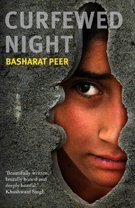

Curfewed Night: A Frontline Memoir of Life, Love and War in Kashmir

Basharat Peer

|

|

As a young student in Delhi, Basharat Peer used to feel a sense of shame each time he walked into a bookshop. There were books written by people from almost every conflict zone of the age, but where were the stories of his own homeland of Kashmir? Some could be found in the work of the great poet Agha Shahid Ali, but in terms of prose narrative there was nothing in English but “the unwritten books of the Kashmir experience”. Peer’s Curfewed Night is an extraordinary memoir that does a great deal to bring the Kashmir conflict out of the realm of political rhetoric between India and Pakistan and into the lives of Kashmiris. Peer was only 13 in 1990 when Indian troops fired on pro-independence Kashmiris and, as he puts it, “the war of my adolescence started”. It is a war that hasn’t yet ended, though it has changed shape considerably in the last 20 years. One of the strongest sections describes how it felt to be a young teenager swept up by a movement with “Freedom” as its cry. Peer writes of how all the embarrassments and failures of adolescence fall away when you join in a procession and feel yourself part of something larger; how the militants who crossed into the Pakistan-controlled part of Kashmir for guerrilla training would return as heroes; how “like almost every boy, I wanted to join them. Fighting and dying for freedom was as desired as the first kiss on adolescent lips.” When he was 14, Peer and his friends approached the commander of the separatist group JKLF and asked to be signed up. The commander laughed them away, and a few days later Peer’s family heard what had happened and intervened. The young Basharat came to an agreement with his father that he would wait a few years before deciding whether or not to sign up, and in the meantime he would study. Rebellions, his father pointed out, were led by educated men. But in the Kashmir valley, even the life of a student was fraught. “The fighting had changed the meaning of distance,” Peer explains. The six-mile ride from his school to home carried with it the possibility of being caught in gunfire or encountering a land mine. Military checkpoints were everywhere, and humiliation and abuse from the Indian security forces towards the Kashmiri residents was part of daily life. Many parents, including Peer’s, sent their sons away to finish their education far away from the valley. But in Delhi, as a student and then a reporter, Peer’s thoughts were never far from Kashmir. And finally he returned to the valley, no longer the naive 13-year-old but a reporter aware of all those unwritten books of the Kashmir experience. One of the great achievements of Curfewed Night is its seamless mingling of memoir and reportage. It is the book of Basharat’s Peer experiences, yes, but those experiences include returning to Kashmir and seeking out the stories of others affected by the conflict. It is a formidable challenge to tell the stories of Kashmir’s suffering without numbing the readers’ senses, and that Peer is able to do so is testament to his gifts and sensitivity as a writer. The chapter “Papa-2” discusses the notorious torture centre of that name which was eventually shut down and turned into the residence of a high-ranking government official. “Before moving in, the Oxford-educated officer called priests of all religion to pray there and exorcise the ghosts.” This sentence comes near the start of the chapter; we have not yet encountered the ghosts of Papa-2, but Peer is already telling us to prepare ourselves for the stories that will follow. Curfewed Night is filled with many such finely judged details, which quietly detonate on the page. One of the most moving moments in this very moving book tells of Peer’s inability to visit Kunan Poshpura, the village where Indian soldiers gang-raped 20 women in 1990. He sits at a bus-stop waiting for the bus to take him to Kunan Poshpura, but when it arrives he just goes on sitting, listening to the sound of the revving engine, and watching the bus drive away. For all the stories of suffering he seeks out, there is one he cannot bring himself to look at too closely. For the 13-year-old Basharat Peer of 1990, the heroes of the Kashmir conflict were obvious. As an older reporter, in an older war, he sees the damage inflicted everywhere. The war comes closest to home when a man with a personal grudge against his father convinces the militants that the elder Peer is the enemy; his parents narrowly escape a land mine intended to kill them. He also gives space to the Kashmiri Pandits (the title by which Kashmiri Hindus are addressed) who were forced to leave the valley when the fighting began. But he is not a writer who will fall back on the comfortable assertion that everyone wronged and everyone was wronged – the heart of this book is a demand for justice for the Kashmiri people, whose suffering at the hands of the Indian security forces has been beyond measure. At the end of Curfewed Night Peer crosses the “line of control” (the Indo-Pak ceasefire line which functions as a de facto border separating one part of Kashmir from the other). He writes: “The line of control did not run through 576 kilometres of militarised mountains . . . It ran through everything a Kashmiri, an Indian and a Pakistani said, wrote, and did. . . It ran through the reels of Bollywood coming to life in dark theatres, it ran through conversations in coffee shops and on television screens showing cricket matches, it ran through families and dinner talk, it ran through whispers of lovers. And it ran through our grief, our anger, our tears, and our silence.” Kamila Shamsie | 5 June 2010 | The Guardian

|

Basharat Peer

Basharat Peer