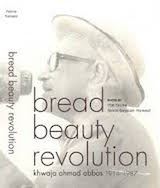

Bread Beauty Revolution: Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, 1914-1987

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas

|

Ahmad Abbas wore many hats and distinguished himself in each of the roles he chose. As a pioneer of progressive cinema, a consummate writer of short stories and novels that depicted the human condition and a committed journalist whose Last Page column acquired legendary status, he blazed new trails and fashioned his own path. Abbas was an important figure from a critical past. His body of work deserves to be studied and his life remembered by millennials and generations to come. This commemorative volume, a celebration of the man on the occasion of his 100th birth anniversary, arrives as a reminder of the humanism that characterised his life and work. Lavishly produced and deftly edited by Iffat Fatima, an independent filmmaker from Kashmir, and Syeda Saiyidain Hameed, the social and women’s rights activist, educationist and writer, this book from the Khwaja Ahmad Abbas Memorial Trust provides invaluable insights into his mind and personality. A man of many talents Despite his many talents, or likely because of them, Abbas could never be boxed into any creative category. And he was well aware of it. As Syeda Saiyidain Hameed informs the readers in her marvellous introduction to the compendium, Abbas himself would often ask his readers: “Who am I? Writers say I am a journalist; journalists say I am a film-maker; film-makers say I write short stories.” The editors of this volume, who recognised that the only way to appreciate Abbas fully is to study him in totality, have paid a perfect tribute to his oeuvre by dividing the volume into 10 sections that feature selections from his writings, focus on his cinema through his interviews and conversations, talk about his beginnings and early life and adventures, and reveal the man behind the mighty pen through reminiscences and tributes by actors and associates. The nature of the public adulation of Abbas also kept changing over the decades during which he was active. For one generation he was the man who collaborated with Raj Kapoor to unveil some of the finest examples of high-quality mainstream Indian cinema, such as Awara and Shree 420, while another celebrated him as the writer of powerful and poignant stories such as Sardarji, a lamentation of the violence and mayhem the country witnessed in the wake of Partition. And much before Independence, his was a significant voice writing about the marginalised sections of society. Abbas slipped in and out of the many roles he had chosen to play with a rare finesse, much like a thespian. Abbas was fortunate to have inherited a long tradition of intellectualism and reformist ideals from both sides of the family. His mother’s grandfather, Maulana Altaf Husain Hali, was a poet who used verse as a tool against social evils and as an instrument of reform within the Muslim community. Abbas began carrying forward the torch early on, even as a college student, when he published Aligarh Opinion, a handwritten weekly newspaper that he personally peddled on a bicycle. This was the start of his life in journalism which would eventually see him pen one of the longest-running columns in the history of news in Blitz, a weekly tabloid founded by R.K. Karanjia. Reading the compendium is like taking a train journey back in time, to a world far removed from the present. Be it Abbas’ harrowing first-person account of what he saw in Calcutta (now Kolkata) during the Bengal Famine—which inspired him to make the groundbreaking film Dharti ke Lal (1945)—or his active involvement with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), his cinematic endeavours or his first meeting with Jawaharlal Nehru, the reader is taken on a walk-through of events, institutions and happenings that are now the staple of history textbooks. A particularly striking example is his narration of the celebratory procession of people in Bombay (now Mumbai) on August 15, 1947, where he was one among the hundreds of thousands rejoicing in their new-found status as citizens of a free country. “It was an inspiring sight to see a famous poet like Josh Malihabadi, a film celebrity like Prithviraj Kapoor with his film star son Raj, a dancer of international fame like Zohra Sehgal, and a front-rank writer like Krishan Chander, singing and dancing in the streets to celebrate this happy occasion….Today, they had come in the midst of the people, as singers of their songs, not to sing about the people, but to sing with the people; not to dance a symbolic representation of life on the stage, but to dance the dance of freedom with the people in the streets.” The collection also offers a peek into his personal life; his own accounts of life as a newly married man and the banter between him and his wife Mujji (Mujtabai Khatoon) are straight out of the myriad Muslim socials that Bollywood was famous for a long time ago. The scenes from his marriage tragically culminate in the death of his wife. Describing the day his wife died in an elegiac memorial, elegant yet heart-breaking, Abbas says: “It looked like her—but it was not her. For that life that was always bubbling with intelligence and compassion was no longer in her. I collapsed near the bed where she lay inert. It was not her—but something resembling her—like the lifeless photograph of a beloved person. When I returned after burying her I walked alone and knew that henceforth I would have to get used to walking alone.” Pathbreaking cinematic efforts Although acclaimed for his association with Raj Kapoor and, of course, for introducing Amitabh Bachchan to the silver screen in Saat Hindustani, Abbas deserves a special chapter in the history of Indian cinema for his breathtaking corpus of work that saw him don the mantles of producer, director and screenwriter at once and also established him as a pioneer whose films broke new ground. He took on challenging issues and translated his thoughts on to the screen, with varying degrees of success. Only a man ahead of his times could make a film like Hamara Ghar (1964), a film about a group of children marooned on an island where the protagonist is a motherless Dalit boy. As Ahmer Nadeem Anwer, who played the lead role of Sonu at the age of 10, says in an essay on the film: “It is this boy who embodies the defiance of those who shall not accept their exclusion from education, work, self-respect—or even recreation and pleasure.” The film, along with several others, is testimony to Abbas’ willingness to take risks and make the cinema that he wanted to make. Collaboration with Raj Kapoor Abbas liked to describe himself as a communicator. “I want to communicate my ideas, my impulses, my ideologies to other people. That is my basic interest in writing, in films and in drama.” It is a moot point which vehicle of communication served his purpose best, but one could not make a better choice than his cinematic collaborations with Raj Kapoor, especially from the early days of the showman’s career, such as his directorial debut, Awara, Shree 420 and Jagte Raho. These films manifest the distilled brilliance of a mind that displays an unparalleled skill in weaving riveting stories for the big screen. His phenomenal grasp of the medium and Raj Kapoor’s showmanship resulted in timeless classics. Abbas himself considered Awara to be the best of his collaborations with Raj Kapoor. It is another story that the two would later go on to make Mera Naam Joker, which Raj Kapoor considered his magnum opus but viewers thought otherwise. The monumental failure of the film devastated him, driving him into debt and depression, and it was Abbas who helped him bounce back by writing the iconic teenage romance called Bobby, which turned out to be Raj Kapoor’s biggest blockbuster. Nehru: A love story It was love at first sight, as Abbas confesses, recollecting the first time he saw Jawaharlal Nehru, at the Aligarh railway station. The essay about the entire episode is a fascinating recollection of an awestruck student meeting his idol in flesh and blood and the resulting conversation, which culminates in Nehru signing his autograph book with the message: “Live dangerously.” Abbas certainly seemed to have taken it to heart, as his life demonstrated. He lived dangerously all his life, always true to himself and never wavering from his convictions, never hesitating to helm a project even at the risk of grave financial loss. He firmly stood up for what he thought was right and did not shy away from opposing what he felt was wrong, irrespective of ideology. His ability to introspect and accept criticism separated him from other giants of the screen or the world of letters of his time. In his tribute, Amitabh Bachchan writes: “Mamu Jaan’s [Abbas] socialism was not just restrained to the books or columns he read, believed and wrote about. He practised it too in the way he lived and conducted his life, and in the way he made his films. I was a newcomer in the illustrious star cast of Saat Hindustani, but his treatment to all was universal. In his eyes we were all equals, and we were treated with the sameness that he followed and believed in.” Ramesh Chakrapani | 19 February 2016 | Frontline India

|

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas