Book Excerpt: Seven Heavens by Samim Ahmed

Nana, Grandfather, had a dream the night before Runa’s mother was born. He was prone to changing the story of the dream at different times. Sometimes he said that a dervish wrapped from head to toe in a black smock bisected by a milk-white beard had told him, today’s the day your family gets an heir. Nana also claimed that it wasn’t a dervish at all; the voice did not reveal whether the speaker was a man or a woman. The garments were unusual too, for it appeared that the person wearing them had arrived from the deserts of Arabia to this unknown village in Bengal. In a genderless voice the figure had told Nana, the boy who will be born in your house today will enable sheikhs to hold their heads up higher. Nana had another version too, in which a boy child addressed him as Abbu. The dream had several variations, each of which changed as Nana grew older. But Runa had heard from her Nani, Grandmother, about the different kinds of dreams that Nana would have about the birth of Runa’s maternal uncle, her Maamu, before her mother was born. Nana had had to wait for a male child. By that time the stories of his dreams would change repeatedly. But what never changed was the presence of a male child at the centre of his dreams. Nani’s labour pain came on the eve of the dawn on which Runa’s mother was born. She was taken to the permanent labour room in the house. When Runa and her brothers and sisters grew up, they named this room the German Hussain Private Nursing Home. It was named after their Nana. When Nani’s pains worsened, Nana felt a violent pressure on his bowels. The toilet for men was some distance from the house. As he was on his way there with a pot of water, he encountered a young man standing by the tank next to the toilet. In the half-light of dawn, Nana recognised him as Robin. But strangely, Robin’s elbows, knees and ankles were all pointing in the wrong direction. Or, it would be better to say that Robin’s head seemed to be set front to back. When Nana saw this he could not control his bowels any longer. But Runa’s courageous Nana, who was said to go for a shit on horseback, noticed as he began to scream Robin’s name that Robin had started walking with his face towards him. But the distance between Robin and Nana kept growing. Nana was brought back home unconscious. The house was full of women from the neighbourhood, along with the midwife. The midwife was the only Hindu woman present. Only the women from the tribal Hadi families worked as midwifes hereabouts. She had been by Nani’s side, sleepless, since last evening. Nani had given birth to a child. She was lying unconscious in a corner of the labour-room. Then Nana was brought in, his body frozen with fear.

Nana, Grandfather, had a dream the night before Runa’s mother was born. He was prone to changing the story of the dream at different times. Sometimes he said that a dervish wrapped from head to toe in a black smock bisected by a milk-white beard had told him, today’s the day your family gets an heir. Nana also claimed that it wasn’t a dervish at all; the voice did not reveal whether the speaker was a man or a woman. The garments were unusual too, for it appeared that the person wearing them had arrived from the deserts of Arabia to this unknown village in Bengal. In a genderless voice the figure had told Nana, the boy who will be born in your house today will enable sheikhs to hold their heads up higher. Nana had another version too, in which a boy child addressed him as Abbu. The dream had several variations, each of which changed as Nana grew older. But Runa had heard from her Nani, Grandmother, about the different kinds of dreams that Nana would have about the birth of Runa’s maternal uncle, her Maamu, before her mother was born. Nana had had to wait for a male child. By that time the stories of his dreams would change repeatedly. But what never changed was the presence of a male child at the centre of his dreams. Nani’s labour pain came on the eve of the dawn on which Runa’s mother was born. She was taken to the permanent labour room in the house. When Runa and her brothers and sisters grew up, they named this room the German Hussain Private Nursing Home. It was named after their Nana. When Nani’s pains worsened, Nana felt a violent pressure on his bowels. The toilet for men was some distance from the house. As he was on his way there with a pot of water, he encountered a young man standing by the tank next to the toilet. In the half-light of dawn, Nana recognised him as Robin. But strangely, Robin’s elbows, knees and ankles were all pointing in the wrong direction. Or, it would be better to say that Robin’s head seemed to be set front to back. When Nana saw this he could not control his bowels any longer. But Runa’s courageous Nana, who was said to go for a shit on horseback, noticed as he began to scream Robin’s name that Robin had started walking with his face towards him. But the distance between Robin and Nana kept growing. Nana was brought back home unconscious. The house was full of women from the neighbourhood, along with the midwife. The midwife was the only Hindu woman present. Only the women from the tribal Hadi families worked as midwifes hereabouts. She had been by Nani’s side, sleepless, since last evening. Nani had given birth to a child. She was lying unconscious in a corner of the labour-room. Then Nana was brought in, his body frozen with fear.

As soon as word spread of Nana’s falling unconscious, the kaviraj arrived from the nearby market town. After all, Nana was the local president of the Congress party.

The doctor prescribed medicines for Nana, and suggested all kinds of nutritious food to revive him. Meanwhile no one could be found to read the Azaan after the birth of Nani’s child. Neither the newborn baby nor the mother could eat until the Azaan was read. Eventually a solution was found. Tentuli, the permanent farmhand for the family, arrived to tend to the cattle. He bathed and offered the Azaan. Then an old woman from the neighbourhood poured a drop of honey into the baby’s mouth. When Nana came to, she was given tea with jaggery. Runa’s mother was born on a Thursday. The day of Lakshmi in the month of Shravan. The Bengali year 1348.

It wasn’t long before the formidable Maulana sahib from the next village arrived. Nana had been made to lie down on a mattress covered with sheets in the veranda. Maulana sahib was given a chair next to him. He asked in detail about the events that had taken place. Nana told him everything slowly – what he had dreamt, his glimpse of the creature named Robin with the reversed ankles and knees in the half-light of the monsoon morning, and his resultant defecation in his cherished Ismail lungi. Having heard him out, Maulana sahib said, you dreamt all of this, German Mian. These events took place at dawn on Thursday, which means the nymph has set her sights on German Mian. This creature attacks while her victims are passing passing urine and stool. You have to be very careful the next ten days. But the influence of this jinn-nymph will persist even after that. The evil eye of the nymph will keep troubling you in the form of all kinds of illnesses. Sometimes your back will feel as though it is breaking. At other times it will be an excruciating headache. A thousand nightmares await you because of your ill fortune.

The matriarch of the family, Runa’s great aunt, her Mejo Nani, opened the door a crack and said, tell us how to cure this illness. We will spend as much as required. Just make the arrangements. The Maulana said, all right Bhabijaan, a black cock, even yellow will do, mid-sized, five chhataak ghee, some mehndi leaves and half a bhari of silver – you have to make these four offerings to the poor. After the afternoon Namaz I will send an amulet. Chant Bismillah and read three verses, and then fasten the amulet to Bhaisahib’s right arm above the elbow with black thread.

Very well, said Mejo Nani and went off to make the arrangements.

Maulana Sahib asked Nana, how do you feel now? Nana told him:

So Maulana, I’ll be cured with those offerings? Ramlochan Kaviraj has prescribed medicines. I should be eating those things you mentioned, to gain strength. And you say they should be given to the poor? Do you know how much half a bhari of silver costs? I believe in amulets, I know that jinns and nymphs cannot come anywhere near me if I wear the lord’s discourse on my body. What is this that you Muslim League people are doing! Is this the faith of my ancestors, if this the Deen, the path, that they brought from Arabia! You’re not an ignorant village Maulvi, you’re a Maulana with a degree. How can you say such things! You claim you want Pakistan, but your Hindu customs refuse to go away. Not that it’s your fault, each of your leaders has crossed the line, they’re worse than infidels.

Maulana smiled. A strange smile. Whose significance was soon revealed in his own words:

Whatever you may say, German Mian, the Muslim League will definitely win. You people can keep saying whatever you like. The Tabligh is inevitable. All the common people will follow the learned leaders. We have plenty of leaders who are learned.

Nana said:

Yes! You have Maulana Thanvi and Shabbir Usmani, with Jinnah as your head. Naturally you will be uncompromising. This doesn’t surprise us. But if the country is split, where will you and I go, abandoning our paternal homes and farmland? That leader of yours, Jinnah, do you know what he said, that he will go through martyrdom for a majority Muslim state. It doesn’t matter to him if we’re murdered. He will let twenty million of us be martyred on the streets and build Pakistan on our corpses.

– Have you heard of Kamal Pasha? The one about whom they said Kamal tune kamal kiya bhai – what a wonder you have wrought, Kamal. If Mustafa Kamal could create a Turkey, why can’t we? The leaders of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind have only been badmouthing Jinnah. They refuse to understand that an Islamic state can easily be created out with the Muslim-majority provinces, built with the fundamental faith, laws, jurisprudence and rules of Islam. The Jamiat is now under the control of the Congress. They will go whichever way the Congress directs them to. What you refuse to accept, Mian, is that the Congress is the party of the Hindus.

– You know what Madani sahib has said, it’s the leaders who don’t accept Islam that want to have Pakistan. Hmmph! Ladke lenge Pakistan. We’ll wrest Pakistan by force. Madani has written that if Pakistan is indeed formed, its people will starve. How will its economy be created? Can you tell me that, Maulana? The Jamiat believes that if Pakistan is created it will become the factory of politics for England and Russia one day. I think so too. Can a man like Thanvi understand all that vexes us? The Muslim League does not have a single Alim, a single learned leader, who can divert you from the path that leads away from the Sharia and think of the welfare of our nation, our Qaum.

– Whom do you consider a learned man, German Mian? Madani – you think Madani is learned? What does he know besides enmity with the British? He has no concern for Muslims. He will only continue his holy war against the British. And the Congress’s Abul Kalam Azad! He is neither a politician nor learned. Put all your wise men on one pan of the scales, we’ll put our Thanvi sahib on the other. Check for yourself which way the scales are tipped. The formation of Pakistan is inevitable.

Now the second eldest of Runa’s great uncles, her Mejo Nana, entered. He was the head of the family. The eldest one lived in Dhaka, where he worked at the post office. In his absence, it was the second brother, Mejo Nana, who took care of the estate. Calling out to the Maulana, he said:

Now what, Maulvi? Has Jinnah sahib come up with anything new? Have you managed to draft German to your cause? I don’t think he will join your League or anything. Can your people finance his three horses and Ismail lungis? We do that. Ha ha ha. While the Mian was seeing a ghost on his way to shit, he had a daughter. Now that you’re here, give us a suitable name for her and find out her star sign. We’ll look after your needs.

Runa’s Nana’s face turned pale. He seemed to have set eyes on Robin again, and appeared ready to repeat his earlier act after that vision.

The Maulana said:

This means the girl was born between five and six in the morning. On a Thursday. This girl’s astrological sign is Zehal, what you refer to as Shani in Bengali. Call her Zahra. She will be quite dark-skinned. But her life will be wrapped around God, her lifespan is long. She will have a lovely voice. Your niece will have a clear heart.

Mejo Nana took a two-rupee note out of his pocket and gave it to the Maulana. Keep this, he said. Meanwhile the permanent farmhand Tentuli appeared and asked Maulana sahib:

Huzoor, rice was two annas a kilo last rains, how could it have become three annas this time? If this is what coarse rice is going to cost, what about fine rice? Tell them to lower the price. Can’t afford it. We have children at home, what will we feed them?

Tentuli had five children. The eldest was eight. He looked after the cows at Mirad’s house. Swept and cleaned the cowshed. For which he got two meals of stale rice a day. Tentuli couldn’t possibly ask his wife to abandon the baby in her arms to work as a maid in other people’s house. His second son hadn’t been home all morning. The six-year-old boy had been to the fields and hadn’t returned. He hadn’t gone alone, though. Many of the other boys in the village were there as well. The fields were full of kochu, edible taro roots. They had sprung up some time ago. Now the earth had been softened by the monsoon rains. His second son was in the fields, digging for slugs. If he was lucky, he might get some taro too. But these things were not available every day. Many of the children in the village gathered them. Worried about food, Tentuli went to his wife. He told her, Chhoto Mian had a daughter at dawn today. I read the Azaan. I was thinking, will you go over?

Tentuli’s wife protested furiously, I’m dying with this six-month-old baby here, and you want me to work as a maid there?

Tentuli grew nervous. Then he said, did I ask you to work as a maid? Just pay them a visit, don’t people visit one another? He added with a chuckle, Mejo Mian was talking about you.

This worked almost instantly. Promising to visit them in the afternoon, Tentuli’s wife went back into the house. Tentuli shouted after her, ask Mian sahib for some rice. Just make sure he gives his word, that will be enough.

Meanwhile, prices began to rise in a frenzy. Not just poor people, even the small farmers found themselves with their back to the wall. Kerosene was unavailable. No sugar anywhere, and it was difficult to get any even at ten times the price of jaggery. Salt, oil and flour were becoming more expensive by the day. Even an entire goat did not fetch the price of a lungi.

The paddy harvest had been indifferent last year. Burma was in very bad shape. Wars were raging all over the world, which meant trouble for everyone. Some people in the village had maunds of rice stashed away at home. This was despatched to the city in bullock-carts late at night, where it was sold at twice or thrice the normal price. All this would apparently go to Madras, Ceylon, Travancore. The English government couldn’t be bothered. The leaders of the Congress and the Muslim League were silent too. They were busy ushering in freedom to the country. That was far more important than rice. German Mian’s elder brother Anwar Mian pondered over all this, assuring himself that once azaadi had been achieved, not just rice, but all items of daily use would become much cheaper. They might even be available free of cost. The new government would be run by the people of the country.

Anwar Mian spent his afternoons grooming the horses, which were a favourite of his younger brother’s. The farmhands were not to be trusted. The rascals ate up all the jaggery meant for the horses. He fed the horses their chick-pea personally, though. Never mind the oil-cakes and bran, even the grass and the hay could not be accounted for. The scoundrels pilfered everything. Someone hovering the front room caught his eye. Who was it? Tentuli’s wife, wasn’t it? Couldn’t the hussy have found a better time to turn up?

– What do you want now? Is this any time to visit?

– I’ll come whenever you want me to. There was something I had to say, but you can’t turn me down, I’ll say it if you promise not to.

– You want money, right? Come at night, I’ll give you some. The sun hasn’t even gone down and the bitch wants money. If you’re asking for money by daylight does that mean you plan to return it?

– No Mian, I didn’t come for money. I was just saying, if you’ll give me some rice tonight, I’ll come over to collect it.

Anwar Mian’s face brightened. Laughing, he said, go away. No rice or money for you. Go now.

Tentuli’s wife knew that this ‘no’ actually meant ‘yes’. She set off homewards happily. Anwar Mian said, addressing her:

Have you heard, Chhoto Bo-Bibi has been released from the labour room. Come every evening starting tomorrow and massage her legs with oil. And listen, the chhoti ceremony is three days from now, bring your children for the feast.

Tentul’s wife said ‘ji’ and resumed walking. No one from Nani’s family would come to the lavish chhoti that was being arranged on the occasion of the birth of her child. Normally the first child was born in the mother’s parents’ home. The exception in this case was because when Runa’s Nana went to his wife’s home for the ashtamangala ceremony after the wedding, he swore for some unknown reason never to set foot there again. Nor would he allow his wife to go home. Oddly enough, there had never been any pressure from Nani’s family. And no one from either family had ever pleaded with Nana to go there. Nani had accepted this without protest. Some had even heard her say that she was far happier here than she had been at home. Although the neighbours had discussed this threadbare, none of them had dared bring it up in Anwar Mian’s house. The reason for which could be either Anwar Mian’s loud voice or his bloodshot eyes.

The arrangements for the six-day ceremony had been flawless. Not even the exorbitant prices in the market could prune expenses. Several sets of clothes had been bought for the newborn, with Nani also getting a number of saris. Relatives and neighbours had feasted. None of them had come without gifts. They had arrived with presents ranging from homemade ghee to a cock and fruit for a glimpse of the child. Only one of them had brought nothing. She was neither a relation nor an in-law of Nani’s. She was from Nani’s village – her childhood friend, apparently. How could an unmarried woman travel on her own? And the less said of her family the better – imagine allowing a woman of marriageable age to travel on her own! Her house was an hour and a half’s walk through the fields.

Later it turned out that she was there to meet not Nani but Mejo Nana. After visiting the newborn she told Nani:

Please arrange for me to meet your brother-in-law. Do you remember my telling you about Asgari Begum? The Englishmen arrested Asgari a few days ago. They have burnt him alive. They’ve also put Hosenara Begum from 24 Parganas in jail. None of the people who went on the civil disobedience movement has come back. Jamila Khatun has been hanged. But never mind all that, there’s no end to it. I’m not here to tell Mejo Mian these stories. He knows everything anyway. I’ve come to him with a request.

Tell me, said Nani, I’ll send him a message. Where do you live these days? Your family has thrown you out, I know. Thank goodness I got married, or my fate would have been the same. Not that I’m particularly happy about it. It’s all destiny.

Nani’s friend smiled. You’ve heard of Majera Khatun, haven’t you, she said. She has formed a force, which I’ve joined. You recognised me easily because of the way I’m dressed now. But usually I wear thick pants, strong shoes, a thick coat and a turban to cover my hair. Nobody can tell whether we’re men or women. Our financial situation isn’t good. It would be of great help if your brother-in-law could arrange for some money for us.

Nani seemed to have guessed as much already. Don’t worry, she said, I’m sure we can get you some money. Send someone to me a week from now. I promise you that we will give as much as we can – we’ll even sell a few things if we have to. The young woman left after lunch.

Meanwhile, rice became more expensive. The price of coarse rice had risen from five rupees per maund to fifteen over the past three or four months. Some people were even selling their babies for a kilo of rice. Men and women were said to be dying of starvation in some places. Amidst all this, some strange news arrived one day. Traders were transporting rice and lentils on the narrow-gauge railway between Katwa and Ahmedpur. A group of people tried to loot them at Kurmadanga Station. Apparently they had pleaded with the traders for alms before looting them. The traders called the police. The three or four armed policemen who were on the train chased away a crowd of about a thousand people, beating them up with their sticks. Some had split skulls, and others, broken arms and legs. But still they didn’t let go of their booty. Even the most merciless beating couldn’t separate them from what they had looted. It was being said that some of them had actually died of the beating. The fingers of the dead gripped the sacks like pincers.

The government wasn’t taking any steps despite the crisis. Everyone was busy with the war. The newspapers said that the government had fixed the price of rice at five rupees and seventy-five paise. But no one was interested in following the government’s orders. The Congress stormed a rice mill in Midnapore with two or three thousand demonstrators. A large quantity of rice was stashed away in the mill. The people raised slogans – no hoarding, no exporting. Five armed guards were posted at the mill. Without panicking, they opened fire, killing three people and injuring many. About ten protestors were arrested. Leave alone reining in prices, the government paid no attention to any of this. It had lost control over the pricing of everyday items. The people from the Rice Mills’ Association were openly saying that they would not sell their produce at the level fixed by the government. They had bought the stuff at high prices, and would therefore sell even higher. This government had been in place for a long time. Fazlul Haq had become the Prime Minister of Bengal four years ago. People called him Sher-e-Bangla, the Tiger of Bengal. German Mian felt that Haq was a paper tiger, who was behaving more like a snake in the grass. Muslim leaders said that Haq sahib’s Krishak Praja Party represented peasants only by name, for actually it was the party of Ashraf Muslims, who claimed foreign ancestry. How would he look after the interests of Muslim farmers? Haq was a puppet controlled by wealthy Hindus. He couldn’t sleep at night without bowing and scraping to them. And the Hindus not only had a great deal of money, but also plenty of people to invest in them. From Burrabazar traders to the Tatas and Birlas, everyone was funding the Hindu parties. Had Haq sahib remained on the side of the Muslims, the Ispahanis would have given the Prime Minister money for the community in these times of famine and despair. But Haq sahib had fallen under Shyama Prasad Mukherjee’s spell and forgotten the Muslims. And Shyama-babu was the finance minister of Bengal. Which clearly showed how easy it was to hoodwink Haq sahib. That was precisely what Mukherjee had done. Keeping the finance portfolio to himself, he made Haq the Prime Minister. Khwaja Nizamuddin would have been a far better Prime Minister. And besides, Shyamaprasad was not only a member of the Hindu Mahasabha, but he also said nasty things about Muslims everywhere. Haq sahib pretended not to hear. His own case was complicated. At one time he had appeared to be a representative of the Muslim League, and it had seemed that his Krishak Praja Party might merge with the League. But it was different now. His activities in cahoots with the Hindu Mahasabha had marked him out as nothing but a pimp seeking power. He had done nothing for the Qaum barring friends and relatives. He had begun consorting with the Hindus at a time when all of Bengal’s Muslims were starving, and had handed over the larder keys to Shyamaprasad, who was a sworn enemy of Muslims. While Muslims lay in their beds trying to quieten their growling stomachs, Shyamababu was holding Hindu Mahasabha processions badmouthing Muslims to his heart’s content. Just a few months ago he had announced at the top of his voice at a public gathering: let Muslims pack their bags and leave India.

Why should they? Was India his ancestral property? German Mian felt a writhing anger.

Runa’s Nani emerged from the labour-room after forty days. She used to write all that was on her mind in a notebook. For two or three months now, she had written nothing. Kamrunnesa began writing all over again, although she misspelt her words, in the manner of a diary. But there was no continuity. For the most part, the things she had heard found their place, scattered and unconnected, in a notebook covered with green paper. On the first day Kamrunnesa wrote:

‘I have had a beautiful daughter. I had meant to call her Lakshmi. But he didn’t agree. Maulana sahib has named her Zahra. It is a wonderful name. Lakshmi would not have been a bad nickname for her. He said, there is great poverty everywhere, to name her after the goddess of wealth in these times would be unjust to people. There is strife all over the world.

When I was at my parents’, I heard stories about how Lakshmi turned into rice grains to save people. When a poor cowherd was sobbing out of hunger, Lakshmi gave her rice seeds. The colour of that rice was like gold, and it was fragrant. I am reminded of this story when I get the aroma of Bhimshal rice. The old woman who worked at my parents’ house used to say that Lakshmi gave just a small quantity of rice seeds – but that was enough to have the grains growing everywhere. The hills, the ponds, the canals, the fields all overflowed with the crop.

I have been eating Bhootmuri rice these past forty days. It boosts the flow of breast milk. Before my sister left our parents’ house, she used to eat Kabirajshal rice. These people have no Kabirajshal rice. It was available at my parents’ house.

Dozens of people come to this house for their meals every day. I am not inclined to turn so many people down. Mejo Bhaijan measures out the rice these days. I don’t know how all these people will manage. Rice, potato and sugar are hard to get. We have enough rice for a year at home, but how can you eat rice alone. Mejo Bhaijan has bought a maund of potatoes. I do not know how long it will last in this huge family. But then, it is not supposed to be my concern. Mejo Bhabi will worry about it. Still, if you are part of a household you have to think of these things. You have to think of the villagers too. For a fistful of rice they’re selling the animals they use to plough their fields. People are dying every day. The price of rice has risen to thirty rupees a maund. Babies in arms are being sold in Burdwan and Nadia districts. When I look at my Lakshmi, these things make me tremble. They’re selling children for five to twenty rupees. But then who will buy them, who has the money to support a child?

It seems a girl was sold in exchange for a maund and a half of rice in Birbhum. Unable to feed his wife and child, a Muslim weaver jumped into the Kansai river and drowned. His wife threw their younger child into the river. She had buried the elder child, but a lower caste Hindu rescued the him.

My friend had come. She stayed three days. He objected, but Mejo Bhaijan said she could stay as long as she liked. A couple of stories she told me didn’t let me eat at night. A woman and her mother from Agartala village under Nandigram police station in Midnapur have been widowed in a tornado. The rest of the family have drowned. The starving mother and daughter began to beg, and went all the way to Kakdwip. An accountant there offered them shelter. Giving them a room to stay in, he assaulted the daughter repeatedly. Not content with being the only one, he got others to assault her too. The evil accountant has set up a factory for her. The devil and his friends assaulted a Muslim woman the same way when she went to Kakdwip from Khulna. They gave her father a small plot of land and ordered him to remain silent. They even threatened to kill the family if they revealed they were Muslim. My friend and her group visited them in secret. The woman said, I have no family, what do I need honour for. My belly is empty, what should I keep it hidden for.

Meanwhile Netaji has left India. From his voice on the radio we know he’s alive. City people are moving to the villages because vegetables are cheaper here. So vegetables are no longer available. The Quit India movement started a few days later. He says he will join the movement. But he’s abandoned his plans for now after Mejo Bhaijan scolded him. Maulana Azad is in jail. My friend came again. This time too she was here for money. She needs the money because Maulana’s wife is in trouble. She needs help. Maulana cannot provide much money to his family. On top of which he has been jailed for a year. Maulana’s wife Zulekha Begum has no regrets about this. She has sent a letter to Bauji, saying that she had not expected her man to be jailed for a year. His exploits should have fetched him a longer term in jail. She would take charge of the Khilafat Committee in Bengal in her husband’s absence. Zulekha Begum needed money, which was why my friend was taking contributions from different people.

He says Shyama-babu has parted ways with Haq sahib. Because the government is not despatching food to Midnapore. Haq sahib’s throne is tottering too. The League doesn’t approve of him. The lieutenant governor cannot stand him. A few days later I heard Nawab Nazimuddin had got the throne. Suhrawardy was the food minister now. People thought they would get food at last. But their suffering increased. People kept dropping like flies. Tentuli the farmhand said corpses could be seen in the bushes. Neither jackals and dogs, nor vultures and hawks lacked for food now. There is no water in the ponds. No water to be had at the mosque either. Water has to be fetched from distant places. The League is feeding people free of cost at many places. They have plenty of money. The Ispahanis give them both food and cash. Ramlochan the kaviraj said the Ispahanis have apparently bought up all the rice at a high price and are hoarding it. People aren’t even strong enough to walk to free food camps. Even the leaves on the trees are wilting. There is no hope of eating them. Fuel is available but what will people cook! They’re being poisoned to death by the hyacinth from dead ponds. Mejo Bhaijan told a story about an old man from Ujjalpur who was returning home after failing to get any food. Tripping on the ledge between two fields, he fell down by the canal. Three jackals ate him alive.’

Lakshmi, meaning Zahra, was four already. Kamrunnesa, that is to say, Runa’s Nani, was pregnant again. Runa’s Nana began to dream once more. But he had changed a great deal during these years. He no longer had bitter arguments with the Maulana. On the contrary, their viewpoints had converged in many respects. Nana kept dreaming and weaving different versions of his dreams. Zahra had reached the age when her Bismillahkhani, the day she would start learning to write, was fast approaching. It had to be done at the age of four years, four months and four days. But given the state of the nation, elaborate ceremonies had all but vanished from people’s lives. German Mia had a dream on the night of the Bismillakhani. Maulana sahib had performed the ceremonies. He had spent the entire day at their house. They had long conversations. He left late in the afternoon. In the evening German Mian surmised that dreams would not spare him tonight. So he ate his dinner quickly and went to sleep on his own. In his dream he saw an elderly man approaching him, holding a sword in one hand and a rosary in the other. He was riding a four-legged creature. Was this the apocalypse, wondered German Mian. Terrified, he began to flee in his dream, but his feet moved painfully slowly. The elderly man followed him. Suddenly German Mian saw a mosque looming ahead of him. He ran inside for shelter. It was teeming with people. He couldn’t get even a toehold. Most of those present were like skeletons, dressd in tattered clothes. German Mian had not performed his wuzu, his ablutions. There was no water to be found anywhere. He was dying of thirst. He throat was parched. The water from the taps was toxic. Suddenly he saw a mound of earth behind the mosque. Running his hands over it, he attempted Tayammum, or dry ablutions. But the instant he touched the mound, three birds flew out of it. They were alien birds. Were these the Ababil birds who had stoned the soldiers on elephant-back to death? The three birds began conversing among themselves. German Mian was certain they did not belong to this world. They were shaped like distorted maps. Taking off their clothes, they began to bathe in blood, transforming gradually into humans. Humans, women. blood overflowed everywhere. German Mian had learnt outside the dream that the clothes held the beating hearts of the three bewitching women. He escaped unobserved with their clothes. After bathing, when they couldn’t find their clothes anywhere, German Mian came into view again. He said he would return their clothes on one condition. He wanted one of them to fly him to his destination. The smallest of the three birds agreed, asking, where do you want to go, huzoor? German Mian could not decide – Persia or the deserts of Arabia? He would go to Pakistan, East Pakistan. The bird chuckled. An airborne German Mian decided to join the League that very day, never mind the Maulana! He wanted to live in his dream. Considering that his dreams were being shattered every day, if he were to retain his sense of reality during this dreamlike or semi-wakeful state, the dreams would not yield to him easily. They would escape him despite being within touching distance. That night he clearly saw a beautiful, unmarried woman. She was wandering about on an uncultivated plot of land where crops had never grown. German Mian walked across this plot of land and stopped at the end of the road. Numerous other roads met at this point – these roads were so winding that they could be mistaken for snakes. He realised that dreadful battles had broken out on every street at this gigantic junction. Most of the land and people of the world were being destroyed. Only a few had survived. He was one of them. In his dream he had no idea whether his wife and child or any of his relations were alive. Night had descended on the planet. A few scattered stars were twinkling. Suddenly he discovered an elderly man approaching him, dressed in a white pirhan. His senses were alerted. He would also become a participant in this partition, a process of endless partition, which just could not be stopped. His throat was parched. He rose from his bed for a drink of water. The water hereabouts had a very bad taste. He decided to move to Pakistan.

The next morning German Mian felt rather ill. He could no longer suppress the story of his dream of the previous night. No sooner did the saga of the dream become known than there was mayhem at home. German Mian’s elder brother decided to take him to Shah Rustam’s shrine in Salar. Mejo Mian had heard his Burra Abba, his father’s grandfather, say that Khwaja Muhammad Sharif was the thirteenth descendant of Hazrat Abu Bakr, the first Caliph of Islam – his son Shah Rustam came to India from Khorasan several years ago. This extremely erudite man finally settled in Salar in Murshidabad. King Shah Alam gave him ownership of much of the land in this area. His grave was in Salar. However, instead of following in his footsteps, his son Serajuddin took the post of principal Qazi at Gaur. Sultan Ghiasuddin was very fond of him. His son Shah Azizullah busied himself with religious matters, returning to the same Salar. Mufti Muhammad Moyez was a member of this family, the bosom friend and tutor of prince Humayun Zah. Moyez sahib eventually had to serve the English. Although Khondkar Obaidul Akbar and his son Fazle Rabbi worked for the Nawab, they were learned men. But as the saying goes, Allahtaala takes away family glory after a few generations. Their progeny were now in that situation. Everyone was exploiting Shah Rustam to survive. But Rustam’s shrine was exceptionally potent. Unless German Mian was taken there, fate would always hold nightmares for him. Accordingly an awning was strung up on an ox-cart. A thick bedding was laid out on it. German Mian being a man of luxury, it was decided to take a radio along. If they left very early, they would reach Salar in four hours. A lantern was hung beneath the cart to dispel the darkness of the night. Tentuli drove the ox-cart.

As they were passing Palsha on their way to Daskamalgram, they saw a strange sight. A body lay in front of a primary school made of earth, with a thatched roof. The face wasn’t clear in the half darkness, but German Mian had no doubt it was a woman’s body. Tentuli was asked to turn the cart around. ‘No, we cannot go back,’ declared Mejo Mian. ‘Drive straight to Salar, Tentuli.’ German Mian was not accustomed to defying his elder brother. Half-sitting, half-lying under the awning, he busied himself reconstructing the face of the corpse. In his head he recited the Ayatul Kursi, the throne verse of the Quran which emphasised Allah’s power over the universe. This would make the devil flee from his presence. He also knew that, with the agony of leaving the safe haven of his home, his Al Makam Al Amin, tearing his heart apart, there was no alternative to the Ayatul Kursi to rid himself of the pain. Alongside his reconstruction of the face, he recited softly:

Allah is the immortal eternal entity who holds the entire world firmly in his grip, there is no god but him, he does not sleep, slumber cannot touch him. Everything on earth and in the sky belongs to him. No one can make a recommendation in his court without his permission. He knows all that is known to man, and all that is unknown to man is not unknown to him. What he knows lies beyond the limits of human knowledge. It is a different matter if he wishes to teach any of this to mankind. His kingdom encompasses the earth and the sky. Looking after all this does not exhaust him. In truth he is a noble entity, the finest.

Reciting the Ayatul Kursi and reconstructing the face of the dead woman, German Mian fell asleep. When you go to sleep after reading this verse, Allah sends an angel to you. The angel would guard German Mian until he woke up. Therefore there were six creatures on or near the cart now – Anwar Mian, German Mian, Tentuli, the angel, and two black oxen. Anwar Mian wondered about the woman. Who had killed her and left her here? How would she be buried? Inna Lillahe Wa Inna Elaihe Rajeoon. Surely we belong to Allah and to him we shall return.

Only the angel put all thoughts aside and accompanied the cart like a guard, sometimes perched on the awning, sometimes whirling around the lantern beneath the cart. Not even daybreak brought him relief – he would be done only when German Mian awoke. But the young angel knew that German Mian’s wakefulness was actually another kind of sleep. Just as fate never did hold dreamless sleep for him, he never left the world of sleep entirely to descend to the real world. Would the angel then have to stay with German Mian till he sank into eternal sleep? He didn’t know. He had no task other than following orders. But he quite liked the man. He visited the tall man frequently. Although his visits were professional, he had his likes and dislikes, even if he wasn’t allowed to express them. The young angel decided to sneak into German Mian’s sleep for a glimpse of the world of his dreams. The house of this man’s soul was like the Dar Ul Makama, home. Offering a mental sajdah to Allahtaala, prostrating himself in his head, he said: I proffer my sajdah to the one who has made room for us to dwell in his infinite compassion, where there is neither suffering nor fatigue.

Although the star-studded sky of Salar raised a storm of terror in his heart, he continued gazing at the beautiful form of this extraordinary world created by the Almighty.

Suddenly, a booming voice floated in from the unknown. ‘Are you afraid, Mian?’ German Mian could see no one in the sky, but when he lowered his eyes he discovered a figure in a white pirhan standing in front of him. ‘Don’t be afraid. My name is Zulfiqar Mian. I am your brother’s friend. We used to be business partners once upon a time, dealing in jaggery.’

The name was familiar. All he knew was that arrangements had been made for him to stay at the house of a friend of his brother’s. Although he was somewhat reassured on hearing Zulfiqar Mian’s name, his fear was not entirely dispelled. This was partly on account of viewing the night sky, and partly the effect of the baritone that had dropped from the above.

Still under the impact of this fear, German Mian was not able to speak, but Zulfiqar continued to converse with his guest. This man did not know how to stop talking. Khudataala had made some people in this fashion – their tongues, like galloping horses, were incapable of pausing.

‘My grandfather had told me a story, a chilling story. Not that you will be afraid – it will actually amuse you. My grandfather heard it from his grandfather. His forefathers came from Turkey. We had a traditional business of selling horses. From horses to jaggery – only the lord we worship knows what a man’s destiny holds for him. But forget about that, Janab-e- Mianbhai.’

German Mian had no idea when he had recalled all this, that he was now being told to forget it. But he said nothing. Zulfiqar Mian did not pause.

‘Do you know the name of the star you see there in the Qibla sky that points towards Mecca?’

Although German Mian could indeed see the evening star in the western sky, he did not respond. Zulfiqar Mian was not really asking him a question at all. This was how he spoke, like a schoolmaster.

‘Its name is Al Zohra.’

German Mian was reminded of his daughter. So his daughter was named after the evening star. Magnificent! He had no idea. He began to develop a fondness for Zulfiqar Mian.

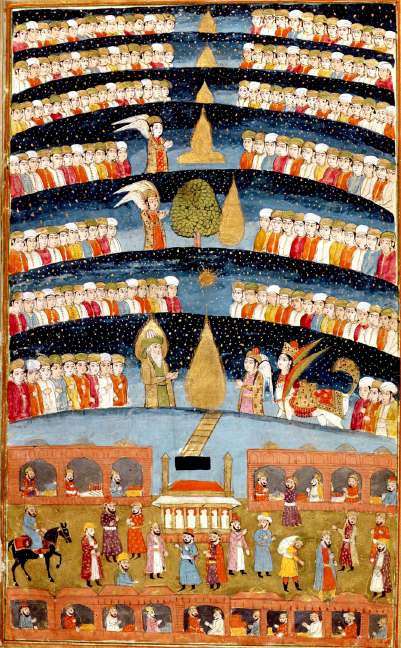

‘You will see the same star in the east at dawn. In between, a variety of twinkling stars will move across the sky all night. That beautiful sight of the heavens will make your head reel. And this is just one sky there are six more. If just one of them is so beautiful, can you imagine what the other six must be like? If you cannot sleep, lie back quietly in your bullock-cart and look at the sky – you’ll realize how powerful Allahtaala is, how much effort he has put into creating this universe.’

German Mian finally spoke ‘you were talking of a frightening story, weren’t you? Tell me the story. I will listen while gazing at the sky.’

Zulfiqar Mian smiled, and then turned grave. No smile in the world lasts very long.

He began to weave his horror story in a sombre vein.

‘A long time ago, a widow lived with her son. One day she told him, shut the door son, I’m afraid. Her son was astonished, for he did not know what fear was. When he asked his mother, she said, fear is terror. So the boy left home to look for fear. He knew that fear did not wait outside the door to be let in like a guest; it would lurk in a forest or in ocean waves. He kept walking, asking everyone he met, but no one could inform him of the whereabouts of fear. Finally he arrived close to a mountain, where there were forty dacoits, desert bandits sporting long beards and dressed like Bedouins. The very sight of them was enough to make one faint. Exhausted, the young man sat down near them. This scared the dacoits. One of them summoned enough courage to ask, where have you come from, boy? Don’t you know birds are afraid to come here, and even insects scurry away when they see us? Here are our swords, we are ruthless, come near us and we’ll slice your head off. The young man was not frightened in the least. “I am looking for fear,” he said. “Do you know where I can find it?”

‘‘Fear is wherever we are,” answered the bandit.

“Where?” asked the young man.

‘‘There in that graveyard. Go and take a look. Light a fire there and make some halwa for us – take along all you need. When you bring the halwa, I’ll answer your question.”

“The young man went off to the graveyard to make the halwa. When the aroma began to waft across the graves, an arm emerged from one of them, and a nasal voice demanded, “Give me some halwa.” Rather amused, the young man said “Of course I’ll give you some. People don’t get halwa even when they’re alive, and this corpse has such high hopes. Stretch out your arm.” As soon as the arm was extended the young man scalded it with the spatula with which he had been cooking. At once the arm disappeared. The young man took the halwa to the bandits, who were astonished. How would they frighten someone who wasn’t even afraid of the graveyard? After much discussion, they sent him off to a haunted house, which was occupied by all sorts of vicious spirits, jinns and nymphs. But these beings could not frighten him either. The dacoits sent him to all the places that people were afraid to visit, but none could scare him. Yet, his mother wasn’t someone to lie. Fear was bound to be lurking somewhere, waiting in hiding, which was why he couldn’t find it. He would not return home till he had found fear. As the young man pondered over all this in a garden, he noticed three birds. They dipped their bodies into the pond in the garden and instantly turned into houris, those enchanting virgin companions of the faithful in Paradise.’

German Hosain interrupted Zulfiqar Ali’s story. He had dreamt of three birds turning into houris, he said, but in his dream the birds had bathed not in water but in blood.

Zulfiqar Mian returned to his story, ignoring the interlude.

‘After the bath the three houris sat down to eat. Before they began sipping from their bowls, one of them extended her arm towards the young man. What arm? It was the same scalded, colourless one that had emerged from the grave, asking for halwa. The arm said, “I’ll drink your blood from this bowl today.” The young man chuckled. It seemed to him that the arm was growing longer, and had acquired a pair of eyes, a nose, teeth, two ears, and nails. The houri’s arm was dead, and yet it kept growing.’

This frightened German Mian ‘For heavens sake, stop now, Zulfiqar Bhai. I don’t want to hear this story anymore. Aren’t you going to show me the night sky? I’m very hungry.’