the balance of memory and forgetfulness that is Hoque’s most crucial resource for this book. An uncle comes to visit, bringing clothes for the children. Abeer and Simi wear the same size but, after the uncle’s departure, the two girls fight over dresses, each claiming the orange one to be hers. “We go on like this until I bully Simi into agreeing with me. This is nothing new. As the oldest, I have been getting my way for seven years now.” Later, Abeer comes across a photo of the uncle’s visit; she is in the red frock and her younger sister is in the orange one. “In that moment,” Hoque writes, “I realize memory is a treacherous thing.” Hoque, however, is no unreliable narrator: What she is, is a poet who writes prose. Which is why her memoir is no diary, but a finely crafted string of memories, each gem picked and polished to reveal its most eloquent facet. The songs and dances at home, the schoolyard racism, the sadistic teacher, the timid paedophile, the breaking of rules and the snapping of a long-stemmed rose—they all come back with the force of multiplied distance, each possibly more significant in retrospect than in the moment. With the onset of teen-age and the move to the US, the unarticulated alienation of the early years gives way to an urge to fit in. The usual adolescent front lines are weighted further by subcontinental parental expectations in every area from academic excellence and religious conformity to social rituals and prospective partners. University brings relief, her first serious relationship (Olive Witch is his name for her) but also a half-hearted PhD programme on decision theory at the Wharton School of Business. “When I started college, I was far away enough from my Nigerian childhood to leave it unspoken. Bangladesh came up only because of my skin colour…. I assembled my American accent, my assured American attitude and conjured who I thought was the perfect person, someone who was bold and whimsical and passionate. I climbed into her skin and wore it until it was mine.” The moulting, when it happens, isn’t pretty—after the psych ward and the abandoning of the doctorate programme comes a literal shearing (her wild, curly hair has always defined Hoque)—but on the other side, finally, stands a writer. The Lovers And The Leavers received positive reviews but it is Olive Witch, this startling and sharp, lyrical and lacerating, honest and uncompromising account of a rebirth, that marks Hoque as a major talent. Sumana Mukherjee | Mar 04 2016 | Live Mint

|

Paperback: 256 pages

Paperback: 256 pages