A Distant Traveller Celebrating Attia Hosain 1913-1998

Ritu Menon and Aamer Hussein

In this piece, written to coincide with the centenary of Attia Hosain’s birth, Ritu Menon and Aamer Hussein, co-editors of a new collection of Attia’s fiction drawn from early and previously unpublished archival material, celebrate her enduring influence today.

Aamer Hussein

In the margins of one of Attia’s manuscripts, I found a fragment of a poem in Urdu

In the margins of one of Attia’s manuscripts, I found a fragment of a poem in Urdu  script: ‘hamen bhi sath le chal/ai door ke musafir’ which, roughly translated, says: ‘Take me with you/o distant traveller’.

script: ‘hamen bhi sath le chal/ai door ke musafir’ which, roughly translated, says: ‘Take me with you/o distant traveller’.

Who was the traveller she was invoking? A traveller from a distance or one who traversed distances? Travelling outwards or homewards? These words became my guide as I sifted through her stories, essays, talks and travel notes. It was soon evident to me that she was the traveller and I was following, and that I had discovered a working title for the book I was co-editing.

The idea that we should put together an anthology of her uncollected work in time for the centenary of her birth had come to her daughter, Shama Habibullah, within a decade of Attia’s death. As soon as I saw the first few stories, typescripts or handwritten drafts, I knew we had a book in the making. Attia had often spoken to me about a novel she had abandoned; it was nowhere to be found. And when segments of a novel set in London surfaced from a drawer, they seemed to complete the journey Shama, I and Ritu Menon (who had come aboard at an early stage) had embarked on. The form of the book was now clear. We would, as Attia would have wanted, concentrate on her fiction. That she wanted to see some stories she had abandoned resurrected I couldn’t be sure of, but it was a risk I had to take. They were too beautiful to languish in an archive.

I had known that this would be a difficult experience, but I had to send the friend away and call in the reader/editor in me to make Ritu Menon and Aamer Hussein A Distant Traveller CELEBRATING ATTIA HOSAIN 1913-1998 1 the selection.

I had known Attia as a close family friend since I arrived in London at the age of fifteen in 1970 and knew she was a well-known writer and broadcaster; I’d read her stories and novel, which had been published when I was a child, but were still easily available then. My own long friendship with her began in 1986 when I visited to talk about her work. I had re-read Sunlight on a Broken Column. I recognised it as a unique work of fiction and lost masterpiece. In England, it seemed to have disappeared, but I had managed to get an Indian reprint. I was determined to see it back in print, along with Phoenix Fled, her short story collection, which seemed unobtainable. To my pleasure, a friend who was an editor at Virago told me that both books would be launched as Modern Classics in 1988.

The rest is legend. Attia Hosain was reborn as a writer, gained a new transnational reputation, stayed in the public eye for a decade, indeed until her eighty-fourth birthday a few days before her final illness in 1997. Her influence on two generations to follow would be and is immeasurable. Writers who were five years old at the time of the Attia revival now rediscovered Attia after her death and went off in search of her work. The pity was, there wasn’t any to be found. And so the publication of Distant Traveller is designed, in part, to fill the gap and present a range of her fiction from the beginning of her career to the very end of it (we included the last story she published in Wasafiri).

With our anthology we hope to introduce the very best of Attia’s short fiction (which she was happiest with) to those who know her through her novel; and to excite those who haven’t read it by guiding them to her magnificent books. Above all, we wanted to be sure that a hundred years after her birth and half a century after the first publication of Sunlight, new facets of Attia’s variegated talents will be gifted to old and new readers.

Ritu Menon

One knew about Attia Hosain’s Sunlight on a Broken Column (1961) almost before one

One knew about Attia Hosain’s Sunlight on a Broken Column (1961) almost before one  read T S Eliot’s poem, so indelibly had the novel become a part of growing up, and growing into, modern Indian writing. That pitch-perfect prose, redolent of a place and time steeped in nostalgia; the figure of the heroine, Laila, moving through empty-yet-filled rooms, filled with haunting memories, and that one stunning image.

read T S Eliot’s poem, so indelibly had the novel become a part of growing up, and growing into, modern Indian writing. That pitch-perfect prose, redolent of a place and time steeped in nostalgia; the figure of the heroine, Laila, moving through empty-yet-filled rooms, filled with haunting memories, and that one stunning image.

Into this vast room the coloured panes of the arched doors let in not light but shadows that moved in the mirrors on the walls and mantelpiece, that slithered under chairs … hid behind marble statues, lurked in giant porcelain vases (Hosain, Sunlight 18) – like a kaleidoscope dimmed.

Over the years, you returned to the novel again and again, finding in it a meaning you hadn’t grasped earlier, a subtext that now seems so obvious, an unusual subtlety of observation.

But then there was nothing more. No stories, no short fiction, no novels. Where did Attia Hosain go and why did she stop writing?

There weren’t too many Indian women writing and publishing in English in the 1960s which is when Sunlight first appeared, published by Chatto & Windus in London. You could count them on the fingers of one hand — Santha Rama Rau, Kamala Markandaya, Nayantara Sahgal, Attia. A little later, Anita Desai and Shashi Deshpande, but by the 1970s Attia had become a one-book writer, more or less. Her fame secure, her place in the literary firmament assured.

For us in India, she had become something of a distant presence herself by then. Living and working in London, her visits to India, though regular, remained family-and-friends oriented or limited socially to the literary circles of Bombay and Lucknow. All the years that I was working as an editor in various publishing houses in Delhi in the ’70s, she was a tantalising absence. In London, however, she was more than actively involved with radio and television and on the stage. And then, in the 1980s, she made a remarkable comeback with the reissue of both Sunlight and Phoenix Fled by Virago, in 1988. Her earliest writing, Attia Hosain has said, was in her diary, begun when she was just fifteen, a diary not of events but of emotions: ‘I suppose that is the inevitable form of the diaries of young introverts without much self-confidence’ (Undated talk np). She developed what she called an ‘irritating habit’ of blanking out in the middle of a conversation, staring into space – or looking inwards, perhaps? – even as the person with her continued talking. ‘Where are you?’ they would complain, ‘I was talking to you.’ Where she was, was busy transcribing the conversation mentally, ‘writing it within inverted commas’, using it later as a study or as a starting point for ‘other pieces of dialogue in a book I was forever writing in my mind’ (ibid).

Unlike the normal run of adolescent diary writers however, Attia’s diaries, journals and notes ran to over 1,000 pages and continued well into the 1990s.

Attia arrived in London with her husband and two young children in 1947. The partition of India and the compulsion to choose a country and nationality resulted in Attia’s first assertion of identity — her refusal to be slotted into ascribed categories that she repudiated (Indian. Pakistani. Asian Immigrant.). She opted, as a citizen of the Commonwealth and holder of a British passport, to remain in England, and all of her published stories and the novel were written while she lived there.

After her husband left the UK, Attia not only found herself alone in London but, for the first time in her life, absolutely on her own. She decided then to do something she had wanted to for many years — concentrate on writing:

There was so much one wanted to express but could not. I cannot describe to you how tormenting a feeling that is. There was also a persisting lack of self-confidence, and a feeling of inadequacy. It used to come over me each time I read a good book; it overwhelmed me in a library or a bookshop. (ibid)

The first story she wrote in England, called ‘Lilliput’, was published by a well-known English magazine, followed by a second which appeared in the American journal Atlantic Monthly. These early successes were of course encouraging, but she was plagued by a persistent lack of confidence and a feeling of inadequacy. What could she possibly have to say that had not been said already, far better than she could ever say it?

But that ‘need to write’, of being driven to it, could not be suppressed, in spite of herself and what she called her circumstances. ‘It is like carrying a germ in the blood,’ she wrote, ‘and every now and again must cause an eruption’ (ibid). Still, one might speculate that it was these very circumstances, a combination of dislocation and political choice, that resulted in her fiction; one might further speculate whether, if she had returned to live in India, she would have written, or written differently. That ‘germ’ in her blood might, in other circumstances, have remained suppressed, for the whole structure of society would have been its accomplice: It encouraged one to sink into the easy anonymity of its pattern for womanhood. All it asked one to be was a wife and a mother, and to be both or either involves a scattering of one’s personality. To write with integrity the mind must be integrated. (ibid)

Friends in England had to lock her in a room to make her write and she would routinely destroy a great deal of what she wrote. When Chatto & Windus accepted her first anthology, Phoenix Fled, in 1953, she was gratified that she had been published, not because the content was Indian or that she was a woman, but because the stories were good. Eight years later, in 1961, they published Sunlight, with Cecil Day Lewis as her editor for both books.

More than fifty years later, walking down a leafy London street with the writer and literary critic, Aamer Hussein, he mentioned casually that 2013 would be Attia Hosain’s centenary year and that her children were thinking of putting together a miscellany to commemorate the occasion. Would I be interested in publishing it, he asked. I responded with cautious interest, wondering what such an offering would contain. A selection from Phoenix? Excerpts from Sunlight? From some of her essays, perhaps? Wouldn’t it be too much of a mixed bag? There may be some new material, Aamer replied (also somewhat cautiously), so of course I perked up. Not enough by itself for an anthology, but something old, something new, might be just the thing for a centenary? There are some unpublished stories, he continued, maybe even chapters from a new novel …

So, she hadn’t destroyed everything … And, yes, I was more than willing to see what we could do with this, a slow excitement building up in me at the thought of a ‘new’ Attia book. We agreed that Aamer would make a preliminary selection from Phoenix, which her daughter, Shama Habibullah, and I would concur with or modify, as far as previously published stories were concerned; and then we would together read the new material and agree on a final selection.

It would be true to say that I had no idea what to expect from the latter.

Shama sent xeroxes of the unpublished stories to Aamer in London who sent them to me in Delhi; I photocopied them and sent one set back to him so that we all now had copies of the manuscripts to refer to in our inter-city, international communication — but it also made for some interesting problems as we went along! It’s been a long time since I read a typewritten script and that too, obviously tapped out on a manual typewriter! On foolscap sheets, some clear, some where the ribbon was clearly a bit worn and the copy smudged; with xeroxing the impression was even less clear, though still legible. And at least three stories were only handwritten. There was no way to tell whether these archival pieces were first drafts, revised texts, works-in-progress or finished pieces — except by conjecture. If they hadn’t been published, was it because they were incomplete or still being worked on? Was this because Attia herself had rejected them or simply forgotten about them? Would she, meticulous craftswoman that she was, have wanted them published at all in this (possibly inchoate) form? Could we take her handwritten amendments or crossings-out as final, tentative or … ? And then, the BIG question — when exactly had they been written? The chapters from the unfinished novel were only in handwritten form, on unlined foolscap, one¬-sided sometimes; at others, partly continued on the reverse or with notes and additions in the margins, trailing across the top of the page or carried over on the back. How impossible it is, in these days of effortlessly erasing, transposing, rewriting and deleting on a computer, to see the actual process at work, the half-formed, tentative thought before it becomes fixed on the page, assured and unchanging.

Early on in our discussions we agreed that this would be a fiction anthology rather than a miscellany; and, except for the inclusion of ‘Deep Roots’, her most recently published essay of 2000, there would be no non-fiction in it. And so in January 2010 we began keying in the unpublished material, stories and novel chapters, while simultaneously making a selection from Phoenix.

Attia Hosain’s earliest stories were published while still in her teens, as a university student; of the six or seven unpublished ones that we were considering, Shama and Aamer conjectured that at least four, if not five, had been written as early as the 1930s; only one, ‘The Old Man’, possibly in the 1960s. ‘Storm’, ‘The Healer’, ‘Leader of Women’, ‘Coolie’ and, probably, ‘Journey to no End’ as well were apparently her made-in-India stories, most likely written while still a student or shortly thereafter. This was something of a revelation, at least for me, for the texture and sophistication of the stories were remarkable; and in ‘Storm’, ‘The Old Man’, ‘Healer’ and ‘Journey to no End’ there is a sensibility and critical insight so astute as to even 6 eclipse some of her later published stories. They came to her ‘almost complete’, she has said. The title story in Phoenix Fled, for example, came to her as she was walking home from work one day, beginning with an image that had stayed with her. Her grandmother had told her a story about another grandmother during the Great Indian Revolt of 1857:

When the British soldiers came to village, all the people hid in underground rooms, but one woman went up to her roof and shouted at the soldiers not to trample on her flowers. That was what I built the story on. Old Granny in this story refuses to leave when everyone else runs away during the Partition […] . (in Bharucha 20)

It was like Ismat Chughtai’s old woman in ‘Roots’ who hides in the coal scuttle of her house, refusing to accompany her children to Pakistan. Our respective concerns during the keying in and correcting, however, were somewhat different. Should we, in each instance, respect a change she had made if, in our assessment, her earlier expression or construction was better? Should we – could we? – restore crossed-out paras or sentences if they amplified the character or situation or otherwise enhanced the story? This occurred most often with ‘The Healer’ – a story of powerful brevity and poignance – which had heavily crossed-out sentences and overwritten text. One particular sentence – or should I say, sentiment – I wish we had retained went like this:

So old was she in her mind, so young in her years, and I saw the pity of it, the pain her sensitiveness would always bring her. All the energy seemed to be diverted from her body to her mind.

This now appears as:

So old was she in her mind, so young in her years, and I saw the pity of it. She who had shunned all contact with people now sacrificed her sensibility to her ambition.

‘The Leader of Women’, for example, was incomplete, yet we decided to include it together with the author’s note to herself: ‘Unfinished — because I don’t know what I was driving at, really. What can I do to this?’ It is her one unequivocally ‘political’ story, the leader modelled on Sarojini Naidu, exposing the hypocrisy and doublespeak of the political class when it came to women in public life. The story in which her rephrasing altered at one stroke the tenor of her telling is ‘Storm’, in its very opening sentence, which changed from ‘After dinner the ladies left the men in the dining room’ to ‘After dinner the ladies retired in order of their husbands’ civil list precedence in the dining room’. There is not one superfluous word or thought, but a whole social protocol is established at the outset. ‘Only maturity can balance sensitivity,’ Attia has said, ‘because one wishes to savour the essence of experience, enter into it completely in the search for the reality behind appearances, each experience becomes more than life-size’ (Undated talk np).

The 1930s stories are notable for their lack of exoticism and for the clear-sightedness with which they observe the flux and tensions of a society transiting from feudal to democratic, traditional to modern. In an unexpected, perhaps curiously unintended way they are a counterpoint to the aristocratic, noblesse-oblige Lucknow canvas of her later published fiction.

‘When I was growing up, politics and literature were the two topics which were discussed at home,’ Attia said in a 1997 interview (in Bharucha 20). Lucknow in the 1930s, like much of north India, was seething with political ferment and families like hers were in the thick of it. Nationalist Muslims, together with the progressives – among whom were prominent leftleaning writers and intellectuals – were frequent visitors in her natal home; her in-laws, on the other hand, were Muslim Leaguers. Comrades on the run sometimes took refuge in her father’s house and Attia herself, though never drawn formally into the Progressive Writers’ Movement, was nevertheless influenced by it. She was possibly the only woman writing in English in the 1930s to focus on the underclass outside the feudal household. ‘Coolie’ and ‘The Old Man’ could quite easily be read as belonging to the progressive canon were they not distinguished by her singular sensibility and style.

A more full-blown political expression was also part of her original draft of Sunlight. ‘There were many political sections to this book which Cecil Day Lewis persuaded me to leave out,’ she said in the same interview, ‘saying it is the human interest which is important and not politics. I tore up those papers. I wish I’d kept them’ (ibid). (Nayantara Sahgal encountered the same response from her editor at Knopf to the political sections in the second volume of her autobiography, From Fear Set Free, published in the same year as Sunlight. She, too, regretted having dropped them from her revised, published text.)

What stays with us from Sunlight is a kind of Proustian remembrance, an elegy for a time and place sundered by a politics so divisive and irrevocable, so overwhelming yet still unresolved and unreconciled. Laila, the heroine, bears witness, her story is testimony to the futility of violence and the novel remains one of the most political written at the time. This is one important reason why it endures.

On writing, Attia Hosain has said:

You must keep trying because it is as essential as drawing breath — like exhaling! All the thoughts breathed out and shaping themselves visibly after being inside the cells of the brain, and then released. If you hold your breath and do not breathe out, you will suffocate. (Notebook, 1980 np)

Sunlight was Attia’s last published work but she continued to write voluminously, filling her journals and notebooks with accounts of her travels, reflections on literature and life, personal circumstances and family affairs, events in politics and society around her — and a new novel. It remained incomplete, but the chapters Shama found, as well as the notes to herself that Attia made regarding characters, relationships, plot development and location indicate a work of astonishing power and depth.

It is set in London of the 1970s (1972 to be precise) and would have been her only fiction located outside India. The characters are diasporic South Asians (as they are now classified), Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis making their way in a country and at a time that was tense with a reactionary politics. Enoch Powell, conservative MP, had threatened that ‘rivers of blood’ would flow if there were not an immediate and drastic curb on immigration. Murad, the protagonist, has decided to return to India, to Lucknow, feeling ‘stifled by the alien pressures’ of this new environment. That very environment which had stimulated him when he first arrived, breathing the air of freedom, is now oppressive; life in this society it seems to him, is conducted in ‘an aspic of aloofness’:

He lived among people as elusive as mist, as cold as fog, as warm as sun shining through it, kind and helpful as if they doctored him patiently, wearing gloves and masks, settling him comfortably in a glass-barriered special ward. But he would keep on breaking out and reaching out for the solidity, the warmth, the inescapable reality of human relationships. He had expressed this need in many small and often to himself, laughable ways. (Hosain No New Lands, 61)

He has just been to offer his condolences over the sudden and tragic death of his friend, Isa, killed in a drunken brawl; as he walks the streets after his meeting with Isa’s (Pakistani) widow, he is assailed by memories of his friend who, when the country was divided, became Pakistani. Neither Murad nor he is at ease with their new nationality, nor yet in their newly-adopted country:

‘There was a time, my friend, when there was no gap between appearance and reality to be filled in with explanations. No one asked “Are you Indian?” just as no one said “Are you alive?” And I? Living or partly living. Drink to partly living.’ They drank.

‘But, my friend,’ said Murad, in a drowsy haze of intoxication. ‘The time did come for questions. You and I together did need explanations. Indian? Yes. Pakistani? Yes. Both Muslims. Yes. Yet different? Yes. How? Why not? Appearance the same. Reality? Different. Let us drink to the different sameness.’

‘Let us drink.’

‘To Pakistan, where you went.’

‘To India, where you will return.’

‘To the Siamese twins.’ ‘To their midwife.’

‘Rule Britannia!’

They were both floating now towards a lachrymose melancholy.

‘I swore loyalty to the Queen and country, I a citizen of the UK and Colonies. Mark the words, Murad. What does the word loyalty mean? You who have a country, tell me. Do you swear loyalty to a patch of earth or what it stands for? To an abstraction or ideals? I brandished banners against Colonialism. My father was beaten and imprisoned for his country’s freedom from the country I have sworn loyalty to. We were poor, and my mother suffered when my father took to going in and out of jail. You wouldn’t know what it was like, with your people comfortably bargaining for equality in drawing-rooms with English guests over a glass of whisky.’

‘I resent that. It’s bloody nonsense. Partly class jealousy. My family weren’t toadies.’

‘Come now, my brother, my friend. We have been made to fight enough. Let us drink to freedom.’ They drank to freedom with tears in their eyes. (No New Lands 51-52)

The novel breaks off at the point that Murad enters The Pride of Asia, a restaurant owned by Chaudhary, a Bangladeshi who, in the naming and re-naming of his restaurant, encapsulates the troubled recent history of the subcontinent. It is clear from the two chapters that Isa’s widow will reappear, as will the half dozen characters already present in this beginning, for they are delineated in the author’s notes and some relationships hinted at. If there is one thing that leaps off the pages of her unfinished novel it is the refusal of her characters to be stereotyped — Isa’s widow is a stunning example. Speaking for herself, Attia declared:

I object strongly to being slotted into little niches on the basis of my ‘ethnicity’. I find such categorisation racist — I am not an ‘ethnic minority’. I am a human being and should be treated as such. (In Bharucha 21)

The novel had no name; the title we gave it – No New Lands, No New Seas – is taken from a poem, ‘The City’, by the Greek poet C P Cavafy, exiled in Alexandria. It held particular significance for Attia, who found in its haunting evocation of loss and unfulfillment an echo of her own deep sense of out-of-placeness. Here she was in a country she had chosen to live in, a country that had given her so much.

But I cannot get out of my blood the fact that I had the blood of my ancestors for 800 years in another country. It is this that drove me to write. Maybe it was because as a stranger here it was easier to collect one’s scattered bits together in one piece. Maybe it is that with the years one’s sense of values becomes clearer and there is an end to wandering away from the things which give real satisfaction. (Undated talk np)

Attia Hosain

Attia Hosain

Attia Hosain was born into a wealthy landowning family in northern India. Her father was educated at Cambridge University, and her mother was the founder of an institute for women’s education and welfare. Hosain attended the Isabella Thoburn College at the University of Lucknow, becoming the first woman from a landowning family to graduate in 1933.

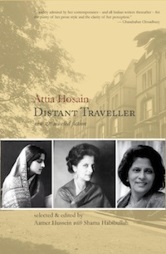

Distant Traveller: New & Selected Fiction

Distant Traveller: New & Selected Fiction

Attia Hosain

This book is a fitting tribute to an important but all but forgotten woman IndoAnglian fiction writer who sensitively chronicled the complexity of life in the times of the British Raj and the early years of Indian Independence in the novel, Sunlight on a Broken Column.

Sunlight on a Broken Column

Sunlight on a Broken Column

Attia Hosain

The majority of Anglophone fiction in India in the 1950s and 1960s was based on the questions of nation and history. The Indian English writers were preoccupied with either partition narratives or national allegories.

Phoenix Fled

Phoenix Fled

Attia Hosain

In 1953, Attia Hosain published her first book ‘Phoenix Fled’, a collection of short stories, with Chatto and Windus. In 1988, ‘Phoenix Fled’ was re-issued by Virago with an introduction by writer Anita Desai. The introduction and the first story, “The First Party”, have been