Face of a Friend: Ahmed Ali 1910-1994

K. Natwar Singh

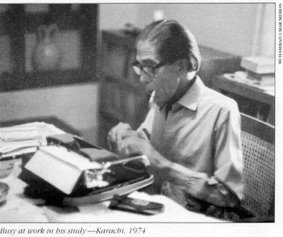

Busy at work in his study – Karachi 1974

Ahmed Ali belonged to that rare breed of men who are straightforward in their dealings with themselves. He was humane, humorous, warm- hearted, had a gift for friendship and was so upright that it was impossible to withhold admiration. Voltaire has written somewhere: “Aimer et penser: C’est la veritable vie des esprits” (“To love and to reflect: that is the true life of the spirit”). That about sums up Ahmed Ali’s life, which was not by any means a holiday. Partition broke it into two. Then he fell out with the Ayub dictatorship and resigned from the Pakistan foreign service and began reconstructing his life all over again. His wife was an early victim of cortisones and suffered stoically for decades.

Many enduring friendships I owe to E.M. Forster, who asked, “Have you met Ahmed?” That was forty years ago. I had not heard of Ahmed, let alone read anything by him. Twilight in Delhi was recommended and I came under its spell.

Two years later, in July, I met Ahmed Ali in Peking (as it then was). The Chinese were celebrating George Bernard Shaw’s centenary and Ahmed Ali, who had before Partition spent some time in China, was an honored guest.

We next met twenty-four years later in Karachi, when I was ambassador to Pakistan. In between we had collaborated on a book on E.M. Forster, which was published in New York by Harcourt, Brace to mark Forster’s 85th birthday.

Soon after Ahmed Ali’s second novel, Ocean of Night, was published in London. He sent me a copy in New York. I was disappointed and wrote to him about it. The book was written by an artist, but was not a work of art. Ahmed Ali replied at some length, touching on serious aspects of literature, the part good and evil play in our lives, and how helpless we are in warding off evil. He wrote from Karachi on 26 July 1964:

Ocean of Night is out, but no reviews seem to have appeared so far. I am sorry you did not care for some of the characters. But then, as you may have noticed, it is primarily a one-person novel, and the problem posed necessitates the sleepiness of some Lucknow characters—decay of the social order, and the clash between feudalism and a more modern attitude and way of life. … But I grant that its canvas is limited compared to Twilight in Delhi, though in the same measure deeper, looking inwards, as the earlier one had looked outside at wider fields. In the next novel the problem would be different: of good and evil against the background of diplomatic life in Peking. In my experience, it is evil that triumphs in spite of Christ and Gandhi and even God. But I do not know if I shall even be able to write it, situated as I am in my present difficult circumstances.

He goes on in the same pessimistic, even fatalistic mood:

Each one of us works out his destiny, preordained as in the doctrine of karma or running its course in the material conflicts of existence in this world. And no one can help when the tide has turned against a man, and the wheels of time grind everything down to indistinguishable dust.

But he bounced back.

I kept in touch with him and after arriving in Pakistan, I contacted him and went to Karachi to be with him on his 70th birthday on 1 July 1980. When he came to Islamabad, he always made it a point to spend some time with me. He was generous in his review of my book on Suraj Mal (1707-1763) for the Times of India. He even wrote a poem about me, which he read out at a farewell reception given for me in Karachi by Mani Shankar Aiyer, our consul general.

A few days before I left Pakistan in March 1982, Ahmed came to Islamabad, to receive from President Zia-ul-Haq the Hilal-e-Pakistan (if I remember correctly). I chided him, “Shame on you Ahmed, succumbing to this dictatorial embrace, having rejected an earlier one.”

He replied in Urdu, “Khuda-parast insan hai, larkiyon ke pichey nahin bhagta.” (“God-fearing man. Does not chase girls.”) In nine words Ahmed had summed up the characters of Zia and several of his predecessors.

He spent the better part of the afternoon with me. He was thin as a stick, but bright as a button. We talked about his translation of the Qurann. About Ghalib and Mir—his favorite poets. And about Mulk Raj Anand and Raja Rao. He made fun of Pakistani humbugs, who got on their hind legs to deny their Indian past. Ahmed was proud of it in a personal and profound way. It was a part of his heritage.

Yet he did not wish to visit Delhi. I invited him several times. He declined, “Which Delhi, Natwar? Let me live on my memories.” Now, I too shall live on my memories of Ahmed Ali, one of God’s fragrant creations.

[Gratefully reproduced from Hindustan Times, 24 March 1994]