Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932)

“You need not be afraid of coming across a man here. This is Ladyland free from sin and harm. Virtue itself reigns here.”

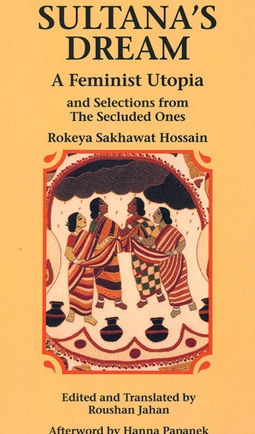

So says Sister Sara, one of the main characters of Sultana’s Dream, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s story about a feminist utopia, where men are banished and women reign supreme. Ladyland’s man-less world is one of light and beauty and laughter, without violence and without war; the rule of femininity is an end to fear. As the women of Ladyland say, “Men, we find, are of rather low morals, and so we do not like dealing with them.”

So says Sister Sara, one of the main characters of Sultana’s Dream, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s story about a feminist utopia, where men are banished and women reign supreme. Ladyland’s man-less world is one of light and beauty and laughter, without violence and without war; the rule of femininity is an end to fear. As the women of Ladyland say, “Men, we find, are of rather low morals, and so we do not like dealing with them.”

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain wrote the story in 1905, on an afternoon when her husband, a magistrate, was out for inspections of his territory. When he returned from his duties, he asked her how she had spent her time, and she handed him the story, written in English. The luck of having an educated husband who chose to respect rather than repress her penned rebellion blessed her. Sultana’s Dreamwas published in the Madras-based English Periodical The Indian Ladies Journal that same year.

With its publication, the silence of seclusion was broken by one who had lived its realities. In one short story, Rokeya rendered real the possibility of women being in charge, a reversal unimaginable in a reality steeped in male dominance. Her flight into fantasy was a revelatory one; in the details of a man-free world, the illogic of an existing women-free one was laid bare. Similarly shredded were the myths of superiority that sustained the seclusion of women: “Men have bigger brains,” the unbelieving visitor to Ladyland interjects to her guide. “An elephant also has a bigger and heavier brain,” is the response. “A lion is stronger than a man,” and yet neither dominates the human race. Bit by bit the lies and lassitudes of male superiority are taken to task, unraveled and handed back as formless, meaningless myths.

The messages in Sultana’s Dream are not meant for men alone. The men of Ladyland, used to their seclusion and sidelining, have become used to their own subjugation, uninterested in rebellion, obsessed with the cleanliness of their kitchens and the petty details of their invisible lives. In the condescension she heaps on them in Sultana’s Dream, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain is careful to underscore how the toleration of suffering enables its persistence. The women who bear it in silence allow the perpetuation of oppression and are complicit in its persistence.

In 1880, when Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain was born, few records were kept of female births. If those that have survived are indeed correct, then this past December 9, 2013, would have been her 133rd birthday. Since then, several countries have been created and then created again to corral the Muslims of the subcontinent into nationhood. Yet, all the currents and courses of political upheaval of more than a century have not been able to erase the core realities that propagated her rebellion. Countless daughters-in-law chafe against long afternoons spent tolerating the demands and dominations of their in-laws, while husbands, the magnetic centers that justify their existence, are away at work doing important things. The mechanics of seclusion, while altered, still dictate a relegation of vast numbers of women, many of them now educated, to the quibbles of kitchens and the dribbles of babies. There, their brains ferment and fester, to fit the moulds of expectations and constraints. Science, which is the pivot on which Rokeya Sakhawat Hussain imagined a reversal of patriarchy, has been unable to save them; the engineers and doctors and architects and nurses are all too weak to destroy the dictates of domesticity.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain died before the British left India, before Pakistan and before Bangladesh. An essayist, she wrote only the one story in English; the remainder of her writing was in Bangla, deigned for Muslim women. She sought not literary notoriety but social reform, and so she wrote to her own, to the reading women who were too afraid to speak or too tired or too lazy or who thought speaking out was futile or fruitless. She wrote to the women who believed that patriarchy was custom and tradition and often even religion, who thought that the way things had been was an argument for the way they must forever be. They would be proven wrong. Things did change, the British did leave, and not one but two countries were created. Then another one of them broke into a further two, as equations of faith and nationhood proved less than equal.

It was perhaps in the rancorous tumult of the breaking and making of nations that Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s word and vision was lost, at least to the bit of divided Empire that is now Pakistan. While the University of Dhaka boasts a Rokeya Hall and statues of her are said to dot the campus, no such commemorations or remembrances exist on this end of the Muslim subcontinent.

In this sense, the fact that she was Muslim seems unable to have saved her legacy; the burdens of having been Bengali and feminist, arriving fast and first, foist a deliberate forgetfulness. Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain had premonitions of this pettiness, for in entrusting affairs to men, she cautioned, women embrace in every respect a lesser world — less moral, less peaceful, and less beautiful than the one that would exist otherwise, that can be glimpsed for just a moment in Sultana’s Dream.