Cafe Le Whore

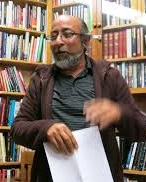

Moazzam Sheikh

Paperback: 122 pages

|

It is difficult to decide which facts of an author’s life are relevant to a book review. A lot of reviewers have already made a big deal of the fact that Moazzam Sheikh is a Pakistani immigrant living in the USA. An equally important fact is that he is a trained librarian working at a public library in San Francisco. That makes the author, at least professionally, an ally of Borges, perhaps the most famous librarian in contemporary world literature. The alliance is not only professional. The affinity seems to be operating in the way both of them choose their themes and events and symbols they use in their fiction. Sagheer Malal once described Borges as “a writer who produced literature for other writers.” This also seems to be the case with Moazzam Sheikh’s book Café Le Whore and Other Stories. The second collection of short stories by Sheikh is a book that breaks almost all the conventions of narration without properly falling into the readily available category of “magical realism.” A potpourri of irreverent, logic-defying, quirky and melancholic short stories, the book should have been available more widely all over the world even if just as a counter-argument to what is being celebrated as mainstream Pakistani literary fiction in English. Moazzam Sheikh writes an uncensored voice and describes, without hesitation, what other writers do not even dare to think when alone. For example, the title short story of the book is about a mother who dies in Pakistan but chooses to visit her son in San Francisco from the grave. She is not a ghost because she can complete perfect transactions and order coffees and croissants in a café where transvestites, homophiles and other marginalised figures hang out. The Café Le Whore is owned by a transvestite or transgender Lahori, ostracised by his family. The story becomes a meta-fictional story because the narrator discusses other ghost/return-from-the-dead stories with his mother. The erstwhile dead mother now also discusses metaphysical concepts in a dismissive way; “There is no meta-sheta for the dead.” The dead mother later seems to have transformed herself into a prostitute but that is almost as confusing as her reappearance among the living and her musings on the living and the dead and those who are stuck in-between: “You know many dead souls metamorphose into writers.” To make matters meta-meta-fictional and self-referential, the narrator also discusses an upcoming issue of an online South Asian literary magazine with his dead mother: “How about if I turn our interaction into a fictional piece? Would that bother you?” The non-ghost returned-from-the-death mother does not mind if the story is told as fiction but she minds it if the story is told as true. She seems to have developed a more assertive self after her death. Her pre-death self was suffering from dementia and had become very absent-minded. In another short story, the library is the setting where another kind of ghostly being is acting her will. An elderly lady seems to be living among the books and she is especially fond of a book titled The Great Miscasts. The librarian also happens to be a diarist who buys the book of a Pakistani American author. The book is titled The Idol Lover and Other Stories Moazzam Sheikh’s first collection of short stories. It is a strange story-world: the fictional characters are buying actual books written by the author who is writing the fiction and he also happens to be discussing the possibility of writing fiction about improbable encounters with neither-dead-nor-living beings and non-ghosts. The fictional world of Sheikh is a perfect example of a human lebenswelt, which seems to have been conjured up by language. We are the only species that has dictionaries and encyclopaedias and voluminous chronicles of history. There are about 130 million books written by us containing around 2 trillion words (according to the 2010 estimate by Google Inc.). Of course, we have to produce and consult some ghostly creatures to become so verbally productive. The book is not only a good example of meta-fiction, among other things, but also a meta-publication. There is a 2011 interview on a South Asian literary website in which Moazzam Sheikh is discussing that he should not publish his own book through his own publishing house Weaver Press. But that is what he did in 2013. But this is not a vanity publication. It appears to be a part of a wider trend. A large number of writers are feeling that publishing world is not taking care of the interests of the writers and are establishing their own publishing houses. Dave Eggers started his own publishing house McSweeney’s after having become a celebrated author of a memoir self-reflexively and humbly titled A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Now his own publishing house negotiates the terms of his books with other mainstream publishers. Therefore, Moazzam Sheikh deserves all kudos for breaking all the established norms of fiction, publishing, promotion, and distribution. This celebration is not due to the fact that he is an immigrant writer who writes fiction but because he would have been a fine writer even if he had not migrated out of Pakistan. There are two things that may have happened to him had he chosen to stay in Pakistan: he may have become more self-censoring because of Pakistan’s Wahabization or he may have become extremely controversial. Saeed Ur Rehman | 23 March 2014 | TNS

Searching For Aunty Nimmi: An excerpt from Cafe Le Whore |

Moazzam Sheikh

Moazzam Sheikh