Revisiting Ahmed Ali: Twilight in Delhi (1940)

Amardeep Singh

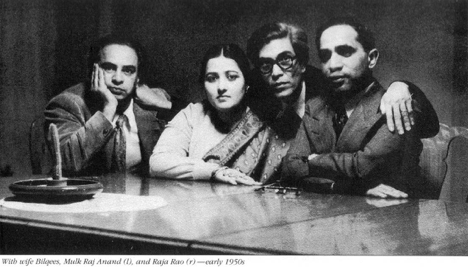

Ahmed Ali with his wife Bilqees, Mulk Raj Anand, and Raja Rao (early 1950s)

Ahmed Ali’s career is one of the best ones I know to illustrate the connections between the style and ideology of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and more experimental and lyrical modes of mid-20th century writing in India and Pakistan. Ali is best known for his English-language novel, Twilight in Delhi (first published in London by Hogarth Press in 1940), but he wrote several other novels in English, as well as a number of short stories and plays in Urdu in the 1930s. He was one of the “Angare Four” — one of the four authors who contributed short stories to a collection called Angare in 1932, which was furiously condemned by the Indian Muslim community and banned by the British government for material deemed offensive to Muslims in particular. He was also one of the co-founders of the All-India Progressive Writers’ Association AIPWA, in 1935-6. Around 1940, however, he left the movement following disagreements with its leader, his friend Sajjad Zaheer. Like many of the other major Indian Muslim intellectuals of his era, Ali had spent some time in Aligarh at the Aligarh Muslim Anglo-Oriental College (today known as Aligarh Muslim University), an English-medium college that was also known as a reformist hub. (E.M. Forster’s friend Syed Ross Masood had a connection to Aligarh.)

Thanks to the Annual of Urdu Studies, we have a lot of biographical material about Ali freely available online. Start with this annotated CV. Then see Carlo Coppola’s survey of literary Ali’s career here. Ali went into diplomatic service right around the time of independence, and was assigned to China. After Partition he elected to make Karachi his home, and later continued to work as a diplomat and a businessman there. In the 1960s, he published a second work of literary fiction in English, Ocean of Night. In the 1980s, he published a diplomatic satire called Of Rats and Diplomats, as well as a self-translated volume of his earlier Urdu short stories from the 1930s and 40s, The Prison-House. I’ve looked at all three novels, but the only one I can recommend is Twilight in Delhi (the short stories are also recommended).

In the volume that started it all, Angare, Ali has two short stories, Badal Nahi Aati (The Clouds Don’t Come) and Mahavaton ki ek raat (One night in the winter rains). “The Clouds Don’t Come” was translated by Tahira Naqvi for Michigan State’s Journal of South Asian Literature (JSAL). As far as I know, “Mahavaton ke ek raat” has never been translated into English [I’m actually working on doing one, albeit with help.] Indeed, as I understand it, despite its importance as a starting point for the Progressive Writers’ Movement, Angare as a whole has never been translated into English; at best we have a few selections here and there in journals like JSAL. I also can’t find any evidence that it’s ever been republished in India since it was banned by the British in 1933; the only re-publication I know of is an Urdu edition published in England around 1988. (That is, needless to say, the version I myself am looking at; the original, banned Angare is nowhere to be found.)

* * *

Before getting into Twilight in Delhi, it seems appropriate to briefly quote from the experimental, stream-of-consciousness text of “The Clouds Don’t Come,” which is important as a starting point in Ali’s career. It also has some important points of intersection with the subsequent novel. (Another story that shows some clear overlap is Ali’s Urdu story “Hamari Gali” [Our Lane], which uses the same paratactical technique — following the random encounters and characters who show up in a particular neighborhood of Delhi — and which even has some actual characters who Ali also figures in Twilight.)

“The Clouds Don’t Come” is not the most scandalous story in Angare. By far, the story that has been singled out most frequently is Sajjad Zaheer’s “Sleep Doesn’t Come” (Nind Nahi Aati), which features a devout elderly man who is preoccupied mostly with religion, at the expense of his young wife. While trying to do night-time prayers, he falls asleep, and begins to have erotically charged dreams related to a vision of Paradise. Zaheer’s story is a flagrant provocation, which would likely be as offensive today to pious Muslims as it was when it was first published in 1932 (luckily, most people have long since forgotten about this story).

Ali’s “The Clouds Don’t Come” shares the anger about religious conservatism, but uses a more carefully leveraged attack. The narrator is a woman who feels oppressed by the heat, but also by her confinement indoors in the middle of the Delhi summer. The story is essentially her first person, stream-of-consciousness rant, with the most powerful condemnation of traditional gender relations coming in the following section:

Why don’t the clouds come? And life is despair. Despair, hair, long and black, such a hardship. Why can’t we cut it like men do? It’ll make one feel so light. Father, God rest his soul, had a crew-cut. And once, when it was as hot as it is now, he had his hair cut even shorter, and then Sabira and I washed it thoroughly. I wish we too had short hair. Scalp’s burning; it’s scorched. And to make matters worse, we can’t cut our hair. The family has enormous honor, and if we cut our hair, the family’s honor will also be demolished. If I were a boy, I’d shear it off with a dull blade, chop it from the roots. And what fear of honor being damaged when there’s none to begin with? […] Whether you want to, or not, your blasted husband will take you forcibly by the hand… come here, my love, my dearest, such fire in your coquetry. How cool the room! Light of my heart, come to me. Get away! Always lusting night or day! Oh! Kill me, strike me with a dagger… twisted my poor hand, broke it. Where are you running off to? Lie down next to me! Here’s a taste of the dagger. Those hands, running over breasts again, crushed, crushed, the wretch squeezed so hard, I couldn’t move, may he die young. Even prostitutes aren’t treated like this. The moment I rested my weakened body, he vent his frustration with the torrid heat on me. Why do you lie there like a corpse? Make an effort.

[…] And we can’t stop burning, we shed a thousand tears! The terrible fire in which perpetually burn will not go out; death won’t come. Hindus are better off than we are, they’re free. And Christians—they’re so fortunate. They’ll do what they want, dance, look at pictures, have short hair, says the narrator. How unfortunate that we were born in a Muslim household, may such a religion perish. Religion [Urdu: Mazhab], religion, religion is the soul’s solace, the security of men. What good is it to a woman!

The key provocation is of course at the end of the passage above (“What good is [religion] to a woman”), though the anger simmers throughout the speaker’s interior monologue. One also notes the explicit account of what amounts to marital rape.

The recurring motif of the story, of the speaker’s desire for clouds to come in order to change the weather, is a clear (one might even say, obvious) symbol for social change. The coming of the clouds will change the speaker’s circumstances, and give her some control over her life. Under the direct glare of the sun, she’s rendered paralyzed and inert, unable to alleviate her misery in the least.

* * *

The figure of twilight, so central to the thematics of Twilight in Delhi, actually is actually somewhat similar to the figure of the cloud in “The Clouds Don’t Come.” As with the earlier short story, Ali is particularly interested in showing a set of characters who are essentially stranded in their particular present, waiting for a change (in this case, the advent of “night”) that promises change.

Unlike Ali’s more optimistic progressive peers, Twilight in Delhi may be seen as a work of modernist pessimism, looking at characters in a historical setting, who are themselves looking forward blindly. The book is an elegy for Delhi life in the 1910s, just before the British recreation of the city, the massive building project designed by Edwin Lutyens that eventually led to the advent of New Delhi.

Within the novel itself, Ali’s characters are split, with the elderly Mir Mihal largely glancing nostalgically to the glory days of his youth as well as the fallen Indo-Islamic heritage of the subcontinent, seen in ruins after the failure of the 1857 Rebellion/Mutiny (a beggar appears in the novel who is nicknamed “Bahadur Shah”; he’s known mainly for reciting the “last Mughal’s” famous verses about exile and loss). Mir Nihal’s son Asghar, by contrast, aims in fits and starts to find a way to a possible future, only to be stymied at every turn by a conservative social order. The novel is divided in its attention between father and son, ultimately committing to father over son, past over future, aware that its retrospective gaze can only be a tragic one.

Twilight in Delhi is also a backwards-looking gesture from a bio-critical perspective – as it represents the author’s definitive public break with the Progressive Writers Movement he had helped found six years earlier. With its moody interiority, Twilight in Delhi also marks Ali’s stylistic break with social activist fiction. The novel’s characters are nominally anti-colonial, but have no self-consciousness about their own role in subjugating others, especially women, and Mir Nihal is reduced effectively to nurturing a diminishing stock of pet pigeons on the roof at the expense of the human relationships in his life. Despite the overlapping and overdetermined retrospective qualities of the novel, Twilight in Delhi cannot help but also be in some sense a proleptic gesture: a Twilight that looks back on the day that is ending (the British Raj, the Indo-Islamic legacy in Indian society), which cannot help but also look forward to the oncoming embrace of a spirit of newness entering the world at night.

With Asghar, the desire to marry for love rather than through a conventional family arrangement is at times directly linked to his forward-thinking and ‘modern’ identity. Asghar is in love with Bilqeece, the sister of his best friend Bundoo, of whom his father disapproves on account of her slightly lower birth. Much of the early plot of the novel (though it should be noted that this is a novel where style and mood are much more important than plot), revolves around this crisis. The link between love marriage and progressivism can be seen in passages like the following:

‘I won’t marry any other girl,’ Asghar said peremptorily. ‘I will marry her or no one else. You know that none of my wishes have been fulfilled. I wanted to go to Aligarh to study further; but father put his foot down. He wouldn’t hear the name of Aligarh. It is after all a Muslim institution, but he says that it is all the evil-doing of the Farangis who want to make Christians and Atheists of all of us. But that is finished now. I have given in to him. But in this matter I won’t listen…’

Aligarh MAOC was of course the college that Ahmed Ali himself attended, at the time the center of progressive thinking in the Indo-Islamic context. Asghar has lost the battle with his father to go to Aligarh, but seems determined to win with regards to his marriage interest.

Asghar does eventually win when his mother goes behind his father’s back, and arranges for the marriage to Bilqees to go ahead; his father eventually gives his assent. But Asghar quickly comes to realize that a progressive motive for marriage, driven by romantic idealization rather than family obligation, is not really sustainable when it is purely one-sided – in this case, in Asghar’s own head. His idealization of Bilqees, he realizes after the marriage occurs, is not reciprocated, as she has a much more traditional idea of her role as a wife than he does of her.

*

In the background of Ali’s novel are a series of major historical events in India in the 1910s, beginning with the Coronation and Durbar of King George V, which was celebrated (one might also say, enforced) in Delhi on a vast scale, providing massive spectacle intended to impress upon its subjects the immense power of the British Empire. (Film footage from the Coronation and Durbar can be seen on the web here: http://www.britishpathe.com/record.php?id=51998 ) Later events narrated over the course of the 1910s include the advent of World War I, the terrible Influenza epidemic of 1918, and the rise in anti-colonial agitations with Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement in 1919.

These public historical events afford Ali spaces to step back from the direct narration of the story to give an idea of Delhi’s public spaces:

People all around were talking:

‘Is that the King on the horse?’ said one.

‘Don’t be mad,’ another ridiculed him. ‘he is a mere soldier or officer. Kings wear fine and flowering robes.’

‘That’s all you know,’ a third butted in. ‘The English wear only those uniforms. Understand?’

Many passed caustic and humorous remarks on the dress and faces of the native chiefs, laughing at their retinues, calling them tin soldiers or made of straw. The children were excited by the sight, and gloated over liveries and uniforms and so many white faces as they had never seen before. They shouted and asked questions from people who either did not know the right answers or were too busy themselves watching the fun… (108)

The idea of public space introduced in passages like this may seem extrinsic to the novel’s plot, but as I read it it’s these passages that give the novel its ‘modernity’. In passages like the one above we see voices of ordinary, anonymous citizens (here seen as bewildered and comical), but elsewhere they are posited as a ‘modern’ counterpoint to the conservative posture of Mir Nihal and his family.

Ali often figures flocks of domesticated pigeons as well as kite-fighting as proxies for the public space of Delhi. These are both activities engaged in from the roofs of the old houses like the one the Nihal family inhabits. Both the pigeon-keeping and kite-fighting have elements of chance and unpredictability to them – elements beyond Mir Nihal’s or Asghar’s control – and that element of chance seems like an important corrective to an extended family and enclosed society that often seems stiflingly limited.

One passage that poses the pigeons in particular as a proxy for a Delhi public comes after Asghar’s relationship with Bilqeece has begun to sour, and foreshadows (prolepsis!) her death and the disappointment of Asghar’s dreams of romantic fulfillment (or in a more modern frame, a companionate marriage):

One evening she was sitting alone. It was one of those rare evenings in October when summer is departing and there is a feeling of autumn in the air. The sun was setting and had coloured the sky with passionate colours; and a gentle sadness was in the atmosphere like the memory of bygone love and happy dreams. The rooks cawed and wheeled and circled over towering trees, settled down on the branches, then rose again cawing loudly in a chorus. The pigeons flew in flocks, tame pigeons flew in flocks, tame pigeons of the pigeon-fliers, and wild pigeons going to their nests and resting-places for the night. A beggar was whining in fron of a door somewhere in the by-lane, blessing a newly married couple:

‘May Allah keep the bridegroom and bride happy and well…’ (148)

Unfortunately, given what happens on subsequent pages, this is negative foreshadowing: neither bridge nor bridegroom are going to come out of the story at all happy — or well.

*

The central change in Delhi that Ali’s novel doesn’t really engage for obvious historical reasons is the construction of a vast new city adjacent to the existing city of Delhi. This new city would house all of the major official buildings related to the administration of the British empire, and would be spacious, vast and regal – effectively designed for automobiles rather than horses and pedestrians – in sharp contrast to the cramped streets and generally unimpressive structures of the older city.

Here is the one passage where the plan for New Delhi is named and described – the plan was only in its early stages in the 1910s, and most of the work on New Delhi was performed in the 1920s.

Outside the city, far beyond the Delhi and Turkoman Gates, and opposite the Kotla of Feroz Shah, the Old fort, a new Delhi was going to be built. The seventh Delhi had fallen along with its builder, Shah Jahan. Now the eight was under construction, and the people predicted that the fall of its builders would follow soon. Its foundations had at least been laid. From that eventful year, 1911, which marked in a way, the height of British splendor in India, its downfall began. [….]

Besides a new Delhi would mean new people, new ways, and a new world altogether. That may be nothing strange for the newcomers: for the old residents it would mean an intrusion. As it is, strange people had started coming into the city, people from other provinces of India, especially the Punjab. They brought with them new customs and new ways. The old culture, which had been preserved within the walls of the ancient town, was in danger of annihilation. Her language, on which Delhi had prided herself, would become adulterated and impure, and would lose its beauty and uniqueness of idiom. She would become the city of the dead, inhabited by people who would have no love for her nor any associations with her history and ancient splendor. But who would cry against the ravages of time which has destroyed Nineveh and Babylon, Carthage as well as Rome? (144)

The central paradox of Twilight in Delhi is its commitment to posing Delhi as on the verge of a historical abyss — a city on the edge of ruin — even as its author is situated some thirty years later, well into what should by all accounts be seen as the foreshadowed ‘night’. In that sense the novel is anti-progressive; the prospect of new immigrants is figured as a cause of further decline, rather than rejuvenation. And the prospect of an anti-colonial politics or social reform (such as one might see with Aligarh MAOC, or Gandhianism) is seen as a dead end for Ali’s characters.

That said, the novel still feels like a work of modernism for formal reasons. Ali’s novel is clearly and by even a relatively conventional critical standard formally modernist, specifically its “paratactical” urban method, which resembles the urban rambling of Ulysses at some moments, and the crystallization of multiple perspective around a singular event one sees in Mrs. Dalloway (Ali’s account of the King’s Coronation and Darbar may be seen as an echo of the King passing by in his car in Woolf’s novel; it also calls up the “Wandering Rocks” episode of Ulysses).

In its anti-progressive thematics, Twilight in Delhi is perhaps in good company with the many British and American works of modernism that expressed ambivalence about the present moment, insofar as “modernity” seems to require the decline of a viable high culture. (One can see a definite change in direction along these lines from Ali’s first short stories. “The Clouds Don’t Come” is driven by animus against tradition and the conservative implications of Islamic culture; though religious tradition is far from embraced here, that animus has largely dropped out by Twilight in Delhi.) The lamenting of decline was also T.S. Eliot’s posture, of course, and to an extent Yeats’ as well. As with those poets’ work, Ali’s novel seems to in some ways be symptomatically modernist despite itself, as the last line in the passage above suggests: “But who could cry against the ravages of time, which has destroyed Nineveh and Babylon, Carthage as well as Rome?” Forward-looking time seems to point inexorably to “annihilation,” but the narrator is nonetheless quite clear that forwards is the only direction in which we can go.

(Amardeep Singh teaches at Lehigh University in eastern Pennsylvania. He works on British colonialism, modernism, postcolonial/global literature, and the digital humanities.)