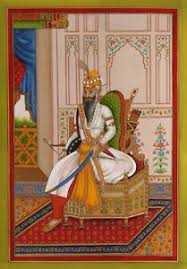

Book Excerpts: The Last Sunset: Rise and Fall of Lahore Durbar by Captain Amarinder Singh

MAHARAJA Ranjit Singh had consolidated his empire by the age of twenty one. His quest for knowledge, both to better his empire and his army, continued unabated. A contemporary of Napoleon, he was greatly interested in the happenings in Europe, the wars, military organisations, tactics, and weaponry. His inquisitiveness, verging on impatience, was geared towards improving his military arsenal and capability, and thereby his military strength and efficiency. He had the hostile Afghans on the western border and a potential threat, the British, in the east. No matter how friendly and conciliatory the British attitude was at that time, their conquest of the rest of the Indian subcontinent indicated their ultimate objective – the subjugation of his kingdom at an appropriate time.

MAHARAJA Ranjit Singh had consolidated his empire by the age of twenty one. His quest for knowledge, both to better his empire and his army, continued unabated. A contemporary of Napoleon, he was greatly interested in the happenings in Europe, the wars, military organisations, tactics, and weaponry. His inquisitiveness, verging on impatience, was geared towards improving his military arsenal and capability, and thereby his military strength and efficiency. He had the hostile Afghans on the western border and a potential threat, the British, in the east. No matter how friendly and conciliatory the British attitude was at that time, their conquest of the rest of the Indian subcontinent indicated their ultimate objective – the subjugation of his kingdom at an appropriate time.

This period coincided with the end of the Napoleonic wars and a number of European soldiers of repute, formerly of the French Army or those of their allies, looked east in order to soldier on. Persia became the destination for many as Ranjit Singh’s reputation had not reached the continent till then. Once in Persia, however, tales of Ranjit Singh and stories of his kingdom and his military prowess drew many to Lahore to offer their services to him. By the end of his reign in 1839, thirty nine European officers, including six generals, were in his service. In addition, there were three doctors.

The first reorganisation on modern lines and consolidation of the Lahore Army took place in 1822. The entire emphasis then was on cavalry and artillery. The infantry component was geared towards garrison duty. Sikhs in those days were great horsemen and as a consequence the emphasis was on the cavalry. It was only after the arrival of the European officers and Ranjit Singh being convinced of the role the infantry played in the major battles fought between Wellington and Napoleon, both during the Peninsular wars and in northern Europe, that the infantry was reorganised along the lines of the European armies. As a result, its role in battle was recognised by the Sikhs, many of whom then opted to join it.

The strength of Ranjit Singh’s army in 1821 stood at 50,000. The Fauj-e-Khas comprised 11,000 Ghorcharras divided into 15 Derahs led by eminent sardars, amongst them Sham Singh Attari, Gurmukh Singh Lamba, Hari Singh Nalwa, and two by non-Sikhs, the Mulraj Derah and the Dogra Derah`85

Ranjit Singh’s leadership and army were respected by the British, and they, therefore, preferred him as an ally, till such time that they had consolidated the rest of India. Even more importantly, they considered him a natural ally in keeping the aggressive designs of the Afghan rulers in check. As a consequence, a mission led by Charles Metcalfe (later Lord Metcalfe) visited Lahore in 1809 and a treaty of friendship was entered into. Ranjit Singh, in turn, respected British military capability and adhered to the Treaty of Amritsar for the rest of his life. He was a realist and a politically astute man and knew his strengths and shortcomings.

In his autobiography, Colonel Alexander Gardner, Ranjit Singh’s American colonel of artillery, who died in the service of the state of Kashmir at the age of ninety two in 1877, writes:

“An incident occurred during the visit of Metcalfe’s mission which brought home to Ranjit Singh’s mind a sense of the true value of discipline, and made him all the more determined to build his army on the European model. Among the Sikh troops of 1809 was a turbulent and fanatical group known as the Akalis, or Immortals, whose headlong valour had often served Ranjit Singh and turned the fortunes of a doubtful battle. The Akalis (led by Akali Phula Singh) infuriated by the sight of the religious observance of Metcalfe’s escort of Hindustani sepoys, suddenly and without the slightest warning made an attack in overwhelming numbers on the camp of the British mission, which was defended only by two companies of native infantry. Though taken by surprise, the escort quickly rallied and repelled the attack. The Akalis, in turn, incurred the wrath of Ranjit Singh more for their ignominious defeat, than for the inconvenience caused by their misconduct in making the attack”

Though Ranjit Singh appointed many generals from amongst the foreign soldiers who came to his durbar, besides the many who had been elevated to this rank from amongst those who had fought his battles for him over the years, his mind was still occupied with the question of his future command. The choice to produce future military leaders fell naturally on his sardars – be they Muslim, Sikh or Hindu – and their sons. Baron Hugel comments on a General Ram Singh: ‘He was only fourteen years’ old, notwithstanding his youth, his talents, vivacity and desire for knowledge promise great things’. However, in a general observation he also states, ‘The building completed, the Maharaja does not think the same care necessary for its preservation as for its construction, and boys, simpletons and dotards are here as in older services, creeping into command’. On the contrary, the traveller McNaughton records:

“General Officers have been selected from sons of sardars who have had their children carefully trained in the European system of military tactics. They are generally very young men, not more than seventeen years of age, and some of them whom I have seen are remarkable for their military spirit”.

Ranjit Singh had a great eye for choosing his leaders, both civil and military. It is, therefore, difficult to accept the fact that he would choose anything other than able commanders for his troops in his regular army. His successes are proof of this.

In 1836, after Ranjit Singh suffered a stroke, he appointed General Ventura, in whom he had developed implicit faith, to an appointment called ‘Chief General’. What precisely his task was is not clear, he was perhaps a chief of staff or a deputy, as in armies today. As he had been partly incapacitated due to the stroke and his health was a concern, Ranjit Singh perhaps felt it necessary to do so, in case a battle was thrust upon him while he was indisposed.

Captain Osborne records this observation of the Lahore Army:

“… the Sikh Army possesses one great advantage over our own – the ease with which it can be moved. No wheel carriage is allowed on a march, their own bazaars carry all they require; and 30,000 of their troops could be moved with more facility, and less expense and loss of time, than three Company’s regiments on this side of the Sutlej.

He goes on to give an insight into Ranjit Singh’s character as a military commander. He writes:

“He is in a most facetious humour, which rather surprised me, as reports had been received overnight from Peshawar, by no means favourable to the success of arms in that quarter. His old enemy Dost Mohammed Khan, with his Afghans, had attacked and utterly defeated a large body of the Sikh Army under one of Ranjit’s favourite general and had killed and taken prisoner upwards of 500 of them. The Maharaja seemed to bear the reverse with great equanimity, and, in an answer to some questions I ventured to put to him on the subject, said that a trifling defeat now and then was useful, as it taught both men and officers caution”.

Before Ranjit Singh, the Punjab had enjoyed international reputation in the seventh century during the reign of Harshvardhana of Thanesar due to the visit of the celebrated Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang. After 12 centuries, it once again came into the limelight under Ranjit Singh, mainly on account of the Sikh Army, which was equal to any armed force in the world at that time.

Mohanlal Kashmiri, a young man of 20, during his travels in Central Asia in 1832 happened to attend a royal durbar at Mashad in Iran, on a national festival day. The presiding prince was Abbas Mirza, father of the king of Iran. The prince asked Mohanlal whether Ranjit Singh’s court vied in magnificence with what he now saw before him, and whether the Sikh Army could compare in discipline and courage with His Highness’s Sirbaz (regular Iranian troops).

Mohanlal replied modestly but firmly that Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s durbar tents were made of Kashmir shawls and that even the floor was made of the same expensive material; and as for his army, if Sardar Hari Singh Nalwa were to cross the Indus, His Highness would soon be glad to make good his retreat to his original government of Tabriz.

Ranjit Singh created his kingdom with the help of this army. He maintained peace and order in the country and checked foreign invasions by it, but the army was not given a position superior to civil authority. The army was not allowed to interfere in administration, nor was it permitted to indulge in political brinkmanship. It did not challenge his authority at any time nor did it attempt to tyrannise the people.With this army, Ranjit Singh carved out his Punjab, as it was in 1947, from an entirely hostile environment west of the Sutlej river. A man full of foresight and intelligence. A man who used cunning, treachery and ruthlessness, along with diplomacy and the military might he created, to achieve what he did. Die all mortals must, but few leave a legacy like Ranjit Singh, creating, consolidating and ruling a vast kingdom for 42 years with these extraordinary qualities and an iron fist.