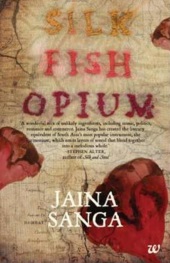

Silk Fish Opium

Jaina Sanga

|

|

Silk Fish Opium is the first novel by Jaina Sanga, a prolific author best known for her short stories and critical work on Salman Rushdie. The novel moves between the romantic and the political, a brisk leaping between genres. Extraordinarily gripping, the novel succeeds in reaching out to the emotional complexities of its characters, becoming a chronicle of the fallout of the partition on the Hindu-Muslim communities residing in the country. Readers who can hang on to the claustrophobic initial chapter of the mock cremation of Rohini, the female protagonist, performed by her Hindu family to completely obliterate her from their lives, are rewarded with a narrative that keeps pace with the emotional involvement of the two protagonists. As the emotional stakes rise, the story becomes compulsively engrossing; warm, honest details of the relationship and the family business of silk and their inheritance from their great grandfather’s opium trade are interspersed with scattered comments on the workings of the Muslim League, of Jinnah’s call for a separate nation, and the resentment against the protracted stay of the British in India. An evocative, engaging novel about a Hindu-Muslim alliance, the story is set during the time of pre-Independence, Independence and Partition. The novel moves from India to America and then to Pakistan, a remarkable blend of music, politics, romance and commerce that involves trade in opium, silk and fish. It is a period of extreme animosity. Just when India is poised for Independence, young Rohini, the daughter of a rich silk merchant falls in love with a music teacher. As the two-nation theory takes shape and the Hindu Muslim conflagration becomes inevitable, Rohini and Hanif draw closer to the decision of getting married, a step that would take them into a sad confrontation with tradition and modernity, with a deep-seated parochialism and an urge to step beyond the constraints of one’s religion or caste. They begin to meet in cinema halls, at railway stations, always worried that these clandestine meetings might be discovered by her parents: “Six o’clock in the evening; she should be on the train home by now. She would say she had to stay late for tutorials. She glanced at him, then quickened her steps and moved ahead. Did it look like they were walking together?” In a matter of days letters from Hanif are discovered in her cupboard and the secret is out. Finally, giving up her family’s fortunes and a marriage with a wealthy diamond merchant from South Africa, she elopes with Hanif. The only time Rohini feels safe and loved and secure is when she is with him. She longs to see him, shed all her Hindu “baggage” and be with him, and in these few moments try to forget all the social pressures. But even then, going home every day was in a state of fear and nervousness, of being “found out”, so she could never really throw caution to the winds and live fully in that moment. But she is grateful that she has him in her otherwise troubled present. The only constant about life is that it is a constant challenge. The overarching theme in our lives is our expectations of ourselves, others’ expectations of us, boundaries established by our conscience, limitations of relationships, and reconciliation of those limitations within each of us and finally, how will we ultimately come to terms with what makes us truly happy with what makes us socially accepted. What is this entity called Conscience; we were not born with it, we were conditioned by our environment to acquire it, an unwritten set of rules of right and wrong as established by our society, and collared by our religious tenets. When Rohini offends this so-called rule keeper called conscience, she suffers from pangs of regret, guilt, remorse and self-recrimination. She cannot now withdraw into the boundaries established by society, and as an individual, her future happiness depends on her rebellion. Beneath the outward calmness of a cerebral, rational conscious mind, is the sea of uncontrolled, repressed, wild emotion and palpitating passion she has for Hanif which is constantly pushing both of them to leap over those limits of conscience and racial constraints, to declare themselves as the masters of their destiny rather than the supplicants of their religious affiliations. This tussle goes on in each one of us; for some, the conscience will triumph ultimately; others will always be living and struggling with this duality. Shall I be happy when the world thinks I should be happy, or shall I define my own meaning of this word? When is the right time to define my terms of individual happiness and is it possible to do this at any time, or one must reconcile this innate desire with the worldly responsibilities which one cannot arbitrarily relinquish? This is the existential choice before both Hanif and Rohini. It makes Rohini think about herself, struggling to find someone to blame outside of herself, looking more inward, and finally reconciling with the reality of existence and the need to take up some personal responsibility in the face of a very hostile world. It is as if she was saying: “I want to live my life, not just work my way through it. There’s mystery out there, romance. I want to feel taken care of.” Shelley Walia | 2 March 2013 | The Hindu

|

Jaina Sanga

Jaina Sanga