Muhammad Hasan Latifi: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

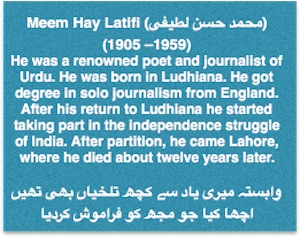

He was one of those remarkable men who arrived in Lahore in 1947 as a part of the flotsam & jetsam of the partition of the Punjab. His acute sufferings began with the ravages of the great migration & ended with his death 12 years later. The story of his life needs to be told in some detail.

He was one of those remarkable men who arrived in Lahore in 1947 as a part of the flotsam & jetsam of the partition of the Punjab. His acute sufferings began with the ravages of the great migration & ended with his death 12 years later. The story of his life needs to be told in some detail.

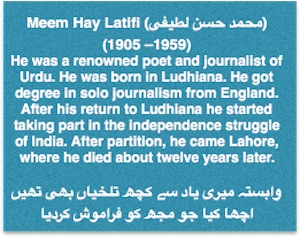

He was born in 1905 in a rich family of Ludhiana. His father was a wealthy military contractor who had established his business in 1866 & then expanded it to several cantonments in northern India.

Latifi graduated from the University of the Punjab, took his M.A. degree in English from Aligarh & received a diploma in journalism from Oxford or London (sources differ on this point). In England an English girl, Norah, fell in love with him & wanted to marry him, but he refused because of his dislike of British imperialism. On the same ground he declined the offer of a well paid job in the department of information of the Government of India. This was in 1931. He settled down in Ludhiana & embarked on a most unusual literary career.

He moved from his ancestral mansion in Kucha Mian Shah Muhammad & built his own bungalow on Kamran Road, & gave it the French name of “Chateau”. At the back of his house he established a small printing press. He had been an ardent book buyer since his Aligarh days, & had bought 2,000 books while in England. He went on adding to it & thus had a well-equipped collection at his disposal.

On 15 April 1932 he started what he termed his “solo journalism” by issuing a bilingual weekly in Urdu & English called Mutala’a, which was entirely written by himself & contained both prose & poetry. It lasted till 1947. He had a good command of English, Urdu, Persian, Arabic, French, German & Italian, but his native tongue was Punjabi. He wrote in Urdu, English & French, translated essays & stories from French, German & Italian. He knew & corresponded with a large number of his contemporary men of letters including Iqbal whom he had first met in London in 1931. He was a prolific poet in Urdu & left a corpus of several thousand verses. In poetry he was specially close to N.M. Rashed & Akhtar Shirani. His influence on Rashed contributed a strong element of classicism to the work of the father of modern Urdu verse. He translated some French lyrics for Akhtar Shirani which added to the thought & vocabulary of the founder of Urdu romantic poetry. According to some critics, Latifi is the only major poet of the period between Iqbal & the modern poetry of the 1940s.

The Punjabi classic Hir Ranjha was a major interest of his life. He spent 5 years in preparing a book called Hir Ranjha, for which he visited Jhang several times & did a lot of research. It was planned in several volumes. The first volume, entitled Glimpses of Jhang History, ran to 500 pages & contained several diagrams, maps & illustrations. It was scheduled for publication from Jhang in June 1951, but for some unknown reason nothing happened. A few passages from it had appeared in a Lahore daily The Civil & Military Gazette.

He migrated to Lahore in September 1947, & the agony of his life started. Economically he was now a penniless wretch. He did not put in any claim for compensation or allotment of evacuee property for what he had left behind: his ancestral mansion, his own bungalow, his printing press, & some more houses & shops of which he had been the sole inheritor, being the only son of his father. He had four sisters, & before 1947 he had, in the teeth of opposition from his relatives & friends, given them their due share from his property in accordance with Islamic law. He now believed that getting compensation for his losses vitiated the spirit of hijrat (migration in the cause of Islam). A man from Ludhiana who had benefitted from Latifi’s generous philanthropy in his good days, arranged a modest house in Krishan Nagar where he lived for a few years before leaving for Rawalpindi.

Intellectually, after his rewarding & rich literary career in Ludhiana & his other accomplishments, he felt deserted. His real life, he realized, had come to an end & only a corroding disillusionment lay ahead. Lahore’s culture life had been ripped apart by the Partition. People were living in a limbo. In this vacuum what could he do but brood & think dark thoughts? Emotionally he was a husk of a man.

Latifi’s life was completely destroyed in the catastrophe of 1947, but something survived the ravage. That was his compassion for the needy & the animals. Since his early youth in Ludhiana he had been a philanthropist & a lover of animals. He paid the fees of several poor students of the Islamia School where he had been educated. Many families in need of help received regular grants from him. He patronized & gave financial assistance to a large number of Urdu magazines & journals, especially those issued by Akhtar Shirani & Hafeez Jullundheri & their friends in Lahore in the 1930s & early 1940s.

After 1947 his personal circumstances put a stop to these demonstrations of public service & human sympathy. There were periods when he went hungry for days. I was too young to inquire into his sources of income & my friends had no idea how he supported his wife & a little daughter. It is possible that some of his friends helped discreetly. But there is no doubt that his lifestyle was wretched.

Even in these conditions, however, his compassion for God’s creation did not wilt. Whenever he had a little money he came to the rescue of those whose misfortune exceeded his own. He would stand outside a tandur (kind of a food stall for the dregs of society) & pay for the bread & dal consumed by the beggars. Once I saw him buying 30 or 40 breads which he carried in a makeshift bag. He roamed the streets around Anarkali, distributing these breads among the beggars & the needy.

His sympathy knew no limits when it came to animals. Eyewitness accounts have been recorded by Ashiq Batalavi, Bari Alig & Intizar Husain of how Latifi fed the house sparrows & suppressed his hunger to satisfy the needs of stray dogs. Intizar Husain says he once saw from the top of a bus on Ferozepur Road a tall man covered in a green overall surrounded by a flock of sparrows whom he was feeding. The birds were so intimate with him that they were perched on his head, shoulders & stretched out arms.

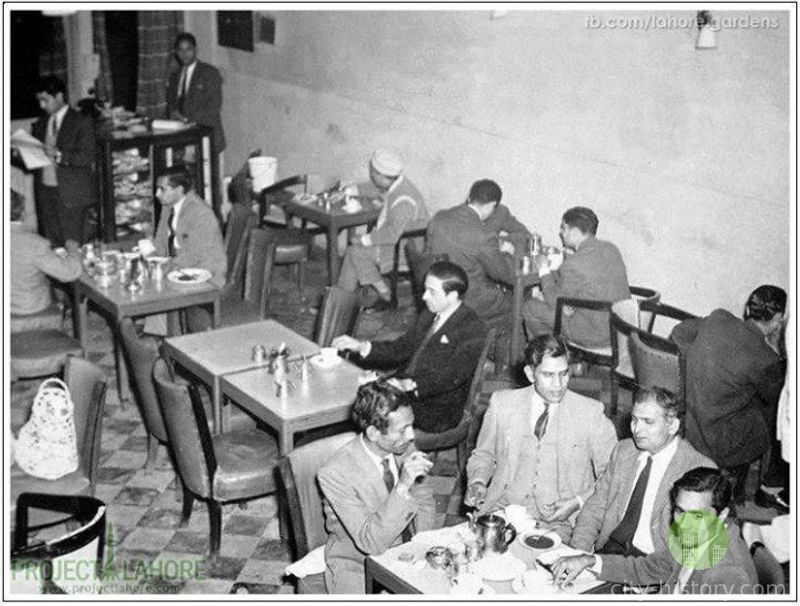

One evening Latifi & I were sitting in the Coffee House at the table on the left of the entrance & next to the window. We were in the middle of a discussion on the literary journals of the 1930s when suddenly, as if a telepathic message had reached him, he fell silent in mid-sentence & his gaze shifted from my face to the piece of lawn outside between the service road & the Mall. I too looked outside, but noticed nothing extraordinary. Then he turned to me & said, “Can you order two slices of bread? No butter on them.” I summoned a waiter & placed the order. When the slices arrived he picked them up, said “I will be back in a minute”, & walked out of the Coffee House. Nonplussed & intrigued, I let my eyes follow him. He went to the centre of the grassy plot, stopped under a small tree, & began to break the slices into small crumbs. Immediately a dozen sparrows flew down from the tree & alighted on the grass near his feet. For five or ten minutes he fed them the crumbs, smiling & talking to them.

When he rejoined me I asked him smilingly, “What was that? Did the birds send you a call which I didn’t hear?” In a serious tone he replied: “The shades of evening are falling. The sun is about to set. Birds never linger when the light begins to fail. This is the time when they have the last morsel of the day before flying to their nests. When I came here I had noticed a few sparrows flying around that tree. While talking to you it suddenly occurred to me that perhaps they had not had a fill of their food & soon they would leave for home. There are no crumbs or feed for the asking on the Mall. I thought I must not let them retire hungry. Hence the slices I requested you to order. I am sure they were happy to be fed. You couldn’t hear through the thick glass, but they were chirping cheerfully.” I could see how happy he was, but I didn’t say anything. There was nothing to say. I felt so small in his presence.

Ashiq Batalavi tells a more moving story. He was then living in a house on Temple Road a little short of the Safanwala Chowk, next to Hameed Nizami’s house. He had known Latifi since before 1947 & Latifi called at him frequently. The two had so much in common to talk about. One day Latifi arrived a little after breakfast time. “Have you had your breakfast?” asked Ashiq. “No”, replied Latifi. Ashiq doubted if Latifi had had his dinner the previous night. Therefore he asked the cook to make three parathas & an omelette for Latifi. The food was served & Latifi began to eat. After five minutes Ashiq went to his bedroom to fetch a book which he wanted to show to Latifi. It took him a few minutes to find the book, & when he returned he saw that the three parathas had disappeared. He wondered how Latifi could have polished off the entire breakfast with such speed. Poor fellow, he told himself, perhaps he had had nothing to eat for some days & had now gobbled down everything before him. While drinking tea he noticed a bulge in Latifi’s jacket pocket. Oh! I see, he thought, his family must be starving & he is taking a part of the breakfast home to feed them.

Soon after that Latifi left. A few minutes later Ashiq came out & started walking towards Malik Barkat Ali’s house who also lived on Temple Road on the opposite side. He was near Sir Abdul Qadir’s house on the right side of the road when he saw a strange sight. Near the gate of Sir Abdul Qadir’s bungalow Latifi was crouching on the footpath. Before him on the ground was spread his handkerchief on which lay the two parathas he had quietly removed from the table into his pocket. Next to him was squatting on his hunkers a stray dog with his ribs outlined on his body, & Latifi was feeding him with pieces of paratha, actually putting morsels in the animal’s mouth. Ashiq stopped just long enough to be sure that his eyes were not deceiving him. Then with tears in his eyes he crossed over to the opposite footpath & went his way.

Several days later Ashiq inquired gently from Latifi about this incident, & without any embarrassment Latifi blurted out the truth. What he said shook Ashiq to his core. Latifi’s explanation was simple enough, given his supreme compassion for animals. When he was coming to Ashiq’s house he had noticed two emaciated dogs lying on the pavement. He bent down to pat them & found how weak & thin they looked. But he had no money to buy food for them. He himself had not had a square meal for two days & the dogs’ plight pained him. At Ashiq’s house he ate one paratha to appease his own pangs of hunger but the thought of the straving dogs stopped him from eating more. He rolled the other two parathas in his handkerchief & put the packet in his pocket. On his way back he hurried to where he had seen the dogs. Unfortunately one of them had gone away but the other was still there. He said, without any emphasis on the statement, that when he was feeding the dog with the parathas he actually felt as if the morsels were entering his own stomach & felt cheerful.

This soul, full to brim with mercy & compassion for all living beings, died of chest cancer in the Ganga Ram Hospital on 23 May 1959. Few remember him today & those like me who met him on the crossroads of life are dying. In a few years his name will not even be a memory. That is how we treat the aristocracy of our intellect, & that is why we have stopped producing the only true elite which is an index of a country’s honour & prestige.

Khursheed Kamal Aziz (KK Aziz)

Khursheed Kamal Aziz (KK Aziz)

Khursheed Kamal Aziz (11 December 1927, Ballamabad, British India – 15 July 2009, Lahore, Pakistan) better known as K. K. Aziz, was a Pakistani historian, admired for his books written in the English Language. However, he also wrote Urdu prose and was a staunch believer in the importance of the Persian language

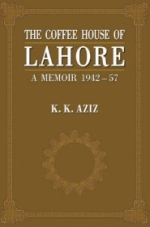

The Coffee House of Lahore: A Memoir

The Coffee House of Lahore: A Memoir

K. K. Aziz

Before his death in July 2009, KK Aziz had accomplished one mission that he had set for himself, i.e. to write about the Lahore Coffee House, the glorious nursery of ideas. Luckily, despite his failing health, Aziz finished a draft that was meant to be a shining part of his autobiographical kaleidoscope.

KK Aziz and the Coffee House of Lahore: Chris Moffat

KK Aziz and the Coffee House of Lahore: Chris Moffat

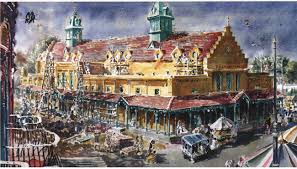

During a recent trip to Lahore, I visited the Sang-e-Meel bookshop on Lower Mall Road in search of K.K. Aziz’s The Coffee House of Lahore. Happily, the store was well stocked with the late historian’s final work, and I spent the afternoon reading the text at a table outside the nearby Tollinton Market.

Book Excerpt: Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

Book Excerpt: Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

the 1920s onwards, perhaps since event earlier, Lahore was the most highly cultured city of north India. From here appeared the largest number of Urdu literary journals, newspapers and books and two of the best English language dailies. The Mayo School of Arts was flourishing. The Young Men Christian Association was active and its premises and hall were used by all communities for literary and social activities.

Muhammad Hasan Latifi: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

Muhammad Hasan Latifi: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

He was one of those remarkable men who arrived in Lahore in 1947 as a part of the flotsam & jetsam of the partition of the Punjab. His acute sufferings began with the ravages of the great migration & ended with his death 12 years later. The story of his life needs to be told in some detail.

Zaheer Kashmiri: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

Zaheer Kashmiri: The Coffee House of Lahore by KK Aziz

A flamboyant personality, consciously outrageous, bent upon having his say on the subject of his choice, and colourful in his deportment and dress. but all this served as an outer cover (perhaps a disguise) for a heart palpitating on the plight of the oppressed and a soul full of fellowship in sorrow… As an Urdu poet his reputation stands high.

Arab Hotel Lahore: KK Aziz and A Hameed

Arab Hotel Lahore: KK Aziz and A Hameed

No description of the cultural life of Lahore can be complete without mentioning the Arab Hotel. Once the old-fashioned baithaks (sitting rooms of the orient) had gone out f use, the literati wanted a pace where they could meet, eat and talk. For those ‘orientalists’ of the 1920s the Mall was too Westernized, distant and costly. By chance they started patronizing a small, unclean restaurant on Railway Road, opposite the gate of the Islamia College.

Dr. Abdus Salam: The Coffee House of Lahore By K K Aziz

Dr. Abdus Salam: The Coffee House of Lahore By K K Aziz

Among my contemporaries and colleagues in Government College, companions in the Coffee House of Lahore and friends at these places and elsewhere there is only one genius, and that was Abdus Salam. Salam was the son of Chaudhri Muhammad Husain, a schoolteacher of Jhang and Hajirah who belonged to Faizullah Chak near Batala Muhammad Husain was a jat and Hajirah a Kakkezai.