Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America

Vivek Bald

|

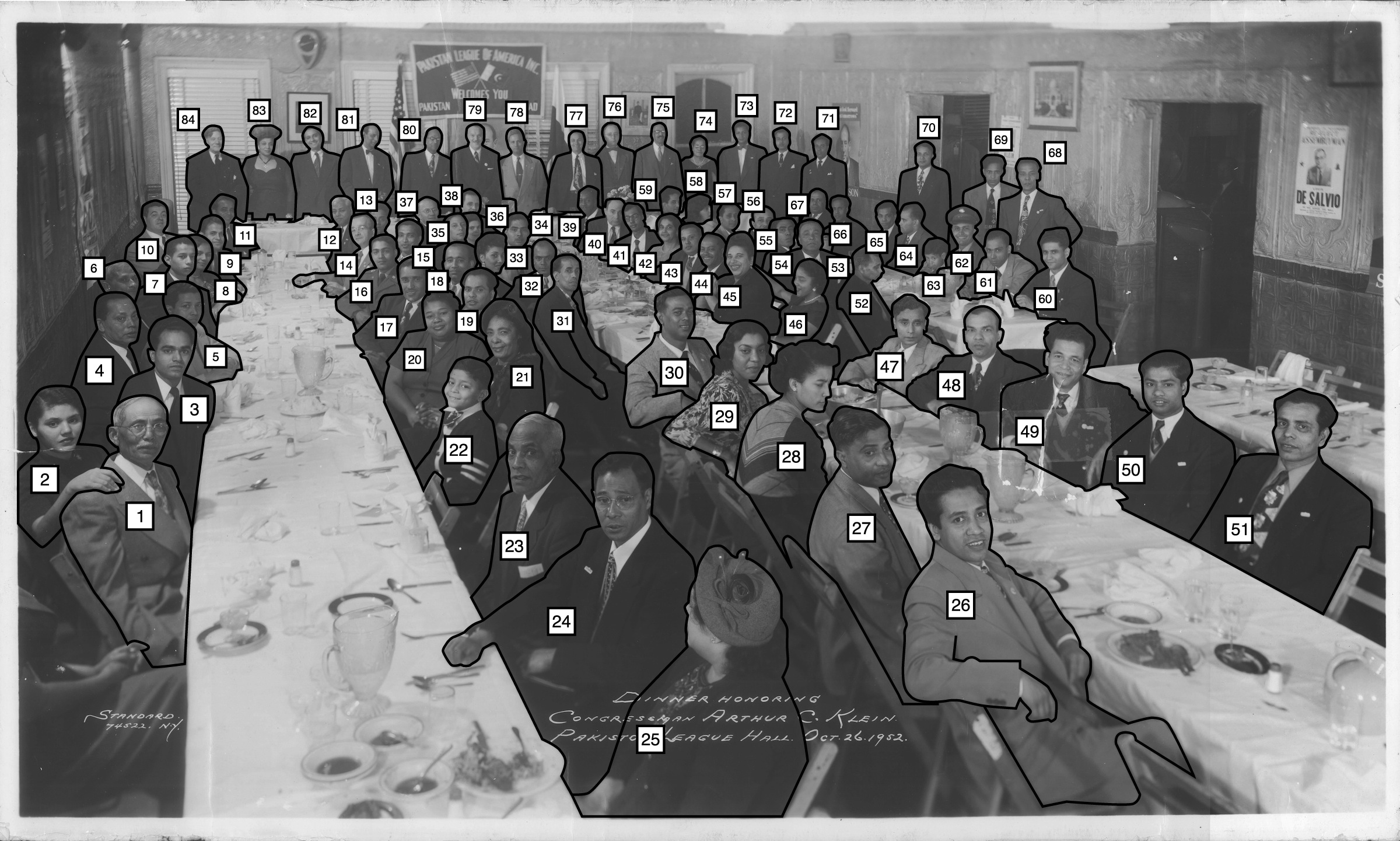

Vivek Bald’s Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America is a highly detailed and beautifully written account of the lives of South Asian immigrants who arrived in the United States between the 1890s and 1940s. In piecing together the stories of this early immigrant group, Bald draws on census records, marriage licenses, ships’ logs, personal memoirs, newspaper clippings, and interviews with the migrants’ spouses and descendents. Bald, who is a documentary filmmaker, scholar, and assistant professor at MIT, will also present the stories in an upcoming documentary entitled “In Search of Bengali Harlem.” The lives and trajectories of the men Bald discusses have long remained unaccounted for in both popular and scholarly sources on South Asian immigration to the U.S. Attention tends to focus on subsequent waves of white-collar professionals, who arrived following the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. Prior to 1965, South Asian migrants in America were met with suspicion and unease and their presence eventually criminalized. The 1917 Immigration Act designated East Indians as “undesirable aliens” to be turned away at the border. In a similar vein, in the 1923 case U.S. v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the Supreme Court ruled that even those East Indians already resident in the U.S. were racially ineligible for citizenship, because they were not “white.” Due to the climate of hostility and xenophobia, undoubtedly compounded by state-sponsored exclusion, many erroneously assume that South Asian immigration to the U.S. came to a halt during this period. In fact, Bald’s work reveals that throughout these years there was a small but continuous flow of migrants from the subcontinent, many of them working class Bengali Muslims from the regions that today comprise Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. The chikondars and the lascars In the book, the men are broadly divided into two categories. The first were groups of Muslim peddlers who journeyed from their villages in the area of Hoogly, West Bengal to holiday destinations such as the boardwalks of New Jersey, laden with bags of embroidered silks to meet American consumers’ demand for luxury goods from the exotic “Orient.” Their journeys began in the 1890s and stretched into the twentieth century. Known as chikondars (after the style of embroidery on their products, chikan), these men became a fixture at American leisure spots on the eastern coast. Many also traveled to cities like New Orleans, in the then-segregated South. Most chikondars did not stay permanently the U.S., remaining instead “soujourning itinerant peddlers.” Interestingly, Bald makes clear that these men’s transnational lives were made possible by women –both those back home in the villages of British India (who produced the goods they sold) and by African-American women in American communities of color, who welcomed members of the trading network. Though global in scope, these vast networks became firmly embedded in American neighborhoods of color, such as Tremé in New Orleans. Of the men who did choose to settle in the U.S. permanently, many married local African American women and raised families – dwelling in the margins of the U.S. immigration regime and challenging the rigid racial classifications of the Jim Crow South. Two decades later, a second group of South Asian men began arriving in the port cities of the Eastern seaboard. They were Indian sailors of the British merchant marine, known as lascars, who originated primarily from villages in the Syhlet, Noakhali, and Chittagong areas of present-day Bangladesh. Harsh conditions and abuse aboard British vessels made cities like Baltimore and New York all the more attractive, leading hundreds of seamen to jump ship. They melted into the urban landscapes, aided by networks of support that included “kin, fellow workers, and local residents” (p. 117). Many went on to find work in factories in places like Detroit and Chester, PA, or to become entrepreneurs, responsible for some of the first Indian restaurants in New York. The Role of American Communities of Color Around this time, Harlem became well-known as “the epicenter of the African American world” (p. 162), and the neighborhood attracted large numbers of migrants during the period of Great Migration from the American South. As Bald’s painstaking research reveals, however, Harlem was not just a destination for southerners, but for immigrants from across the black diasporic world, such as the English- and Spanish- speaking Carribbean. By the 1930s, a number of Indian Muslim ex-seamen had also married into Harlem’s communities of color and lived there with their Puerto Rican, African American, or West Indian wives. The sheer volume of information Bengali Harlem presents is striking, and the rich history explored in its pages fascinating. It is also important to consider the significance of this history in terms of common conception of neighborhoods like Tremé, Harlem, and Black Bottom, Detroit as exclusively African American. Bald reveals that these neighborhoods were not only built by southern migrants “familiar with the worst the worst aspects of racial power in the U.S.” but also “by immigrants of color from other parts of the world who had experienced life under colonial rule” (p. 226). Such neighborhoods were intermixed and “multicultural” before the word was widely used – a mélange of cultures, religions and languages. Importantly, these spaces were the only ones that offered South Asian Muslim migrants the possibility to build a life in a largely hostile U.S. – at a time when their home villages were still chafing under British colonial rule. As Bald puts it:

Personal Stories and Political Possibilities Importantly, Bengali Harlem not only evokes the hybrid cultural landscape of a bygone era, but reminds us that personal and political solidarities beyond the narrow scope of ethnicity or religion are possible. This is evidenced on a personal level in the marriages and friendships between the Bengali migrants and other local residents – be they Puerto Rican, African American, Italian, or West Indian. Beyond that, Bengali Harlem illuminates the struggles that united African American, Caribbean, and Indian activists, who were “emboldened by a sense of common struggle against the injustices of racialized power both within the United States and across the colonized world” (p. 225). This comes across most clearly in a chapter on the life of Dada Aimer Haider Khan, a Kashmiri Communist and anti-colonial agitator, who fled the British Raj and experienced an “awakening” among politically engaged African Americans in Black Bottom, Detroit. Thus, while Bengali Harlem offers an exquisite glimpse into the past, it holds significance that moves beyond the historical. The recovered histories of Bengali Harlem are not merely the personal narratives of an early immigrant group. They alse serve as a record of the political solidarities and spirit of internationalism within American neighborhoods of color in the early twentieth century. As Bald notes, these spaces were home to contestations and struggles – but also to community, solidarity, and inclusion. Neighborhoods like Black Bottom, Detroit, have since been bulldozed, but Bengali Harlem reminds us of the political solidarities that once existed there, and of those that remain possible today. After all, we look to history in part because of what it tells us of possible futures. When histories are lost, it not only narrows our conception of the present, but limits our imagination of the worlds that could be. Calynn Dowler | 12 Sept 2013| The Migrationist

|

Paperback: 320 pages

Paperback: 320 pages