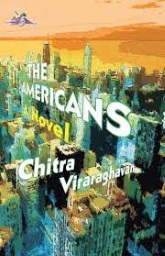

The Americans

Chitra Viraraghavan

|

|

The first reason why you would possibly pick Chitra Viraraghavan’s The Americans off a crowded book shelf could be its cover; it’s one of the best I have seen in recent days. As is my habit, I slipped the jacket off the hardback and propped it up where I could see it properly, then curled up with the pretty volume bound in yellow. The book is not too big and settles comfortably upon your fingers and palm when you lie back to read. Yes, this is a piece of diaspora writing alright, but thankfully it’s not about the angst of the third generation immigrant in a developed country. The diaspora we usually meet in books has plenty of money, a reasonably stable but unsatisfactory career or position and no real worries except about his or her identity. In The Americans we meet lives which are displaced for various reasons. The worries of the characters are pretty real. They are the doubts they experience under the swagger of success. You hear about a character as a brilliant student, but there’s something wrong with him you cannot pinpoint; then there are the lonely characters you meet on flights either going for or returning from a visit with oceans of stories in their eyes. Not all of them live in good houses, not all of them are welcome in their current worlds … and only some have escape routes which they want to take. The people in this book have the same problems as any of us. One character doesn’t have children, another has too many and yet another has a child with a problem. Someone doesn’t want to go back home and there are some who can go back but won’t. Then there are parents who travel across the ocean to see their kin, and elsewhere a mother is told by her son she will never see him again and who dies without being able to. Perhaps one character that keeps the reader’s attention through so many lives is Tara. She travels to the US to be with her niece, while her sister takes her nephew to a medic at another location. The lonely widowed gentleman she meets on the flight is not visiting out of his own choice; he is only obliging his daughter by doing so. The disjunctions the book deals with are saddening. A student commits suicide, a techie gets paranoiac about a possible sinister plot within the system, an illegal immigrant couple has no address they can pass on to their employer, the legal immigrants who are their employers cannot cope with being themselves, a victim of human trafficking dies but another is rescued. There are older, sadder lives and younger uncertain ones. Not all the people we meet are Indian. There are glimpses into the lives of Mexican, Hispanic and Israeli immigrants. I found it curious that here the Indians are on the side that can arrogantly suggest how to live better. They are almost real Americans. The author, thankfully, makes no deliberate effort to be literary. There is no premeditated style clogging your reading pace. Nor is there an existential problem depressing you. An interesting experiment with the structure of the book also has my applause. One of the characters, an immigrant student, exists across the book entirely through her notes. And another’s paranoia is presented in a different, darker font that raises your pulse. But at some places I found vocabulary that hindered my reading. Why should a character ‘have a conniption’, when he could have ‘hysterics’ or a ‘fit’? I also thought the book could have done with finer editing. But now I am dangerously near nitpicking, which I have no mind to do because I did enjoy the book. I read it at one go in half a day because I felt the pull of the incomplete story each time I put the

|

Chitra Viraraghavan

Chitra Viraraghavan