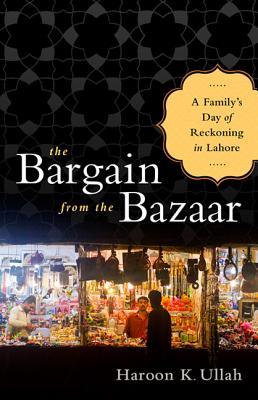

The Bargain from the Bazaar: A Family’s Day of Reckoning in Lahore

Haroon K. Ullah

Hardcover: 256 pages

|

Anyone who knows Lahore even a little will, in all probability, have visited Anarkali bazaar, the heart of the inner city where crumbling family homes lie a stone’s throw from the tight throng of shops, the tiny, tucked away mosques and the red light district.

At another stone’s throw, past the commerce and street poverty, is the sparkling jewel of the Mughal era –the Badshahi mosque, as pristine as the day it was built. This iconic, ancient bazaar is the setting for Haroon K Ullah’s book, the subtitle of which – A Family’s Day of Reckoning in Lahore – comes nearer to its subject matter than its abstruse title. Ullah tells the story of an ordinary shop-keeping family, the Rezas, whose business lies in the depths of Anarkali. The family of three sons, a working mother, Shez, and a benign father, Awais, play out the tragedy of a nation divided by its power battle between moderates and fanatics. Awais, as a soldier in the war with East Pakistan, was long ago arrested for “desertion” after heroically escaping from a prison camp. In this respect, his country has already betrayed him once. It is to betray him again when his middle son, Daniyal, falls under the deadly spell of a madrasa and its terrorist svengali. When Daniyal is suspected to be part of a terror cell, the authorities arrest Awais to lure Daniyal into their grasp. The policy here is one of “extended reach” by a government being leaned on by Washington to “get tough on terrorism”. The crimes of the son are visited upon the father most cruelly and Awais becomes the book’s poignant victim – and hero. He continues to love Daniyal, but cannot abide the hateful ideology that has led him to a “distorted interpretation of holy scripture”. Ullah clearly gained the trust of the Rezas. He has all the details, from the recreational drug-taking of the eldest son, Salman, to the romance of the youngest, Kamran. While he begins on an analytical note – “Pakistan remains a wonky, rickety nation” – with brief analysis of the effects of a “rigid concept of religion” imported to Pakistan by the Afghan Pashtuns after the Soviet invasion – he composes the bulk of the book not as reportage but as semi-dramatised storytelling. Occasionally it works – such as in those tense, re-enacted final moments of the brainwashed “martyrs” loaded down with explosives. But the book’s potency is diluted and drained by dialogue which is schmaltzy, flimsy and unconvincing. Kamran’s romance is particularly wooden. It is as if an editor advised him to shoe-horn it in – for the happy-ending to an otherwise nightmarish lesson in how powerless individuals can be when an administration that deals in bribes and chicanery comes knocking. This puzzling story of why a man from a loving, moderate family turned to terror is an important one to read, but something is lost in its telling. If only Ullah hadn’t tried so hard to tell a powerful story which would have remained so, told simply. Arifa Akbar| 21 March 2014 | The Independent

|

Haroon K. Ullah

Haroon K. Ullah