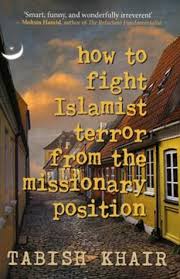

How to Fight Islamist Terror From the Missionary Position

Tabish Khair

|

|

Do you remember some Muslims’ violent reactions to the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten’s decision to print abusive cartoons of Mohammed in 2005? Or the early assumption by many sections of the media that the 2011 shootings actually perpetrated by Anders Behring Breivik were the work of Muslim extremists angry with Norway’s role in the war on terror? These moments showed the world that Scandinavia is equally as bound up with issues relating to Islamism and Islamophobia as are other parts of Europe that have far higher populations of Muslims. This brilliant new novel by Tabish Khair explores such topical issues, as well as more personal themes of love and imperfection, literature and life, city and country. How to Fight Islamist Terror from the Missionary Position’s tight plot and its accelerating accrual of clues and tension mean that the novel inevitably invites comparison with popular Scandinavian crime dramas such as The Killing, Borgen or The Bridge. Like his young protagonist, Khair teaches literature at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, but there the similarities end. Set in 2010-11, the novel culminates in a terrorist incident said to have occurred in this sleepy Danish city. After the apparent act of terror, our unnamed Pakistani narrator, his Hindu best friend Ravi, and their religious Indian Muslim landlord Karim find themselves caught up in suspicion and media attention. The narrator and Ravi begin to question how much they really know Karim, who, as well as owning their decrepit flat, also lives with them (when he is not disappearing on mysterious assignations). Handsome, clever and rich, the irrepressible Ravi has been attracted to Karim’s domestic religious gatherings because he feels that the landlord and his followers: discuss matters of significance and do it honestly: how to make sense of the world, how to make it a better world. They still have a conscience, these young men and women, not just a bank account. The narrator, who grew up in Karachi post Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamist regime, is less impressed with the view, as he puts it, that ‘the Quran is the final hand-autographed word of God’. When he refuses to dismiss out of hand the idea that Karim could be a terrorist, Ravi only half-jokingly calls the narrator himself a fanatic. This word ‘fanatic’ recalls Hanif Kureishi’s short story and film My Son the Fanatic, both of which texts similarly play with the term as an adjective that can be applied to secular fundamentalists as well as Islamists. However, whereas earlier chroniclers of Muslims’ place in contemporary geopolitics like Kureishi only vaguely sketched out the attractions of Islamism, this novel understands very well what might bring an alienated migrant to an extremist religio-political position. Despite the weighty subject matter, this is also a very funny book. Whether it’s the protagonist and his best friend Ravi affectionately calling each other ‘bastard’, a description of some of the humiliations of IVF, or two Danish men of very different sizes being known as ‘main and subordinate Clauses’, the novel is full of good jokes. I would strongly counsel against doing as I did and reading this on a flight to Pakistan. You will first of all irritate fellow-passengers with your uncontrollable laughter, and secondly you will have your work cut out explaining the title when you pass through Customs. Khair satirizes Denmark’s minimalist home decor, its monoculture, and the very little Little Mermaid statue in Copenhagen. He also sends up the perils of dating in different national contexts. The two main protagonists have a theory that 80 per cent of Danish women won’t date brown men, while the other 20 per cent only goes out with non-whites. The narrator and Ravi rightly feel that each type of woman is as bad as the other. To escape from a double date with just such a duo, the narrator exploits the girls’ cultural ignorance by ringing Ravi from the toilet and fabricating an emergency: I mumbled a 1960s Bombay film song into the receiver. He replied gobbledygook in Hindi, with a few suitably intonated English words — especially ‘hospital?’, ‘hospital!’ ‘hospital’ — thrown in. Yet Ravi finally thinks he has hit the jackpot and found a woman who neither exhibits colonial desire nor racist repulsion towards him. He falls histrionically in love with Lena, an affluent, sylphlike Dane, while the narrator has a less romantic affair with a curvaceous single mum who will only consent to sex when her son is in bed and if the act is performed on a towel ‘for the easy elimination of evidence’. When Ravi starts to become impatient with Lena’s Danish perfection and the couple run into problems, there is a striking example of Khair’s beautiful writing style in the depiction of ‘those weeks when his hands were humming-birds hovering over the flower of his mobile’. In some ways this is a campus novel, which richly evokes the bars, seminar rooms and theatres of Aarhus’s campus, and the relationships between academics and students that play out there. Perhaps unsurprisingly given both Khair’s and the narrator’s profession as English Literature lecturers, this is also fiction about fiction, replete with references to other texts. In addition to the long ‘How to…’ title’s proximity to that of Mohsin Hamid’s new novel How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, Khair’s novel also alludes to the self-help genre through the appearance of an ex-girlfriend who periodically advises the narrator on the form his novel should take. In addition to cheeky hat tips to T.S. Eliot in the chapter ‘Lilacs Out of the Dead Land’, and to Tayeb Salih and Sam Selvon in relation to migrant masculinity and sexual politics, there is also an almost postmodern moment at which Khair himself makes an appearance, as author of the story ‘A State of Niceness’. This is a fast-paced, hilarious novel that nonetheless has sufficient depth to withstand several re-readings. If there’s any justice, it’s going to be as big a hit in Euro-America as it has been in Khair’s home country of India. Claire Chambers | 25 Feb 2015 | Huffington Post

|

Tabish Khair

Tabish Khair