Discontent and Its Civilizations: Dispatches from Lahore, New York and London

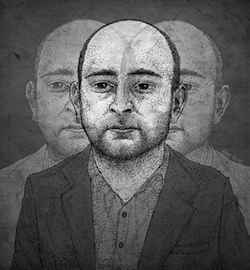

Mohsin Hamid

|

Unlike his three acclaimed novels to date, Moth Smoke (2000), The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007), and How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia (2013), Mohsin Hamid’s fourth book, Discontent and Its Civilizations (2014), is not a singular story whose action is firmly dependent on the dynamics of a particular (if undisclosed) geographical place. Rather, it offers a selection of dispatches penned for such publications as The Guardian and the New York Times during the preceding 15 years of the Pakistani writer’s nomadic or, to use his own metaphorically accurate epithet, “waterlily-like” experience of moving between Lahore, New York and London. The categories under which the essays in his new book are clustered: ‘Life’, ‘Art’, and ‘Politics’ may be deemed universal, and the subjects of these pieces are wide-ranging. Yet the non-fiction writings Hamid has produced in this period that drift from metropolis to metropolis nevertheless remain rooted — like their author himself — in the shifting soils of his home country. He may fantasise about having the freedom, in a globalised world, to invent himself “in that country, this city”, thereby “becoming a different person”, even a different kind of human. But the transnationalism of Hamid’s writings are — and, one suspects, will always remain — informed by a globally de-centred (if privileged) Pakistani perspective and, additionally, a growing interest in post-national collectivities and the utility of his country’s Asian interconnectedness. Discontent and Its Civilizations takes its title from a 2010 International Herald Tribune article of the same name. In it the writer expresses his dissatisfaction with “the idea that we fall into civilisations, plural”. For Hamid, this notion is “merely a politically convenient myth”: “Civilisations,” he asserts, “allow us to deny our common humanity, to allocate power, resources and rights in ways repugnantly discriminatory”. His introduction to the 2014 collection reinforces this point, warning that: “Civilisations are illusions, but these illusions are pervasive, dangerous and powerful. They contribute to globalisation’s brutality.” According to Hamid, the reality of these supposedly advanced sociocultural systems can be disputed. But the significance of their phantoms, in providing a justification for violence or excuse to clash, in curbing self-invention, and in denying the possibility of holding hybrid identities, cannot be dismissed. While the volume seems to foreground Hamid’s discontented or, at least, contesting stance vis-a-vis the general conduct of contemporary geopolitics, (and this remains a substantial theme), Discontent and Its Civilizations is not a treatise. Amongst the dispatches from the years 2000-2013 that it seeks to batch together are some more personal and ephemeral reflections which may now seem a little puerile, such as an early meditation on a trance event in Lahore where a veiled “woman introduced [him] to the pleasures of sweat”. Many other of the 15-year-old pieces, however, point to ongoing concerns, such as the hostile bureaucracy encountered by even the well-dressed Pakistani on attempting to secure a tourist visa to enter the closely guarded gates of Europe. Dressed in his “white shirt, blue tie, brown face, brown eyes”, his documents all in order, Hamid is both plagued by an uneasy awareness of the treacherous hint of a seemingly “fundamentalist stubble” he failed to shave from his chin, and ashamed that his deference to such sartorial norms “tacitly acknowledged an accusation [that he] would have liked proudly to ignore”. Here, his sentiments echo those of other contemporary writers (such as Kamila Shamsie) who, on account of their affiliation with the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, have been called upon, in the decade after the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Centre, to apologise in some measure for their anticipated guilt by association with a Muslim nation “deemed prone to poverty and violence” and thwarted by the spectre of Islamic terrorism. There are lasting insights into Hamid’s literary influences and the evolution of his novelistic approaches. Some of these essays underline the author’s concern with exploring how certain modes of address which can be used to implicate his readers both as “a sort of conspiratorial you”, and as judgmental, decision-making characters in his narratives. Essays such as ‘Pereira Transforms’, which appeared as the introduction to a recent translation of Antonio Tabucchi’s Sostiene Pereira, point to Hamid’s quite specific interest in exploring how “testimonial form[s]” can “seduce” his listeners into an “interpretative space” where they are responsible — as in the trial-like Moth Smoke and the teasingly faux-confessional The Reluctant Fundamentalist — for determining their protagonists’ guilt or innocence and, hence, their fate. Yet, as his 2013 Guardian article, ‘Enduring Love of the Second Person’, makes plain, Hamid’s interest in making co-created fiction does not come simply as a result of a desire to play novelistic games. Hamid remarks of his post-9/11 masterwork, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, in which a young Pakistani financial professional narrates for the entertainment of an implied American interlocutor the story of how he removed himself from New York to Lahore in the wake of the terrorist attacks: “I wanted the novel to be a kind of mirror, to let readers see how they are reading, and, therefore, how they are deciding their politics”. Hamid’s consciousness of the very real danger of powerful nations such as the United States projecting “stories of evil” on to the world’s “murky, unknown places [and peoples, which] are not blank screens at all” is long standing, as his prescient 2001 piece ‘The Usual Ally’ indicates. One of the particular attractions of Discontent and Its Civilizations, for those familiar with Hamid’s writing, is that it encourages us to look again at his growing body of work, personal and political, imaginary and reality-based. It seems almost to invite us to observe the overlaps and discontinuities between the political viewpoints and subject matter that preoccupy Hamid in his non-fiction writing, and the literary perspectives and techniques he deploys in creating his novels, from dramatic monologue to self-help narrative, or short, dystopian science fiction. (Compare, for example, his 2011 short story ‘Terminator: Attack of the Drone’ with his 2013 review essay published in The New York Review of Books, ‘Why Drones Don’t Help’). Of course, after reading this latest collection, one is left to fantasise and project a vision of what may come next for Hamid in terms of fiction; he mentions the potential advent of a fourth novel half-way through the selection. Given his frequent reference, particularly in his more recent dispatches (including ‘Fear and Silence’, published in Dawn in 2010), to the persecution of Pakistan’s religious and ethnic minorities — Shia, Ahmadi, Christian, Baloch — and his interest in probing the status of the supposed majority in a country variously “divided by language, religious sect, outlook and gender”, one might anticipate a novel that explores its “dangerous failure to bridge such divisions”, and the illusion perhaps of their unbridgeable nature. But we will have to wait, and see. Madeline Amelia Clements | 12 April 2015| Dawn

|

Mohsin Hamid

Mohsin Hamid