Khwaja Ahmad Abbas

|

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas (7 June 1914 – 1 June 1987), popularly known as K. A. Abbas, was an Indian film director, novelist, screenwriter, and a journalist in the Urdu, Hindi and English languages. He was the great grandson of the great Urdu poet and social reformer Khwaja Altaf Husain ‘Hali’. His column ‘Last Page’ holds the distinction of being the longest-running column in the history of Indian journalism. The column began in 1935, at Bombay Chronicle, and when it closed, it moved to the Blitz, where it continued till his death in 1987. He was awarded the Padma Shri in 1969, by Government of India. He had his early education till 7th in Panipat. Abbas completed his matriculation at the age of fifteen. He did his B.A. with English literature in 1933 and LL.B. in 1935 from Aligarh Muslim University. Abbas began his career as a journalist, when he joined ‘National Call’, a New Delhi based paper after his finishing his B.A. Later, while studying law in 1934, started ‘Aligarh Opinion’, India’s first university students’ weekly during the pre-independence period. After completing his education at Aligarh Muslim University, Abbas joined the Bombay Chronicle in 1935. He occasionally served a film critic, but after the film critic of the paper died, he was made the editor of the film section. He entered films as a part time publicist for Bombay Talkies in 1936, a production house owned by Himanshu Rai and Devika Rani, to whom he sold his first screenplay Naya Sansar (1941). While at the Bombay Chronicle, (1935-1947), he started a weekly column called ‘Last Page’, which he continued when he joined the Blitz magazine. “The Last Page”, (‘Azad Kalam’ in the Urdu edition), thus became the longest-running political column in India’s history (1935-87). A collection of these columns was later published as two books. He continued to write for The Blitz and Mirror till his last days. Politically, Abbas was part of a generation who were cultured in socialist and communist thought and organizations, and who had to make sense of the vast changes taking place in their own lifetime, most dramatically focused before, during and after national independence. In the cinema he was part of a generation of song and scriptwriters who came from the area which later became Pakistan and who had much influence in 1950s Indian cinema, though they were never an organized movement. Like many Communist Party and other left participants in the Indian film industry, Abbas made commercial films and consciously brought in progressive politics. In August 1942 Abbas started writing his monumental novel ‘Inquilab’ in English but seven years later he had only completed 13 chapters of the book. When he finally completed the novel there was a struggle with the publishers who wanted the length to be reduced. In 1954 the book was translated and published in the former Soviet Union with a print-run of 90,000. A year later a German edition hit the book stalls there. Only thereafter a publisher in Bombay agreed to publish it in English after pruning it down by 150 pages and paid Abbas Rs. 800 as royalty for the book. In 1976 a Hindi edition was published and a year later Abbas published the Urdu edition himself. KAA’s short stories like those of his contemporaries were not without their fair share of controversies. Both “Ababeel” and “Ek Insaan ki Maut” caused a hue and cry not only the first time they were published, but every time they appeared in magazines. The latter, also published under the title “Sardar ji,” had the Sikhs up in arms and even dragged Abbas to the Allahabad High Court. Sarojini Naidu, Governor of United provinces (now Uttar Pradesh) called Abbas to her house and ordered him to read the story aloud to her. As he finished reading it he saw Sarojini Naidu wiping her tears with the pallu of her saree. After regaining composure she told the writer, “The story is very touching, but you are a fool! Is this the time (1948) to write such stories?” Abbas’ stories and dramas like his newspaper columns mirrored the lives and problems of the common man. The readers waited anxiously every Thursday all over the country, at newspaper stalls and railway stations, for Abbas’ “Last Page” first in Bombay Chronicle and later in the Blitz to know how Abbas interpreted a certain event in the country and the world. Some people tried to label Abbas as a communist or a socialist, but no label could apply to him because he nursed no hatred or jealousy with fellow humans which is a pre-condition for an ‘ism’ to succeed. Unlike most people, including his leftist contemporaries and friends Abbas had no lust for worldly possessions or honours. Neither did he nurse any ambitions. Just once admitted that he was a Nehruvian but hastened to add that Nehru was a politician and had to make compromises in life, while KAA had no such compunctions. |

Birth— 1914-1987

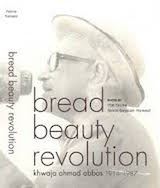

Birth— 1914-1987 Bread Beauty Revolution: Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, 1914-1987

Bread Beauty Revolution: Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, 1914-1987