Zaheer Kashmiri: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

“A flamboyant personality, consciously outrageous, bent upon having his say on the subject of his choice, and colourful in his deportment and dress. but all this served as an outer cover (perhaps a disguise) for a heart palpitating on the plight of the oppressed and a soul full of fellowship in sorrow… As an Urdu poet his reputation stands high. Unlike other ‘progressive’ and leftist poets he did not allow his political commitment to make a preacher out of him. The romantic element in his poetry shrugs off the pedantic and the didactic.

“A flamboyant personality, consciously outrageous, bent upon having his say on the subject of his choice, and colourful in his deportment and dress. but all this served as an outer cover (perhaps a disguise) for a heart palpitating on the plight of the oppressed and a soul full of fellowship in sorrow… As an Urdu poet his reputation stands high. Unlike other ‘progressive’ and leftist poets he did not allow his political commitment to make a preacher out of him. The romantic element in his poetry shrugs off the pedantic and the didactic.

… He could be reticent when he was thinking or was uninterested in the subject under discussion. But when he was moved or wanted to make a point his passion rose like a glittering sun emerging out of a grey cloud. Then nothing could stop him. Quoting poets and philosophers he would build his case brick by brick, mortaring every joint, strengthening his argument, and not letting his critics interrupt his foaming flood of words. He spoke often in Punjabi and sometimes in Urdu, but when he wanted to overawe the company he switched to English in which he was unexpectedly fluent and accurate. For a boy who emerged from a lower-middle class background and grew in the lanes of Amritsar in vernacular company and attended a local Muslim college his command of spoken English surprised his friends. He found no difficulty in understanding and digesting obtuse and difficult texts like Hegel and Spengler. I once asked him how he had managed to tackle the Decline of the West. ‘By reading the entire text five times with concentrated attention,’ he replied.<”

One day in 1946 [Zaheer Kashmiri] met me in the Coffee House and asked me casually, “Have you ever watched a film from the 4-anna stalls?”

Let me first describe the hierarchy of seating arrangements in Lahore’s cinemas of those days. The screen end of the hall has pits with hard uncomfortable chairs and each seat cost 4 annas (25 paisas of today). After that was the second class, the largest in the hall, with reasonable chairs with arms, the seats costing one ruppee and two annas each. Above it at the back was the first class, with soft cushioned chairs, and here the fare was two ruppees and four annas. The hall ended here. But above the first class was the balcony where the seats were luxurious and the price three ruppees and six annas. College students with identity cards enjoyed the concession, applicable to all classes except the pits, of paying half the ordinary price of a seat. In other words, they paid 9 annas for the second class, one ruppee and two annas for the balcony. As a student of Government College with a generous pocket allowance and with the half-price concession, I had never contemplated watching a film in the pits.

I replied to Zaheer’s inquiry in the negative, and when he proposed that I should accompany him to a Bhati Gate cinema to watch a film along with the ‘sweating humanity’ (his words) I did not protest.

We met at 5.45 P.M. outside the Gate, he bought two 4-anna tickets, and we entered the hall. Everything inside disgusted me. The benches were of hard wood without a back so that I could not lean back. There were few fans and the place was airless. The audience around me consisted of labourers, street vendors, tonga drivers and the louts of the locality, who talked loudly, often lacing their sentences with obscene but biologically accurate Punjabi abuses, which were so explicit that nothing was left to imagination. Most of them smelt and I felt nauseated. Had Zaheer not been chaperoning me I would have left.

I can’t recall which film it was, but it was an English movie. Whenever a woman appeared on the screen the 4-anna audience squirmed in their seats and passed lewd remarks. When the hero kissed the heroine in a close-up shot there was bedlam around me with catcalls, whistlings and saucy comments like “Oé” and “Haé” and “Mauj Kar gya.” The crowd was exclusively male. Even if I could ignore these problems and concentrate on the film I found that I could not see the figures moving on the screen. Sitting so close to the screen my eyes failed to adjust to the short distance between the viewer and the viewed. What was visible to me was huge men, women horse and wagons (it was probably a Western film) whose abnormal size distorted the picture. Every close-up shot filled the whole screen. There was a disturbing contrast between visual distortion and audio clarity. The picture was enormous and blurred, the dialogue was clear and distinct. I sat through the performance not as a pleasure but as a painful novelty.

When we came out Zaheer insisted that we visit a nearby tea stall, which we did. But it added to my loathing. The shop was filthy, the tables and chairs dirty and rough, and the few customers were brethren of the cinema crowd. After a boy in soiled clothes had slammed two ready-made cups of tea before us with a bang and we had lit our cigarettes, Zaheer immediately embarked upon a lecture on our experience of watching a film in the pits. He talked in English for about ten minutes. I can’t recall at this interval of time his words or the order in which he piled one argument upon another. But I remember the gist of what he said because it affected me deeply.

“I know how uncomfortable you felt there. New surroundings. Strange people. Yes, strange, because they were not the people you meet or talk to. How surprising that you have till today not met these people. They are the unwashed whom you have never met. They are the people for whose freedom the Congress, your Muslim League and my [Communist] Party are struggling. And you have never before met these people whom the whole problem is about. You talk about the independence and the future of the country, but you don’t know the people who live in the country. They smell, but they are the salt of the earth. I am not asking you to mix with them, but at least to be aware of them. I am not asking you to join the Communist Party. I am not a preacher. I demand your sympathy and compassion for these people. They deserve that and as a human being this is the least you can do for them. And I brought you to this apology for a tea house with that purpose in view. I know you don’t like the ambience, the milieu, the quality of the tea, the demeanour of the waiter, the condition of the furniture, the noise and the bustle of the bazaar. But that is where and how people live. Don’t share this condition with them, but be cognizant of it.”

… I often heard my Leftist friends in the Coffee House talking about the poor but their emphasis was political rather than economic and social. Their vocabulary was full of “Marx says,” “the proletariat,” “the economic theory of history,” “exploitation by the rich,” “trade unionism” and such words, but they hardly mentioned the poor, the individual who suffered, the amelioration which was needed, the practical steps which were required. The “socialist revolution” monopolized their debates, not the realities and practical details of raising the level of the poor. They sold Soviet tracts and pamphlets and regurgitated Marx and Lenin. They did not expound the creed of human sympathy and the dogma of natural compassion.

That is why Zaheer’s words struck to my mind and I can reproduce them today, after 61 years. It was a welcome reminder of what I had felt when my consciousness was still an infant.

Khursheed Kamal Aziz (KK Aziz)

Khursheed Kamal Aziz (KK Aziz)

Khursheed Kamal Aziz (11 December 1927, Ballamabad, British India – 15 July 2009, Lahore, Pakistan) better known as K. K. Aziz, was a Pakistani historian, admired for his books written in the English Language. However, he also wrote Urdu prose and was a staunch believer in the importance of the Persian language

The Coffee House of Lahore: A Memoir

The Coffee House of Lahore: A Memoir

K. K. Aziz

Before his death in July 2009, KK Aziz had accomplished one mission that he had set for himself, i.e. to write about the Lahore Coffee House, the glorious nursery of ideas. Luckily, despite his failing health, Aziz finished a draft that was meant to be a shining part of his autobiographical kaleidoscope.

KK Aziz and the Coffee House of Lahore: Chris Moffat

KK Aziz and the Coffee House of Lahore: Chris Moffat

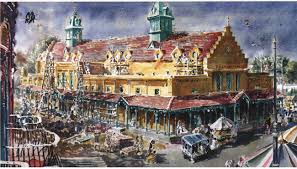

During a recent trip to Lahore, I visited the Sang-e-Meel bookshop on Lower Mall Road in search of K.K. Aziz’s The Coffee House of Lahore. Happily, the store was well stocked with the late historian’s final work, and I spent the afternoon reading the text at a table outside the nearby Tollinton Market.

Book Excerpt: Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

Book Excerpt: Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

the 1920s onwards, perhaps since event earlier, Lahore was the most highly cultured city of north India. From here appeared the largest number of Urdu literary journals, newspapers and books and two of the best English language dailies. The Mayo School of Arts was flourishing. The Young Men Christian Association was active and its premises and hall were used by all communities for literary and social activities.

Muhammad Hasan Latifi: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

Muhammad Hasan Latifi: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

He was one of those remarkable men who arrived in Lahore in 1947 as a part of the flotsam & jetsam of the partition of the Punjab. His acute sufferings began with the ravages of the great migration & ended with his death 12 years later. The story of his life needs to be told in some detail.

Dr. Abdus Salam: The Coffee House of Lahore By K K Aziz

Dr. Abdus Salam: The Coffee House of Lahore By K K Aziz

Among my contemporaries and colleagues in Government College, companions in the Coffee House of Lahore and friends at these places and elsewhere there is only one genius, and that was Abdus Salam. Salam was the son of Chaudhri Muhammad Husain, a schoolteacher of Jhang and Hajirah who belonged to Faizullah Chak near Batala Muhammad Husain was a jat and Hajirah a Kakkezai.

Arab Hotel Lahore: KK Aziz and A Hameed

Arab Hotel Lahore: KK Aziz and A Hameed

No description of the cultural life of Lahore can be complete without mentioning the Arab Hotel. Once the old-fashioned baithaks (sitting rooms of the orient) had gone out f use, the literati wanted a pace where they could meet, eat and talk. For those ‘orientalists’ of the 1920s the Mall was too Westernized, distant and costly. By chance they started patronizing a small, unclean restaurant on Railway Road, opposite the gate of the Islamia College.