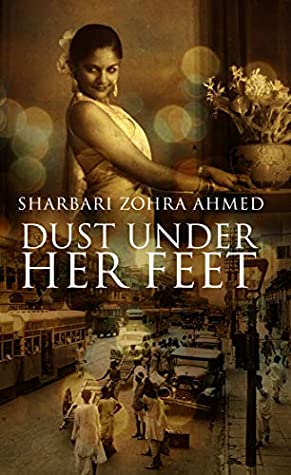

Dust Under Her Feet

Sharbari Zohra Ahmed

Paperback : 444 pages

|

Bangladeshi writing in English has seen an encouraging surge over the last couple of years. In the arena of South Asian literature, Bangladesh, the baby, is valiantly sprinting to catch up with and run shoulder to shoulder with its eminent siblings India and Pakistan, as well as Sri Lanka and Nepal. The topics, too, are as weighty and varied as the ways in which the authors are investigating them through fiction. 2018 saw the publication of Arif Anwar’s The Storm, which used the 1970 cyclone that ripped through coastal Bangladesh (at the time East Pakistan), raising a death toll of half a million, to tell a tale of intertwined lives, love, war, and history. This year, the late Numair Choudhury’s epic Babu Bangladesh! released to acclaim that has compared the novel to the works of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Salman Rushdie, and Roberto Bolano. Sharbari Zohra Ahmed’s debut novel Dust Under Her Feet adds to this promising list. It may be unusual to begin a book review by pondering its cinematic possibilities, but Dust Under Her Feet played on a screen in the darkened theater of my mind as much as its sympathetically rendered characters pulsed with blood and life from one page to the next. These are the two larger canvases on which the novel unfolded for me. I’ll return to them after I visit some of the finer points of the book. The time is the 1940s, the place Calcutta (or Kolkata in its present form), and World War II has the added impetus for India of the struggle for independence. British colonial servicemembers and American GIs fighting Hitler on one end and the Japanese on the other, are sent to the Subcontinent to hold the line in that theater of the war. The small amount of time they have for leisure, they spend at the Bombay Duck, which, as described in the back cover of the book, is “Calcutta’s answer to the wartime bars of London and Paris.” Bombay Duck’s owner Yasmine Khan is a strong, no-nonsense businesswoman, a proud Bengali and prouder Indian who is not gulled by the charms of white soldiers with sweet promises of whisking her away from her drab life, or their English pounds or American dollars. She runs her business with dignity, and in return demands nothing less from her patrons. Her club and bar are for entertainment, and the women under her care to be treated as women first, and then temporary companion, with respect as a non-negotiable part of the deal. Thus, when Radhika, one of the young women, is raped by an American soldier, and the blame is directed toward a black GI, the complexities of race, class, and privilege burst open. It is through these explorations that Ahmed turns her novel into a necessarily post-colonial space where the gaze and the lens are turned on the Anglo-European forces of exploitation, disregard, and destruction in the Subcontinent. Ahmed does this on a dual level: British colonial bigotry is held alongside American racism, neither getting anything less than the brutal scrutiny it deserves. However, as a novelist, Ahmed is completely faithful to the telling of a story, of showing characters instead of types to serve the author’s end, and of real people encountering real challenges of life in a time of conflict, upheaval, and each day bringing uncertainty of what the next day holds closer and closer. At the centre of the story is Yasmine’s love for Lt Edward Lafaver, a white American soldier with a wife back in Connecticut. As Yasmine and Edward’s relationship unfolds, so do the huge implications of giving in to their hearts’ desires. Lafaver is cut from that cloth of white American liberalism that only half shrouds its racist tendencies and has as its possible foil, the jump to accusations of racism with the righteous announcement that “some of the best soldiers in my unit are black!” This is by no means the sum of Lafaver’s character, and in Yasmine and the brilliantly drawn Patience, he and other men like him, they encounter people who have no scruples against putting them in their place (as the native is supposed to know its place in the colonial sphere). Lafaver is put on the spot when it becomes clear that Radhika’s rapist is the detestable Louis, a white officer, and Lafaver has to deal with the tenuous situation. Arrests have already been made (all of whom are black), and the word of black soldiers never holding ground against the word of a white commissioned officer (or soldier) keeps suspicion from falling on Louis. In one of the most expertly constructed scenes, the first instance of Lafaver confronting Louis plays out in a perfect balance of dialogue and action. The supporting characters of the humble and hospitable Adil Baboo, lovelorn, innocent Rahul, fiery Asha, and pliant Madhu, people the Bombay Duck in a constant stream of activity that is as urgent as the war outside their walls. The public and the private are at constant loggerheads, and the chronic tension they create is a taut but fragile string that can snap at any moment. Yasmine’s mother, Shirin Khan, is one more formidable character among a host of enduring, passionate, fiery, caring women, whose contributions to a world torn apart by men and their perfidies are consistently overlooked. Love, above all, is what they provide, which is lost in the business of war and bringing an empire to its knees. For those of us that have plied our minds and consciousnesses with literature about the Subcontinent written by Anglo-European writers, mostly men, and specifically Bangladeshi readers that have seen our own histories from Indian and Pakistani perspectives, these are heartening times. Ahmed makes her debut with a novel that speaks to the fifteen years’ effort she put into it. Her canvas is at once vast as well as skillfully contained to the story she is telling, and the world she creates, clear and alive. And going back to the novel playing in my mind’s eye like a movie, not a single page went by that I was not left wondering how a given scene would look on the screen, which actors will play which part, and how this period piece would sparkle onscreen as it pulses on the page. Nadeem Zaman | Sept 2019 | The Daily Star

|

Sharbari Zohra Ahmed

Sharbari Zohra Ahmed