Phoenix Fled

Attia Hosain

Paperback: 224 pages

|

In 1953, Attia Hosain published her first book ‘Phoenix Fled’, a collection of short stories, with Chatto and Windus. In 1988, ‘Phoenix Fled’ was re-issued by Virago with an introduction by writer Anita Desai. The introduction and the first story, “The First Party”, have been digitised. “The First Party” explores the conflicts between tradition and westernisation as a young Indian bride has to come to terms with her husband’s western habits of “drinking” and “smoking”. Hosain’s stories are rich portraits of her own experience of growing in a feudal or taluqdari household. As stated by Lakshmi Holmström in her essay “Attia Hosain: her life and work”, which was published in the Indian Review of Books: “It is immediately apparent that the sub-text of these stories is the tension between the author’s persona as taluqdari daughter, and her persona as a socialist”. The stories often explore the lives of women who come from different social backgrounds. “Listen to me, child. You will be a woman soon and must behave well and with modesty. The Kazi will ask you three times whether you will marry Kalloo Mian. Now don’t you be shameless, like these modern educated girls, and shout gleefully ‘Yes.’ Be modest and cry softly and say ‘Hoon'” A marriage is arranged between a little servant girl and a middle-aged cook with an opium habit; an idealistic political worker faces disillusionment; a servant returns to a wife he scarcely knows; a conventional bride has her first encounter with her husband’s “emancipated” friends: telling of the lives of servants and children, of conflict between the old traditions and the new, modern civilisation, and exploring the human repercussions of the Muslim/Hindu divide, these twelve short stories present a moving and vivid picture of life in India. To each episode Attia Hosain brings a superb imaginative understanding and sense of poignancy of the smallest of human dramas.

Attia Hosain on Phoenix Fled (1991)ATTIA HOSAIN (AH): About the books. I always wanted to write, I wrote short stories when I was at the [Isobella Thoburn College, Lucknow] college and one was published in their collection, I still remember. Why I remember, it’s amusing, is because all of us had to write these stories and then they were read out in class. And at one point, one of my very close friends, she had written a story and I giggled at one point which was sort of romantic and sentimental. And the teacher who was an American with a very severe face, looked at me and said “And why are you laughing?” I said well, it was a bit sentimental, wasn’t it? She said if there had been more sentiment in your story, it would have improved it. I always wanted to [write] and they would go round and round in my head and sometimes I would put it down and sometime I wouldn’t. And they were published, some of them, in papers and magazines in India [like The Statesman or The Pioneer], in those early years. QUESTION: It was like 1930, 1940? AH: In the late, late 30s and early 40s but – Q: Were you writing in the context of Sajjad Zaheer [of the Progressive Writer’s Movement] and all of that, were you reading them? AH: No. [I was] totally influenced by the West, I think, in a way but completely about my own cultural backgrounds and patterns of thought. I did not read much about Urdu literature except when I had to, because it was easier and quicker I mean when from the age of three you were brought up in an English school. True, you are taught all the rest at home but there you are and you are having to write down when you get to your college. How many books you have read when and what and you are racing through them because I could read fast, thank goodness, and I had a good memory then. I was very fond of reading as I told you. So, no it had nothing to do with them. They didn’t influence me at all in my writing. They merely influenced me in my thinking politically, in no other way I don’t think. I used to write as I say, these stories and then I came here and when I made this absurd decision that I would sit up in an attic and do something with my life now. At that time I hadn’t yet begun at the BBC because some of the people who were originally in Lucknow and had gone to Pakistan and then come here to the BBC at that time thought I was one of those [snobs] ‘Oh there she came from that big house and you know it is a kind of hobby she wants or something.’ I didn’t. I wanted work, I wanted some one to realize that this was not a person who was just faking. So I’d sit up there in that little room of mine which I had got inexpensively, in of those terrible, modern blocks where you don’t feel at home at any time. A friend of mine had helped me as I did not know London then except as a literary place. I sat there and wrote. I had written. I was a kind of a journalist in India after I got married. I wrote for somebody here, for a little magazine that used to come out in those years, called Liliput which is a little magazine, which had all kinds of stories and all sorts of things. Rather a cult magazine, as it became. I don’t know why I wrote that story [‘After the Storm’], I think, to earn a little money because it was published in a magazine here. A friend of mine said that is a good story why don’t you sit and write. I said how can I? Well I sat and it was days of rationing. And this kind friend [William Rawlinson, whose own family had been refugees from Nazi-occupied Lithuania, finding shelter first in Bombay before going to England and knew Ali Bahadur when he was Supply Commissioner, Govt of India in the Second World War] would bring me my bread and milk or whatever and I’d be sitting there writing this, and walking to the BBC and come back walking along the road and stories would keep coming in my head. I think I was unhappy, lonely, felt terribly home sick. My children, poor little things, had been put in boarding and it was altogether misery, I think, that made me write. And I wrote those stories and that is it. And this very friend then said and I have never, never stopped, being grateful. Whenever I ring him and his wife, I always say that you remain special because of what was done. He took it. Had it all typed properly and everything, all this collection, there were more stories than came out in Phoenix Fled . He said why don’t you take it to your friend Lord Dunsany. Now Lord Dunsany was the old writer. Old gentleman, eccentric wonderful man. I showed them to him. I used to be very apprehensive about showing anything I wrote. He said now these are good enough to send to an agent. He sent them to his agent but his agent didn’t think that they could be published. They came back to me and this other friend just took them from me. One day I got a call from somebody who became later a great friend of mine, and agent called Joyce Wiener who was then one of the top agents here and she said I want to tell you that Chatto wants to publish your whole book. The Hogarth Press wondered whether they should do it or should Chatto do it? This was Phoenix Fled and I thought I’d die. I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t have dreamt of it. So they chose from the collection. Q: Were those stories trying to deal with partition in any way? AH: They were more – Well the first one, in a way you can see that it is the partition. There is one about a little girl after the storm. It could be that or it could be a riot. But it is about violence. Not all of them were about that [partition] but these two definitely have that hint of it. Attia Hosain: A Writer’s Partition

|

Attia Hosain

Attia Hosain “Storm” by Attia Hosain

“Storm” by Attia Hosain Distant Traveller: New & Selected Fiction

Distant Traveller: New & Selected Fiction Sunlight on a Broken Column

Sunlight on a Broken Column

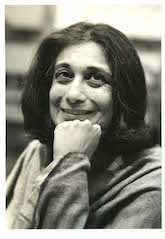

Hosain 1913-1998

Hosain 1913-1998