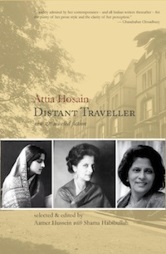

Distant Traveller: New & Selected Fiction

Attia Hosain

Paperback: 234 pages

|

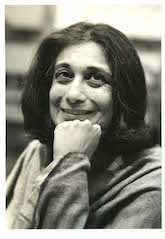

This book is a fitting tribute to an important but all but forgotten woman IndoAnglian fiction writer who sensitively chronicled the complexity of life in the times of the British Raj and the early years of Indian Independence in the novel, Sunlight on a Broken Column. Now in the centenary year of her birth and fifteen years after her death, when Attia Hosain remains not much more than a piece of literary quiz trivia, comes this collection of some of her hitherto unpublished works along with a reprint of some stories from her neglected collection of short fiction, Phoenix Fled (1953), lovingly put together by her daughter Shama Habibullah and fellow expatriate Pakistani novelist Aamer Hussein.The edition opens with the daughter’s loving account of Hosain’s unique eventful life of Nawaabi privilege, resistance to feudal patriarchy, post Partition displacement to England and cautious literary goals, and concludes with the friend’s comprehensive and incisive assessment of Hosain’s contribution to and influence upon literature written in English from the Indian subcontinent from mid twentieth century to the present. It is also happily appropriate that this project of drawing Attia Hosain out of oblivion and neglect has been enabled by the Feminist Publishing house, Women Unlimited. The misogynistic forces, which have been identified by feminist scholarship as discouraging and devaluing female literary output over the ages, are being countered and corrected by such initiatives.

The recuperation of Hosain’s works proves an important case in point. Attia Hosain’s essay, ‘Deep Roots’, first published in 2000, included here reveals her serious engagement with her subject matter and the craft of fiction. She addresses various problems such as cultural pluralism in India, tradition versus modernity, use of English to represent Indian subject matter, identity problems of expatriates, relation between art and life and social function of literature. Aamer Hussein has rightly labelled her work as ‘a crucial part of a flowering of South Asian writing in English that saw the emergence of talents such as Rushdie and Bapsi Sidhwa, Vikram Seth and Rohinton Mistry…’ following it up with a long list of writers including Arundhati Roy, Amitav Ghosh , Kamla Markandeya, Santha Rama Rau, Nayantara Sahgal, Anita Desai and many many others. The excerpts from Hosain’s unfinished novel, No New Lands, No New Seas, are a veritable goldmine. It is a great loss to literature that she did not complete it. The writing displays great maturity in the handling of expatriate existence in England in a compact, luminous and witty prose style. There is a fascinating range of characters from Murad, the Westernized liberal Indian Muslim who plans to return to his native Lucknow, to the former leftist idealist academic Isa with his wife, British mistresses and the bitter wreckage of his revolutionary dreams, to the widow of Isa who despite her traditionalism has so effectively adapted herself to the British environment. Most fascinating is an account of an Indian restaurant in London run by a Bengali called Khadim from East Pakistan, who changes his own name on advisement for better business to Chaudhary, and changes the signboard of his restaurant again and again according to changing times from ‘The British Indian Restaurant’ in 1930s, to ‘the Great Indian restaurant’ in the 1940s fervour of Independence struggle, to ‘the Great Indo-Pakistan Restaurant’ in the post Partition climate of 1947-48, displeasing Pakistani expats by inclusion of Indo, almost to ‘The Great Commonwealth Restaurant’ in hope an overarching inclusive umbrella, and finally to ‘The Pride of Asia’ (with plans to include ‘Afro’ in the future) in the 60s. The last move finally earned him great popularity and material success by appealing to various communities. This passage reminded me of VS Naipaul’s similar rendering of the changing nomenclature of Asian Indians in the Caribbean islands in ‘The Overcrowded Barracoon’ to capture the complex chaotic impact of historical and political movements on diasporic communities. Perhaps it was Attia Hosain’s deep sadness at her loss of home after Partition and her subsequent rootlessness, despite her comfortable supportive Progressive Left literary circle in London that prevented her from completing this excellent work. I hope against hope that some more chapters are unearthed in the near future. The five hitherto unpublished stories, dating back to the ’30s when Attia was still living in India, may be viewed as ‘juvenilia’. They are interesting in that they record a young girl’s burgeoning attempts to break out of a privileged, traditional yet repressive milieu and confront a world entrenched in social inequities of the feudal system and replete with waves of political upheavals. The stories show a keen observation of social detail and a great linguistic facility with English. The rereleased stories from Phoenix Fled constitute a more polished form of her juvenilia. They display the influence of British modernist writers like Katherine Mansfield, Lawrence and James Joyce in their sharp luminous metaphorical textures and tableau like quality with absence of strong story lines. The stories possess a lyrical quality through the creation of atmosphere peopled with poignant and mostly dispossessed, persecuted characters existing in rhythmic movements. My favourite story is ‘Phoenix Fled’ which presents an ancient storytelling grandmother refusing to leave her home even in the face of an imminent communal attack and jealously guarding her doll’s house from the rioters. Attia Hosain’s stories of subaltern life show her affiliation with the British Progressive Left intellectuals who flirted with Communism, but whose Liberal Humanism and compassion were devoid of a consideration of class, race, caste or gender distinctions. Thus Hosain’s portrayals of poor exploited peasants, old neglected servitors, persecuted child wives, sexually abused women, victims of communal violence and such like tend to have an upper class voyeuristic quality packaged with an aesthetic veneer. The stories unfortunately exude an unrelieved atmosphere of grey despair, where no solutions are offered. The social criticism, condemnation and satire become a statusquoist end in their ‘no exit’ scenarios. Of course this is a quality that is prevalent in most IndoAnglian fiction of today. These writers, fitting the bill of Ngugi Wa Thiongo’s ‘Nationalist Bourgeoisie’ category, have so imbibed the white man’s ideology and become so out of touch with their own grass root cultures that they are trapped in endless circles of darkness. Gender and expatriation redeem Attia Hosain from the total complacency of her successors. This book is a very enjoyable and rewarding read Dr Mita Bose is associate professor in the department of English, and vice principal, at Indraprastha College for Women, Delhi University. She received her PhD in English from Kent State University, Ohio, USA. She has been teaching English Language and Literature at Delhi University since 1972. She has also participated in the ELPC programme held at the ILLL, DU. ReviewsAttia Hosain: Unplugged – Rakhshanda Jalil Celebrating Attia Hosain 1913-1998 – Ritu Menon and Aamer Hussein

|

Attia Hosain

Attia Hosain “Storm” by Attia Hosain

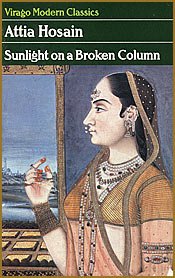

“Storm” by Attia Hosain Sunlight on a Broken Column

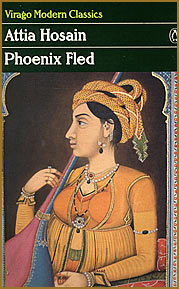

Sunlight on a Broken Column Phoenix Fled

Phoenix Fled

Hosain 1913-1998

Hosain 1913-1998