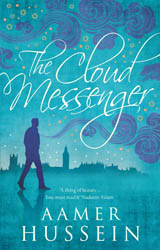

The Cloud Messenger

Aamer Hussein

Paperback: 203 pages

|

‘Each life is an encyclopedia, a library, an inventory of objects, a series of styles and everything can be constantly shuffled and reordered in every way conceivable’ – Italo Calvino At the end of The Cloud Messenger (TCM), Aamer Hussein gives a biographical account of his life in a few short paragraphs which he ends in the statement: “My novel is the story of some of the paths I might have taken. The characters and most of the situations here are imaginary.” The reason for this is perhaps the fact that the novel, narrated in part in the first-person narrative style, could be (and has been) misconstrued as “autobiography”: perhaps the least interesting thing a reviewer could say about this tour de force of a novel. Over the two decades of his literary life, Aamer Hussein’s sophisticated and complex re-working of ideas of traditional ‘novel’ and story forms is a subject worthy of study in its own right. He is not merely a writer, but a literary innovator who has single-handedly given Pakistani literature in English an overhaul, taking it into the realm of post-modern literary discourse. This is a realm that espouses ideas of deconstruction, welcomes non-linear narrative forms and as such is a revolt against objectivism, rationality and the metanarratives which have guided enquiry. TCM is therefore closer to the formulation, autofiction, which was coined as recently as 1977 by French writer and critical theorist Serge Doubrovsky in writing his novel Fils. Aamer Hussein’s protagonist is Mehran, whose life is depicted from his early childhood in 1960′s Karachi through to his adulthood in London, ending in 2010. French thinker and writer Michel Serres once said: “The self is a patchwork resembling a Harlequins coat, a badly stitched tatter, a conjunction of adjectives.The self is “a mixed body: studded, spotted, zebrine, tigroid, shimmering, spotted like an ocelot, whose life must be its business”. This loosely constructed idea of self comes closest to describing the creation of Mehran and his life within the novel. His past is interwoven with the pasts of his ancestors and his ancestors ancestors, sewn in with folk stories, mythologies and stories of the land. At the same time, however, Mehran is jumping from place to place, from story to story within the main novel through Italia, Iran, Argentina, India, Pakistan; keeping track of details becomes unnecessary as a mysterious propulsion created by the power of the language keeps one moving through the ultimate restlessness of the narrative and indeed the restlessness of the characters. “…countries, they became shadowy but remained beloved, like people from a well-loved but half remembered childhood book: or even more like those leaves or petals placed between the pages of a book, which elicit a twinge of longing but don’t immediately remind you of what it was you wanted to save, petal, leaf or page… “ The characters – particularly the female ones – surrounding Mehran are all being bathed in some mystical glow. Recurring thematic layers create a rhythm like that of sufic chants, becoming a wider emanation of Mehran’s psyche, and forming the novel’s psychogeography. His mother tells him stories of, “the exiled man who asked a cloud to carry messages to his beloved in the city,” and would “sing the words of Amir Khusro, the Songbird of Delhi, words that seemed to echo Kalidasa”. Later Mehran himself discovers, in a small book shop in Indore, Kalidasa’s plays and poems, ‘Shakuntala’ and ‘Meghaduta’ (the story of the cloud Messenger), which in turn are quoted within the novel. The latter half of the novel is coloured by three key relationships of the protagonist, adding another complex layering to the restless nature of the text, exploring how questions of love, longing and intimacy can be answered for a man such as Mehran, who can be summed up in his own words: I had learned that most people lived for work or their families, and since I didn’t want to do either I thought that at least I could see other landscapes, other skies. His great love Marvi acts as a symbol of loss, that pervades the novel: loss of home, loss of love, loss of self, transforming TCM into, above all, an anatomy of melancholy. By the time this verse is quoted before the penultimate segment: “Would that I could go home again, One realizes that there is no ‘home,’ to go back to, neither for Mehran nor for the exile, and home remains an ideal. The French thinker Paul Virilio argues that the results of the erosion of ‘home’ are spatial and temporal disorientation, and a deconstruction of the real environment, which it could be argued are evident in TCM. In light of this,Virilio talks of the new centrality of the body as a home within space, inextricably linked and mutually influential. This then, is where we leave Mehran, as a body in space. It is no coincidence that one turns to the French in talking about Aamer Hussein’s work, for his writing displays a consistent and recurring desire to challenge the boundaries of fiction, questioning the very foundation stone of the enterprise. TCM features amongst some of the most innovative writing in contemporary literature placing Aamer Hussein at the frontiers of literary possibility. Sascha Akhtar

Reviews Aamer Hussein on ‘The Cloud Messenger’, The Paris Review Stevie Davies, The Independent Manasi Subramaniam, Asian Review

|