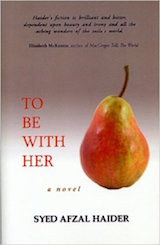

To Be with Her

Syed Afzal Haider

|

Syed Afzal Haider’s debut novel, To Be With Her, traces the journey of a young man perpetually on the move: from India to Pakistan as a young child during the partition; to Stillwater, Oklahoma, for college; then to Chicago for work; and, finally, home again, where Ramzan Pervez Malik, or Rama, must decide between old love and new. “You can leave places,” young Rama thinks as he gazes at the night sky from the boat that takes him away from Pakistan for the first time, “but your losses travel with you” (Haider 81). Rama’s Bildungsroman unfolds in, what Bruce Robbins calls, “actually existing cosmopolitanism […] a reality of (re) attachment, multiple attachment, or attachment at a distance”(3). Rama’s cosmopolitanism allows him to see America as both a land of “freedom” and entrapment, since “only in America do they have factories that make products that they use to pack other products”(Haider 112). “Packed” in much the same way as other American “products,” Rama can no longer return home the same young man that he was when he left. His relationship with his homeland, his Pakistani fiancée, and his family is uncertain, and he must decide if “home is where the heart is buried,” (247) or if, as he tells his sister, “it is not the end of the world. In fact, it is the birth of a new world for all of us” (245). To Be With Her explores the trajectory of places lost and found as Rama comes of age both at home and abroad. Some of his “losses” are those typical of the Bildungsroman—innocence, naiveté, and ideals—while others are the product of his exposure to “real” American society, which is not like the movies he watches, but instead a place where “prejudice [is] based on the color of one’s skin”(103 emphases in original). Haider filters Rama’s growing disillusionment through Rama’s encyclopedic knowledge of American cinema, enacting the argument that “we are connected to all sorts of places, causally if not always consciously, including many that […] we have perhaps only seen on television— including the place where television itself was manufactured”(Robbins 3). Even before Rama travels away from his native India and Pakistan, he journeys into the world via the silver screens of the Majestic Cinema near his home. Young Rama, who sees “life as a movie,” fashions himself as “a good guy, a main character, a matinee idol, leading man material” (Haider 9). Rama plans to study abroad in order to seek his fortune as a college-educated engineer while maintaining a relationship with his girlfriend, medical student Leila. Though Leila tries to break things off—“this movie is over,” she tells him (65)—and correctly predicts that his journey to America will divide them, Rama convinces her to stay with him. Leaving for America, Rama tells his family that he wishes to wed Leila and they happily accept his choice. “I don’t mind living in exile,” he tells his college crush, Lisa, “but I would like to die at home”(125). Multiply attached, Rama still views his homeland as a place he must inevitably return to. Haider frames the narrative of Rama’s “journey,” “education,” and “home,” by referencing Gone with the Wind at the beginning and end of the novel. This reference evokes the scene of Scarlett O’Hara clutching the dirt of her beloved “Tara” in her fist, swearing that she will re-make her life on the scorched earth left to her by the Yankee soldiers. The (home)land represented by this earth suggests that a single, essentialist identity is possible within the narrative of the film (and the American South). But this simple explanation is quickly belied by Rama’s actual experience of American racism. The adult Rama looks back at the injustice behind the American culture industry: “The year I was born, 1939, Gone with the Wind (220 min., Technicolor) won the Oscar…but more importantly, Hattie McDaniel was the first black actress to win an Academy Award…Hattie McDaniel and her escort were seated at a table in the back, near the kitchen”(9). The charmed life of the big screen is undercut by the realities of American work, which he finds tedious, and the “available” American women (goris), who he finds confusing and unlike Leila. At first, Rama can fill pages with his devotion to the symbol of his home(land), Leila, who waits patiently in Pakistan and sends him letters on pink scented stationary. But the longer he spends in America, the less he finds to say to her, or to anyone. He begins to “learn all the great American phrases” such as “no kidding” or “you know,” and soon he is “shrugging my shoulders like ‘the natives’ without even knowing it” (113). On a date with the beautiful Alice in Chicago, Rama pretends to be his lady-killer roommate, Latif. He longs to “hold her in my arms and kiss her like Burt kissed Deborah in From Here to Eternity”(122). But by the end of the date, “I didn’t even tell her my name”(122). Through silencing Rama, Haider demonstrates the impossibility of simply slipping unscathed into the “Roman” lifestyle of America. It isn’t until he meets Sabina, a fellow “outsider” who holds multiple and conflicting identities—Jewish but often passing as “white” and a jealous espouser of “free love”—that Rama is able to (re)attach in America. Sabina is the “unknown that my heart craved in this foreign country”(152). Though she loves Rama as well, Sabine pushes him outside of his comfort zone and forces him to acknowledge his connection to the world around him, stating that “war is a global issue […] not a local one” (177). Rama visualizes his attraction to Sabina not in American movie terms, but in the Hindu tale of Rama, his namesake, and Rama’s wife Sita. This cosmopolitan assemblage of multiple cultures, faiths, and continents “is a scene from a movie I always wanted to see but hadn’t yet been made” (141). Re-writing the script of the love stories he has spent his life watching, Rama now becomes the “protagonist” that he wants to be. It is only with Sabina that Rama can begin to puzzle out who he is and speak freely about what he wants. He is now the actor, not the acted-upon: “for once I’m at peace. There are no background noises. I’m not asking any questions”(145). At the end of the novel, when Rama is on a flight back to America—and Sabina—he dreams of work-shopping his own autobiography. His book, unlike Gone with the Wind, is said to have “too many unexplained moments in it”(248). Rama knows that he shouldn’t take this as a compliment, but he does, recognizing that “if I observe a moment of silence for every place I have left, for everyone who is gone and everyone absent […] I’ll never speak again”(248 emphases in original). The act of speaking, of telling a story that doesn’t begin or end like a movie, is his triumph. Haider allows Rama to accept his losses without categorizing or finalizing them, to exist both at home and abroad as an actual(ized) cosmopolitan thinker and man. Hillary Stringer | Vol. 3, No. 3 (2011) | Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies

|

Paperback: 240 pages

Paperback: 240 pages Syed Afzal Haider

Syed Afzal Haider