Book Excerpt – Lahore: A Sentimental Journey by Pran Nevile

The Splendours of Hira Mandi or Tibbi

Pran Nevile

Tibbi mein chal ke Jalwa-i-Parwar Digar dekh

Are ye dekhne kí cheez hai ise bar bar dekh

(Come to Tibbi to watch the splendours of the Almighty.

It’s the worthiest of sights, view it over and over again.)

Named after a nobleman fond of wine, women and song, Hira Mandi, or Tibbi in common parlance, situated in the walled city of Lahore, was in its heyday the pleasure-seeker’s paradise. It was patronised by the young and the old, the married and the unmarried, the rich and the famous, out for an evening’s entertainment in the company of singing and dancing girls. For the young and the unmarried it was an adventure into the forbidden land. Old people frequented it more for mental relaxation than for any sensual stimulation. Married men, bored with their wives and domestic life, sought to experience new delights, intellectual as well as sexual. For the rich and the famous, patronage of Hira Mandi was a status symbol which enabled them to boast of being masters of the most beautiful of courtesans. On their part, the singing and dancing girls, professional to the core, gave all their clients their money’s worth. They were at their best when trying to please the affluent among their clients, while the ordinary customers had to be content with a routine

Named after a nobleman fond of wine, women and song, Hira Mandi, or Tibbi in common parlance, situated in the walled city of Lahore, was in its heyday the pleasure-seeker’s paradise. It was patronised by the young and the old, the married and the unmarried, the rich and the famous, out for an evening’s entertainment in the company of singing and dancing girls. For the young and the unmarried it was an adventure into the forbidden land. Old people frequented it more for mental relaxation than for any sensual stimulation. Married men, bored with their wives and domestic life, sought to experience new delights, intellectual as well as sexual. For the rich and the famous, patronage of Hira Mandi was a status symbol which enabled them to boast of being masters of the most beautiful of courtesans. On their part, the singing and dancing girls, professional to the core, gave all their clients their money’s worth. They were at their best when trying to please the affluent among their clients, while the ordinary customers had to be content with a routine

performance. It was not always all song and dance, though. Greater delights were reserved

for the few who could pay for them.

It would be a mistake to take Hira Mandi for a prostitutes’street, which certainly it was not, even though some of its inmates carried on the world’s oldest profession for a living. The courtesan’s home was essentially a place of culture, particularly in Moghul times, when some of the singing and dancing girls found their way to the Royal court. There they enchanted the nobility, which sometimes included British guests, with their

accomplishments in the fine arts: music, poetry and dance. Witty conversationalists, they were engaged to teach etiquette and gentle manners to young men of aristocratic families. The elders visited them to enjoy their amorous company. With the advent of British rule and disappearance of the old nobility, much of the grandeur of Hira Mandi was lost. But, thanks to the patronage of the new princely states and the emerging landed gentry of Punjab, the pleasure-houses of Hira Mandi continued to thrive. Troupes of singing and dancing girls were engaged to perform before rajas, nawabs and rich landlords. Their presence on the occasion of a wedding was considered to be a status symbol and an auspicious sign. The art of music had been confined to these families of Hira Mandi for generations. They had produced some of the most famous singers of India.

Theatrical companies during the twenties provided some openings for the courtesans of Hira Mandi but it was the advent of cinema in the thirties that came as a real breakthrough for them to display their talents. Later, many of them grew up to be leading stars.

Broadcasting saw some others take to singing as radio artists. One of them was Umra-Zia who, with her nagma (song) ‘Mera sallam leja—Taqdeer ke jahan tak’ overnight became a singing star around 1935.

Meanwhile, Hira Mandi continued to cast its spell on the Lahorias. In the evenings, the place was transformed into one of gaiety and laughter. Soon after sunset, a row of tongas would line up outside Lohari Gate at the portals of Anarkali, where most of the restaurants and bars were located, to convey the revellers to their destinations. These four-seater shining Peshawari tongas, drawn by sturdy horses, would race towards Bhati Gate, proceeding to Hira Mandi via Ravi Road and Taksali Gate. Some of the merry-makers preferred to walk through the walled city. Passing through Lohari Gate they would go

straight to Hira Mandi after crossing Chowk Chakia, Lohari Mandi, and Said Mitha Bazar. Walking through Hira Mandi, one could see the curtained windows behind which the singing and dancing girls entertained their clients. The strains of the sarangi and the beating of the tabla could be heard from outside. One visiting a kotha is received downstairs at the entrance by the agent of the establishment and a flower-seller. He is expected to wear these stringed flowers around his wrists before proceeding upstairs.

Amidst glittering lights, he takes his seat on the carpeted floor covered with cool while sheets with bolsters to support himself. The singing girls sit in the centre with a team of musicians behind them ready with their instruments to accompany the singer. An elderly woman, acting as impressario, positions herself in a corner holding a silver plate containing betel leaves. After a brief introduction by her, the visitor settles down for an

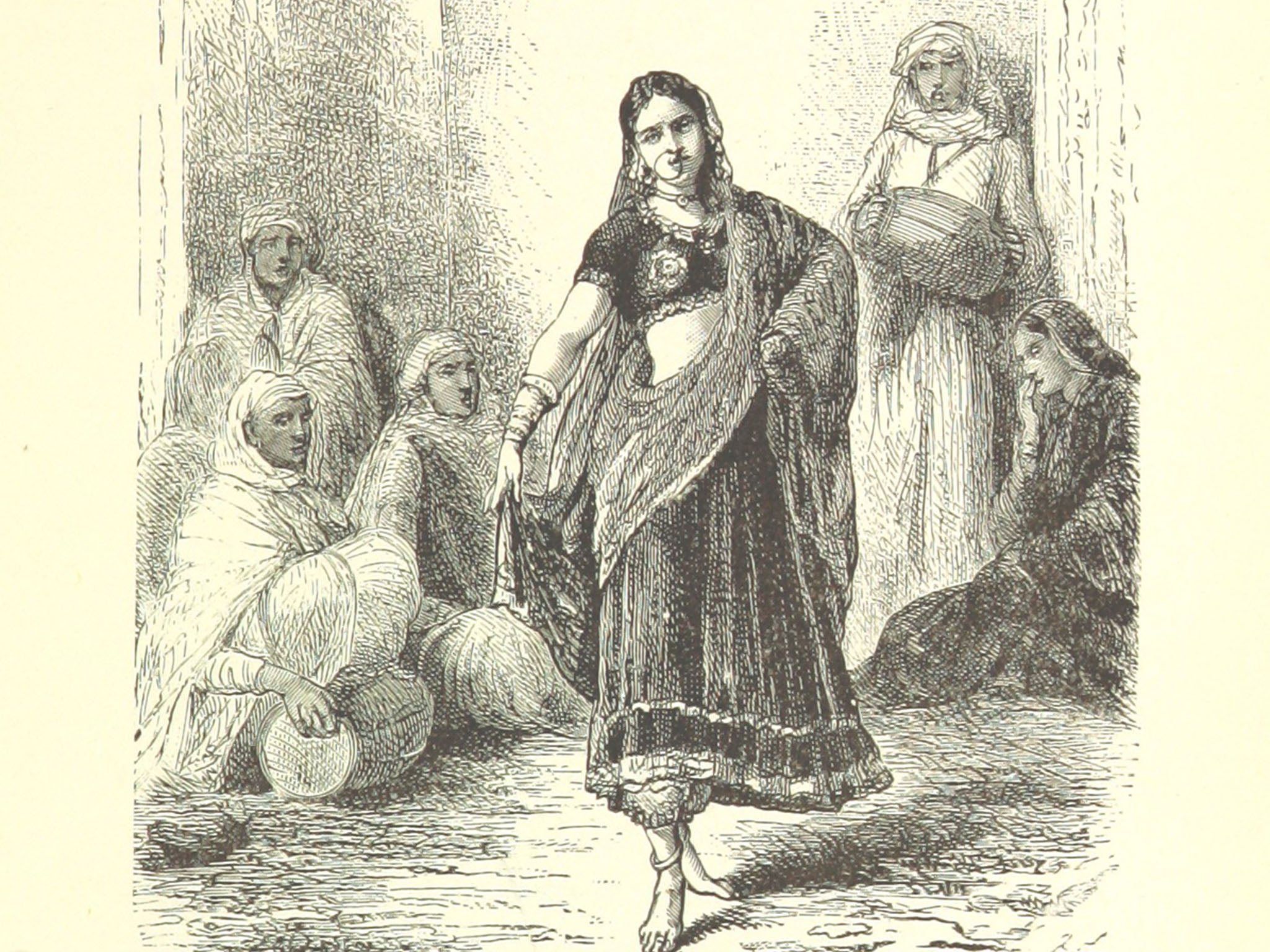

enjoyable evening. On a signal from the matron, one of the singing girls goes around offering betel leaves to the patrons who are expected to make a token present of a silver rupee coin. The singing girls are dressed in shining silk salwars and shirts embroidered

with gold or silver threads with the upper parts of their bodies covered with a fine gauze veil. They wear gold pendants, necklaces, bracelets and anklets.

Soon the stage is set for the evening’s entertainment by the musicians playing their instruments. The singer gets into her stride as she sings thumris, dadras and ghazals. She addresses each song to one or the other of the patrons who, enchanted by her sweet smiles

and languishing glances, invites her to come closer to him. He rewards her with cash which she accepts gracefully and flings it towards the matron. She responds to the requests of the patrons in turn. The cries of ‘Wa Wa’‘Bahut khub’, ‘Marhaba’, ‘Mukarar’ from the patrons encourage her to repeat the couplets with gestures to emphasise the meaning of the words. The musicians in turn get into the spirit of the song animating the whole

atmosphere. This establishes a rapport between the singer and the listener. At times, the patrons, in a hilarious mood, ask the singer to dance to the tune of the song. The sound of anklebells in unison with music and the graceful movements of her supple body, hands and feet enthral the spectators. The repeated applause encourages her to display her seductive charms. Visiting a kotha was indeed an enjoyable experience.

An event celebrated with pomp and show in Hira Mandi was the deflowering of a singing or dancing girl known as the nose-ring opening ceremony. The nose-ring, made of gold or silver, was traditionally recognised as a symbol of her virginity. Its removal signified her initiation into her new profession. The performance of the ceremony was considered an honour conferred on the wealthiest of the aspirants. The payment varied according to the charms of the girl. The ceremony was marked by festivities comparable to those of a wedding in which leading professional households of Hira Mandi and their

numerous friends and patrons took part. There were lavish feasts lasting two or three days where the choicest of dishes of meat, kababs and aromatic pulaos were served. Beggars and the poor were fed generously to seek their blessings for the initiation ceremony. For the girl, it was a momentous occasion heralding her entry into the profession. This was followed by a series of briefing sessions where the elder professionals gave her advice and

instructions on the secrets of success in her new career.

With the coming of cinema and the film industry taking roots in Lahore, Hira Mandi emerged as a centre for recruiting budding stars: actresses, singers and dancers. Many of them rose to become leading figures in later years. Some others distinguished themselves in singing and acting and attained countrywide fame. The war days in the forties saw the birth of a new class of patrons of Hira Mandi from among contractors, businessmen and merchants who were making big money. These affluent pleasure-seekers set a new trend and the Hira Mandi inmates spread out to other parts of the city to cater to their needs. This expanding clientele marked the beginning of the call-girl institution. These girls would visit hotels as well as private homes to entertain their customers. However, Hira Mandi continued to prosper. It was made even more lively by the affluent Lalas of the nearby town of Amritsar, whose spending power could not be matched by the Lahorias or even by the landed aristocracy of Punjab who had until then dominated the social scene. Some landlords hailing from West Punjab were Members of the Legislative Assembly. When in Lahore to attend its sessions, they had brought a wave of gaiety to Hira Mandi. But now the Amritsarias surpassed them. Driving to Lahore in their Fords, Chevrolets, Pontiacs, Packards, they would wine and dine at the posh restaurants, Stiffles, Elphinstone or Standard on the Mall and then proceed straight to Hira Mandi for an evening of amusement. They would patronise its blossoming beauties most bountifully, dazzling the Lahorias with their extravagance.

With the passage of time, the practice of inviting singing and dancing girls to add glamour at weddings lost its popularity. There was, however, a revival of a sort during the forties when the rich began organising private mujra parties chiefly for their male friends. I vividly remember one such gathering where the top gentry and ruling elite of Lahore were present to witness the performance of the famous singing girl, Tamancha Jan.

Sporting shimmering silks, shining jewels and gold pendants, she enthralled the audience with her lilting ghazals and provocative gestures. Encouraged by admirers and patrons, some of the Hira Mandi beauties even began visiting the racecourse and leading restaurants on the Mall, Metro in particular. The

mushrooming film studios of Lahore were always on the look-out for young female artistes. The budding directors, producers and financiers scouting for new talent found these places a happy meeting ground. Some of the girls were lucky enough to be picked up as actresses while some others ended up as mistresses of affluent pleasure-seekers.

I should like to recall some episodes, romantic as well as tragic, associated with Hira Mandi. One of them is about the murder of Shamshad Bai, a fifteen-year-old courtesan of Lahore. The accused, who was her lover, was one of the wealthiest and most influential landlords of Punjab, Nawab Mohammad Nawaz Khan of Dab Kalan. He was a perfect gentleman liked by his numerous friends among whom were Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. His hospitality was proverbial. When in Lahore, he would stay at the most expensive Flattis Hotel where he held lavish parties at which the choicest of liquors flowed freely. He spent enormous sums of money on singing girls who entertained his friends. When he entered any restaurant on the Mall, the waiters and barmen rushed to serve him. Generous to a fault, he would invite everyone who happened to be there to join him. He had studied at the Chiefs’ College where he was popular with the staff and fellow students alike. His marriage to the daughter of Mian Fazal-i-Hussain, the then Education Minister of the Punjab, a memorable event in those days, however, did not curb his high spirits. He continued to seek pleasure in women and wine. To meet his mounting expenses he sold or

mortgaged his landed estates. He travelled like a Moghul prince with his retinue of servants, singers and musicians. When he met Shamshad Bai, he was so smitten by her that he took her with him to his family palace in Jhang. It was there that the murder of Shamshad took place. It is said that Shamshad had teased Mohammad Nawaz when, in a drunken state, he wanted to make love to her. Shamshad gave him a push and he fell off the bed. She continued to laugh. In a rage he pulled out his revolver from under his pillow and shot her dead. What followed was indeed unbelievable. According to the evidence

produced during trial, the Nawab continued lying with the dead body of Shamshad for nearly ten hours.

Mohammad Nawaz was convicted for murder by the Session Court. His appeal to the High Court was pending when he died at the young age of 31, the night before Sir Douglas Young, Chief Justice, returned to Lahore from a holiday in Kashmir to hear the case. This was the tragic end of a young lovable patron who doted on Shamshad, the provocative beauty of Hira Mandi. This was a crime of passion. Our sympathies go to the singing girl unlike in the story I

am now going to narrate. Here the lover, ‘K.’ for the sake of his beloved Zohra Jan willingly reversed his role from patron to pimp. I was told this episode by a noted businessman, who ran a motor financing business those days at Lahore. ‘K.’ was a landowner of District Sargodha who had enough income from his crops to lead a comfortable life. He used to visit Lahore now and then to spend his evenings in Hira Mandi. It was in the mid-thirties that he fell under the spell of the beautiful Zohra Jan. He had known Zohra Jan for years; in fact, she grew up ‘in his hands’, as a Punjabi proverb

goes. He had been a constant patron of her family for a long time and when Zohra Jan came of age ‘K.’ was invited to perform the nose-ring opening ceremony. He was anxious to own a motor car to make a good impression on Zohra by taking her out for joy-rides.

Having never saved enough money, he had to raise a loan from a motor finance company to buy the car. He agreed to repay the loan in half-yearly instalments to coincide with his yield from the crops. The loan was to be repaid in three years but after receiving only two

instalments the finance company had no news of ‘K.’ or whereabouts. Letters and telegrams brought no response. The finance company sent their representative to Sargodha and reclaimed the car. It was learnt that ‘K.’ had gone away to Calcutta with a dancing girl from Lahore after selling his lands. He was honest enough to have left the car behind with instructions that it be handed over to the finance company when they come for it. The said

businessman forgot all about ‘K.’ until one day in the early forties when he took some of his friends to Hira Mandi to entertain them. He was accosted there by ‘K.’ who greeted him warmly and proposed that he should go up to Zohra Jan’s kotha to hear her singing.

He narrated his adventures in Calcutta where he had taken Zohra to help her enter the film line. He told him how he had lost everything in this attempt. Devoted as ever to his fairy queen, he was now helping her settle down in her old profession. Poor ‘K.’ the patron, had become the pimp.

This reminds me of a couplet I heard from an old jovial pimp about how he had landed in this profession:

Jat ke the neem julae

Us pe ban gae darzi

Lote pote ke ban gae kanjar

Ze khuda ki marzi

(From a semi-skilled weaver, I became a tailor. Then after many ups and downs, by the grace and will of God

I rose to the position of a pimp.)

I have not visited Hira Mandi for nearly five decades now though I long to go once again to that memorable haunt of the young and the old where they went in search of joy, fun and amusement.