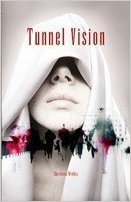

Tunnel Vision

Shandana Minhas

|

Pakistan is much in the world’s thoughts. This touching and spunky story of a young Pakistani woman’s rejection of imposed and stereotyped ‘feminities’ is honest, brutal and timely. The novel is a social form, it is always new, it is cast in the mould of human nature and human society. The subtext of Shandana Minhas’ debut novel, “Tunnel Vision” studies the influences that have led to the peculiar polarization of sexual roles in contemporary Pakistan with style, craft and sensitivity. And yet it is not a story for Pakistan alone, and could, at another level, be set anytime anywhere. The brief biographical note informs us that Minhas has scripted short films and documentaries. There is a decided cinematic sweep to her writer’s vision, and one can almost visualize the camera pan and tilt as it follows the life and times of Ayesha Siddqui, aged 31, of 42D , Street 7, Hussain D’Silva town, North Nazimabad, Karachi. Karachi is very much one of the major protagonists of this witty and exuberant book. Written by a “hardboiled Karachi egg”, it takes the reader through the contradictory landscapes of the metropolis, from the sleek urbanity of the Finance and Trade Centre, through the dark irony of the Gora Qabristan, navigating the perceptive wisdom of street graffiti, truck art and rickshaw poetry. Before Ayesha Siddiqui crashes into the “backside” of a bubble gum pink water tanker, she reads a couplet that sets her aweeping. “Karachi ki aurat kamzor nahin, Karachi ke murd mein zor nahin”, it pronounces. This is the premise from which the storyline proceeds. As Ayesha hovers between life and death in the ICU ward of a city hospital, we follow the defining events of her young life in a series of sharply edited flashbacks. The acid- tongued intelligence of the first person narrative almost never flags. Burdened by intelligence and beauty, the protagonist breaks through the unspoken taboos of the testosterone dominated society into which she is born. Hovering between life and death, she scrutinizes her loved ones with a surgeon’s dispassion and an out-of-body detachment. Abba, her absconding father, an absent presence in the family, is invoked with love, anger, and finally compassion. Ayesha’s mother, the memorable Ammi, is drawn with swift sure strokes. “My mother is one of that special brand of women for whom helplessness is the critical survival material” she begins savagely. The chapter heading is “Maan Ki Dua, Jannat Ki Hawa” – a back-of-rickshaw aphorism. But as memory probes and regurgigates, we envision another woman altogether, an undamaged young beauty who once was Ayesha’s mother. The way in which the parental characters gain in depth and dimension after the soul searching scrutiny of a hurt and traumatized daughter is testimony to the author’s forensic skills. Mamu, Mumani, the impish younger brother Adil, and others in the familial circle are delineated with similar skill and empathy. The sensual maid servant, Nasreen, of the football mammaries, is a piece of quick, perceptive and multidimensional portraiture. The only character to remain disappointingly lifeless, like a daydream or a flat cinema hoarding, is the “hero”, the rich and sensitive bosses son Saad. This is a flaw in the novel. The bright eyed rebellions and assertions of identity come to naught when confronted with the archetypal alpha male, rich, handsome and sensitive to boot. The romance is shown in asexual romantic hyperbole, a complete climbdown from the spirited individuation and heroic struggle that marks Ayesha’s story. As she succumbs to pulp romance, abandoning ambiguity and irony for a predictable fairy-tale denouement, readers are left rubbing their eyes, skeptics among them a bit unsettled by this cop-out. What distinguishes “Tunnel Vision” is its street savvy humour, and its inclusive insider’s vision of what for Indian readers is the fascinating tour through a sibling society so much a mirror of our own. The astute and convincing use of graffiti, rickshaw rhymes, film music lyrics, advertising slogans and back-of-bus wisdom, all in Urdu or vernacular, adds a dimension of on-the-edge artistic tension, of the wide angle drama of a great and discordant city and the individuals who constitute and inhabit it. Whether it is a “Yahaan Pay Pishab Karna Mana Hai” caveat, or an “Allah Ka Karam Hai, Biryani Garam Hai” exhortation, the idiomatic shades and nuances of life in the subcontinent are conveyed without affectation or condescension. Apart from the apt and indicative chapter headings, the language does not lapse from its stylish Sub-continental-spoken-urban-English phrasing. This is a book utterly comfortable in its socio-linguistic skin and situation, comfortable enough to be disquietingly but loyally and lovingly critical. – “Himmat Hai To Pass Kar / Warna Bardasht Kar”. I enjoyed it immensely, enough to forgive its clichéd Toyota Corolla romance. A writer who has the courage and clarity to tell it as it is surely allowed the “Aap Jaisa Koi Meri Zindagi Mein Aye” daydreams of the concluding chapter. I am sure that, like me, other readers too shall look forward to more exposure to Minhas’ unblinking and acerbic novelist’s vision. Namita Gokhale | 8 March 2008 | Sahara Time

|

Paperback: 292 pages

Paperback: 292 pages