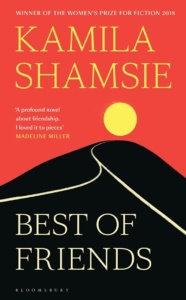

Best of Friends

Hardcover: 320 pages

|

Literary genres age, much as people do. Postcolonial literature – PoCo to friends – was once an angry young outsider leading the charge against empire. Now, much older and having made some money, PoCo seems to have compromised with the world, depicting chic, transnational lives jetting between humid capital cities and the glamorous locales of New York and London. Invariably educated at Oxbridge and the Ivy League, the characters pursue comfortable careers in politics, the media and, almost always, high finance. After a radical youth, it seems, PoCo has put away the placards and started to indulge capitalism. So say many of PoCo’s former admirers. James Wood, glossing the position of those critics, describes the contrast they see between such “smoothly global” literature and “thorny” novels full of “sharp local particularities”, asking why anyone wouldn’t read “Elena Ferrante over Kamila Shamsie”? The Pakistani-born novelist’s new book is an opportunity to examine that contention, since Best of Friends has much the same premise as Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet: a friendship charted from girlhood to middle age, taking in education, puberty, sex, ideological conflicts, personal rivalries, intimate secrets – all transcribed, however, to one of those “global” contexts. The best of friends are Zahra and Maryam, both from the cream of Karachi: Zahra the daughter of a cricket journalist, Maryam the heiress to a luxury brand. Both are enrolled at Karachi grammar school, a Victorian institution formerly attended by the likes of Benazir Bhutto, whose opposition to General Zia’s dictatorship provides the political backdrop to the girls’ coming of age in the late 80s, alongside a cultural one of Whitney Houston and Dallas. Although both girls are from the same milieu, Zahra is framed as having an “uncertain social position”. She is introspective and intellectual, compared with waggish, academically indifferent Maryam, who is destined to inherit the family fortune. Zahra makes it to Cambridge and pursues a career as the UK’s top civil liberties lawyer, while Maryam, who partly grows up in London, stays there to become a venture capitalist. The social media app she owns has a facial-tagging feature that poses a threat to the liberties for which Zahra is fighting. Nevertheless, both are nestled in the same smart set of celebrities, politicians, entrepreneurs. Zahra’s sympathy-eliciting social inferiority and her commitment to justice can be read as idealised self-presentation on the part of Shamsie, also a Karachi grammar school-educated journalist’s daughter. But the strongest hint of autobiography lies in her bookishness and sensitivity. In a lovely demonstration of both, Zahra is reading the dictionary when she informs Maryam they have a “friendship”, whereas with everyone else it was “merely propinquity – a relationship based on physical proximity”. Later in life she feels torn between “Proclivity Zahra”, who shags strangers in toilets, and “Suitable Zahra”, who courts dependable marriage prospects. Her sense of self is mediated by words and the writerly interest she takes in their semantic possibilities. All of this reveals a covert Künstlerroman – a novel about the maturing of an artistic consciousness – hiding inside what poses as yet another Bildungsroman, a coming-of age novel about “childhood crushes and first kisses” set to a soundtrack of well-worn 80s pop culture references. Those memories aren’t without charm – the girls take turns kissing a poster of George Michael – but they also form part of a subtle variation on a great and formative experience for the postcolonial writer: the confounding hegemony of western culture in far-flung places where it makes no sense. In a celebrated essay about the “alien mythology” imported to the colonies from Britain, VS Naipaul recalls learning Wordsworth’s “notorious poem about the daffodil” on a tropical island where no one ever saw one. Shamsie’s pop culture references, far from being hackneyed nostalgia, investigate this estranging experience. After watching some teen movies, Zahra muses on the inadequacy of her world: “Without detention, how could there be The Breakfast Club? Without a school prom, how could there be Pretty in Pink?” For good measure, the girls bemoan “Daffodils”, too (“Off with their sprightly heads”). Even as we are lulled into the recognisable rhythms and dynamics of a traditional English school, we are deftly reminded of the absurdity of this postcolonial situation. Alongside the school’s brass bell are distinct alarms for bombs and riots. Maryam is at one point amused to discover that the Italian for aunt is also a slang term for homosexual: the word is zia, and it hits home that all of this is taking place as Zia-ul-Haq is inventing the Taliban, and Karachi, flooded with guns, takes to “Kalashnikov culture”. These surely qualify as sharp local particularities. The latter part of the novel, where Zahra and Maryam are high-powered women in contemporary London, seems a misjudged appendage to the engrossing earlier narrative, a lapse into smooth globalism. (Shamsie wrote much more interestingly about Pakistanis in London in Home Fire, winner of the 2018 Women’s prize.) Here the novel loses its bite, I think, because the worlds depicted – big tech, judicial activism – are not ones Shamsie knows as indelibly as that of her alma mater. Towards the end, in the novel’s only formal experiment, newspaper interviews with the two women are presented. Zahra, sensitive to the unreliable narration of our selves, unpicks the lies, telling Maryam: “We all create our neat narrative arcs, don’t we?” It’s when Shamsie does that herself, crafting the vivid facts of her life into fiction, that Best of Friends is at its admirably thorniest. Tanjil Rashid | Fri 23 Sep 2022 |The Guardian

|