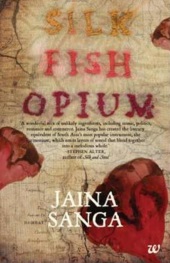

Book Excerpt: Silk Fish Opium by Jana Singa

Chapter 5

DRESSING FOR THE show, it had taken Rohini three tries to get her sari on properly, the pleats too wide or too narrow as she tucked the fabric at her waist. She was afraid her voice would freeze, or she would forget the lines, or worst of all, get the lines mixed up with some other song and disgrace Hanif in front of the whole college. She had hardly eaten all day, a mistake she now realized; her stomach was churning and gurgling in the most awful way as she looked at the drawn curtain and how the spotlights beyond burned though a galaxy of tiny holes. The array of microphones around the instruments made her heart lurch. “Does it change the voice?” she asked Hanif, who stood beside her backstage, humming, his head swaying gently from side to side. “Should I sing softer?” Without looking at her, he shook his head and kept humming. The tension among the dozen or so other performers only heightened her own.

DRESSING FOR THE show, it had taken Rohini three tries to get her sari on properly, the pleats too wide or too narrow as she tucked the fabric at her waist. She was afraid her voice would freeze, or she would forget the lines, or worst of all, get the lines mixed up with some other song and disgrace Hanif in front of the whole college. She had hardly eaten all day, a mistake she now realized; her stomach was churning and gurgling in the most awful way as she looked at the drawn curtain and how the spotlights beyond burned though a galaxy of tiny holes. The array of microphones around the instruments made her heart lurch. “Does it change the voice?” she asked Hanif, who stood beside her backstage, humming, his head swaying gently from side to side. “Should I sing softer?” Without looking at her, he shook his head and kept humming. The tension among the dozen or so other performers only heightened her own.

The giant curtain parted and she caught a glimpse of the crowded auditorium – hundreds of people dressed in their best evening clothes all cheering and applauding as the two of them walked on stage and into the blinding lights. The hoots and whistles from the back made her wish she had never agreed to sing in public. Hanif nodded to the sitar and tabla accompanists who were already at their positions on the far side of the stage. He seemed confident and composed, disconnected from the flourish of the moment. He smoothed his hands over his white sherwani and adjusted his vest before sitting down on the small carpet before the harmonium. She lowered herself onto the other carpet next to him, keeping her eyes down, nervousness clotting her throat.

Hanif played a scale on the harmonium. Sa-Re-Ga-Ma-Pa-Dha-Ne-Sa … and back again … Sa-Ne-Dha-Pa-Ma-Ga-Re-Sa. To Rohini the notes sounded both foreign and familiar. She adjusted the pleats of her sari around her knees. The house lights dimmed. In the audience, rustling and shuffling ceased. Hanif cleared his throat, leaned into the microphone and announced the title of the ghazal, first in Urdu, and then in English: “Jeena hé téré Muskurahat ké leeyea … I Want to Live Only for Your Smile.”

The slow, quiet notes of the sitar, the tabla, and the harmonium started the song, Hanif’s sonorous voice joining with the music and unfolding over the auditorium like yards of rich, luxurious brocade. Rohini’s tender contralto voice came in on Hanif’s cue, picking up the melody. His eyes were on the audience; his fingers moved on the keyboard with ease and grace. He caught a faint flowery scent from the gajra pinned in her hair. He could hear the light intakes of her breath, which the microphones would not detect.

Rohini wanted to look at him, to read some glimmer of approval on his face, but she didn’t dare; her gaze stopped at the window nearest the stage, at the shadow cast by the big tamarind tree. Her voice didn’t freeze, and she didn’t forget the words, and she didn’t get the lines mixed up with another song.

Something else happened.

She felt his voice passing over her, touching her skin like a vapor of cool mist, at first swirling unfettered around her, and then settling gently against her body. She felt his voice reaching into her, stimulating all her senses. The muscles in her neck grew taut with fear, joy, hesitation, delight. As their voices came together and the song picked up momentum, she gave her words to his. In the background, the beat of the tabla –taka-dhan-taka-dhan-taka-dhan-dhan – and with it, the reflective twang of the sitar. Together their voices refracted into myriad hues, his dipping into lower, darker, richer ranges, and hers soaring effortlessly to the higher, lighter, brighter registers.

She raised a nervous hand to adjust the gajra in her hair. Taka-dhan-taka-dhan-taka-taka-dhan-dhan – the tabla throbbed fast and loud.

He saw the white flowers, the petals wilting and turning brown at the edges. He saw her small wrist with the colorful bangles. He saw the semi-circular patch of perspiration under her arm and, a sliver of her midriff below the sari blouse. Underneath the blouse he saw an outline – the soft roundness of her breast.

During the final refrain, she sensed his eyes searching her face, pursuing her thoughts. Around them – taka-dhan-taka-dhan-taka-dhan-dhan – the tablas kept on. She glanced at Hanif. He smiled. It was a smile full of color, full of sparkling, tingling color; it was the kind of smile to hide in her fist and bring out to savor when no one was looking. Jeena hé téré Muskurahat ké leeyea – she would live for his smile. After the last line of the song, after their voices reached a crescendo and the final note of the harmonium gave way to resounding applause, Rohini closed her eyes in breathless, bewildered surrender.

* * *

At Chowpatty beach the next day, Hanif pointed to the farthest bench on the beach and said, “Let’s walk up to there. It’s about a kilometer. Are you tired?”

Rohini shook her head. Six o’clock in the evening; she should be on the train home by now. She would say she had to stay late for tutorials. They were in plain view of anyone driving down Marine Drive. She glanced at him, then quickened her steps and moved ahead. Did it look like they were walking together? She drew the end of her sari over her head, as though to shield herself from the sun.

“Wait,” he said, “Let me buy some channas.” He walked toward the channa-walla and she followed. She stood back as he spoke to the channa-walla. Hanif handed her the cones and she held them, the newspaper warm in her palms, and watched as he reached in his pocket for the coins. They walked in silence the rest of the way down the beach. He pulled out an un-ironed handkerchief and brushed the sand off the bench before they sat.

“The sun will be setting soon,” she said. “At Versova, the sunset is beautiful.”

“Oh, it must be a different sun over there,” he said, winking. “Your house is on the beach?”

“Yes. It was built by a British architect.”

“Like Buckingham Palace,” he said.

She laughed lightly.

“Do you have Changing of the Guard?”

“We do have two chokhidaars. The night chokidaar doesn’t do much; he sleeps most of the time.” She laughed again as he threw a delighted glance at her.

They ate the channas and sat in silence for a few moments.

“You looked good in your fancy sari yesterday,” he said. “I think the program was a success.”

“Was my voice alright? I was worried about the microphone.”

“Your voice was beautiful. You are beauti …” He stopped himself.

She knew what he was about to say. Her heart skipped and a fiery rush filled her head. The breeze lifted the end of her sari, and she let it slide off her head. Was he gazing at her? Curious about her own loveliness, she wanted to see herself sitting on the bench, see herself as he was seeing her. She looked straight ahead at the water, at the glowing sun that teetered teasingly on the very edge of the horizon. Gentle shades of red and orange stroked the sky. As the arc sank into the sea, the sky turned bright crimson and gold. Yes, this must be a different sun, because it was better than any sunset she had seen before.