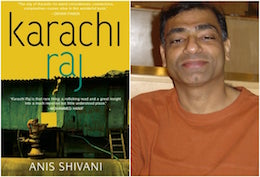

Anis Shivani’s homage to Karachi

Karachi Raj is critic and poet Anis Shivani’s homage to the city where he was born and spent his childhood. While the story follows three main characters, Seema, Hafiz and Claire, as they negotiate the city’s hierarchies and complexities, it is also a story about the denizens that bring Karachi alive. At the heart of the novel is the metropolis itself: resilient, unpredictable and generous.

Karachi Raj is critic and poet Anis Shivani’s homage to the city where he was born and spent his childhood. While the story follows three main characters, Seema, Hafiz and Claire, as they negotiate the city’s hierarchies and complexities, it is also a story about the denizens that bring Karachi alive. At the heart of the novel is the metropolis itself: resilient, unpredictable and generous.

Belonging to a Pakistani Memon family, Shivani is a graduate of Harvard where he majored in economics and the social sciences. Shivani was working as an economics researcher in Cambridge, Massachusetts, when he decided to move to Houston to “escape that East Coast bubble of sheltered opinions and sheltered lives” and take “refuge in what felt like the least literary place in the world, Houston, Texas of the 1990s”.

Over the past two decades, Shivani has written and published anthologies of poems and short stories (The Fifth Lash and Other Stories; Anatolia and Other Stories; My Tranquil War and Other Poems) but Karachi Raj is his first novel. Shivani admits that he is, like most authors, a hermitic writer and that the one thing that he is passionately opposed to writing on is what has become a cliché for most fiction authors of Pakistani origin – the post 9/11 world and terrorism.

In a lengthy interview with Images, he talks about the challenges of publishing Karachi Raj and what he loves most about the city that he once called home.

1. Karachi Raj encapsulates the different personas of the metropolis: the reader is taken from Regal Chowk to the heart of the film industry, from the Basti to the inner workings of KU. Characters from all walks of life populate the novel: NGO-wallahs, philanthropists, socialites, the Pakistani president, a feisty rickshaw-wallah, construction workers, shopkeepers, a housewife, an anthropologist… but in many ways the central character is the city itself. How did you go about writing this novel? And what was the inspiration behind it?

As someone born in Karachi, who harbors intimate knowledge of the city, I felt it had not yet received its due in fiction. The original title of the novel wasThe Slums of Karachi, but the novel is about much more than slums. It seeks to capture the different classes in their interactions with each other, and to penetrate the smokescreens of obfuscation the middle and upper classes in Pakistan throw up around themselves.

What is the unique nature of Karachi’s optimism and energy? Where does Karachi succeed in fulfilling its citizens’ dreams for a better life and where does it fail? What is the hierarchy of values and how does it get translated into distribution of resources and rewards? What is special about Karachi’s history — for example as the locus of much of the migration that occurred after Partition — and how does this illuminate the trajectory of other cities in comparable situations? This is what I was after in depicting the various physical manifestations of the city.

When you encounter Regal Chowk or Karachi University, or Tariq Road or Bunder Road, you’re experiencing layers of history contesting with each other, history being lived out concretely in the experiences of citizens, not history as abstract unreality. For example, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto wreaked certain transformations on Karachi, as did Ziaul Haq, and these innovations shape the body politic to this day, manifested in permanent physical overlays.

Going to the beach today — for example when the anthropologist Claire visits Clifton with her photographer-guide Tipu [in the book] — is a different experience than it was in the 1940s and 1950s, or the 1960s and 1970s. Likewise for attending the university, or buying a book, or dealing with domestic help, or eating on the streets or in restaurants. A city like Karachi has meaning to the degree that it is malleable, having the ability to take on the mood and coloring of the people.

Hafiz and Seema, and their family in the Basti, were the germ of the novel, and over many drafts and revisions their personalities remained essentially the same. Along the line I picked up Claire as an integral part of the story, her anthropologist’s point of view allowing me to structure the novel in an ironic yet empathetic manner. The three different streams of narrative overlap but are sufficient unto themselves, so it’s like having three distinct novels of Karachi within the space of one.

When at last I hit on the humorous yet reflective tone after many tries, I was able to bring in, quite smoothly, a vast array of characters who each appear on the stage and do their business with the least amount of fuss while leaving a lasting impression. Having the physical presence of the city as the central element allowed me to include and exclude characters at will while retaining a tight focus.

The city absorbs everyone within the amorphous whole yet everyone remains distinct. The roving eye pokes into and illuminates hidden corners, not necessarily dark secretive ones but also joyous colorful ones. There is so much movement and energy in Karachi Raj, and I was able to tap into that because I had no points to score, no bias besides being true to the reality of the characters.

2. Karachi Raj is not the typical Pakistani English novel; it’s not about terrorism or politics or overt violence, many of the characters are simply negotiating or making sense of the patriarchal system they are living in…

Yes, I was absolutely not interested in making terrorism or political ideology or violence my focus. This has been overdone and exaggerated, and feeds into the myth of self-destructive violence that publishers in the West are eager to propagate.

Frankly, I am sick and tired of such novels. Does the world need another novel about an unfortunate who is torn between religion and secularism, occurring in the background of the war on terror, the omnipresence of spies and the military?

We certainly don’t need it if it is packaged in a narrative that comforts Western readers, namely that Pakistanis — and other Third World people —are the sole instigators of their own misery, poor befuddled folks who can’t tell what’s good for themselves. If you want to tell the truth about these things in fiction, you would have to do so in a manner, implicating imperialism, which would be unacceptable to Western publishers.

You’re right that the characters in Karachi Raj are simply negotiating the terrain of daily existence, not just in terms of the patriarchy but also other systems of domination including the economic and religious ones, whether it’s Seema trying to work out the bounds of acceptable romantic expression, or Hafiz figuring out the different roles he is expected to play in his encounters with different social classes. It is in representing the daily business of living in stark detail without melodrama or sentimentalism thatKarachi Raj seeks to make its impression.

The detail, if it is written with skill, takes on an inherent drama of its own that far exceeds false manipulations of plot, in the form of sensational political occurrences, for instance. There is tremendous drama in how a poor young man from the Basti takes a bus to work, crowded amongst different people, dealing with erotic urges, experiencing the flow of time in his individual style — that’s exciting, that’s the real territory of novels, where they do better than other art forms.

3. Your book doesn’t follow a narrative or deal with subject matter that readers, particularly in the West, have come to associate with Pakistani English fiction. Was it difficult to sell this novel to a publisher?

As for my experiences with publishers, there will be a time and place to tell stories not just about Karachi Raj but other books of mine as well. I’ve already suggested what publishers in America are looking for when it comes to narratives of Pakistan and other Islamic countries.

About a decade ago, when I was writing what would become my first published book, Anatolia and Other Stories, a well-known West Coast agent told me, “Anis, the women in your stories are too strong”. They didn’t fit her notion of the weakness, passivity, and insecurity of women in Islamic countries. Indeed, women in my books are generally stronger and smarter than men, as is true of Seema in Karachi Raj.

My fiction doesn’t abide by any of the norms of narrative and plot and characterisation that American publishers expect of a novel of Pakistan. The third narrative stream in Karachi Raj, aside from the points of view of Hafiz and Seema, is Claire the anthropologist negotiating life in the Basti as a foreign researcher.

When I was still writing the novel, an editor at arguably the most prestigious house in the U.S. wanted the entire Claire section to be cut out. Can you imagine Karachi Raj without that crucial third of the novel? It would have become just a story of poor Pakistanis, excising the dimensions of history and social science objectification altogether. The discomfort with the very presence of Claire in the novel was revealing to me.

Similarly, a female Pakistani editor at another top American house, when I had just begun the book, told my agent at the time, “I like realness, butKarachi Raj is too real”. What does that even mean? You can imagine my reluctance to experience any more such ‘expert advice’ from the best and brightest in American publishing. They’re just making up meaningless opinions when the source of their discomfort is the everydayness of the novel’s reality, and all they want is something that justifies their notions of why Pakistan is such a mess.

I was extremely fortunate in finding the perfect publisher for Karachi Raj; it always made complete sense that the book ended up where it did. V.K. Karthika, publisher at HarperCollins India, liked the book the moment she saw it, and it has been a delightful ride ever since. My novel has been appreciated by HarperCollins India for what it is, and the editors at the house totally got the book, they immediately understood the bigger game I was hunting and how and why the details fit in.

The editor I worked with, Manasi Subramaniam, is a brilliant mind who worked with me laboriously over a couple of years to fine-tune the manuscript to the point where we couldn’t make it any better. All the meticulous editing pays off in making the narrative as fluid and clear as possible.

What you want is an editor, as was the case with Karachi Raj, who loves and respects the book but wants to improve it without messing up its authenticity. I’m very proud that publishers in India are leading the resurgence of narratives that make sense for people who experience these realities rather than the fantasia of corporate-induced marketing strategies disguised as ‘books’. These counter-forces in publishing are the most important thing happening in the literary world right now, as the dominance of hegemonic literary capitals and a few narrow imperialist minds needs to be seriously challenged.

4. What’s your favorite memory about the city of Karachi?

Looking back at it now, it’s amazing how little supervision we had as kids and how we thrived and flourished under benign neglect. My maternal uncle, Latif mama, owned a house on Jamshed Road called Mohammed Mahal, where I spent a lot of time as a child with my cousin Razzak. My sister and I would spend the ‘holy nights’— Shab-e-Barat, Shab-e-Qadar — reciting ‘Ya-salamu’ 125,000 times over the course of the night, counting beans.

We wore crisp white kurta-pyjamas and felt very special, lightly supervised by my older cousin Nasser. That mansion had many rooms, some permanently closed off, one where there were sets of drums and musical instruments, saturated with the aura of the Beatles and David Bowie, a world so foreign yet so accessible because of the travels and presence of my uncle’s eight sons all over the world.

In the grand balcony of that same house, when I was three years old, I administered haircuts to my cousin Razzak, while the rest of the family had all gone out, as well as to my hunchbacked, hundred-year-old kaki maa, as she dozed. There was a swing in the garden which we used to ride so high that it still sends shudders down my spine wondering what would have happened had one of us fallen. They had a massive jamun tree, and is there any sweeter sight than a basketful of jamuns freshly plucked off the high branches on a summer afternoon? We used to live off Nishtar Park when I was born, and there were huge jamun trees there as well, but what I remember most is my father taking me and my sister each evening to the lovely garden — it was in pristine condition then — to tell us elaborate tales, among them Quranic stories such as Musa aleyhis-salam throwing his “assa” which became a serpent or Musa aleyhis-salam crossing the Red Sea.

I understand now that a lot of my storytelling instincts must have come from that early experience. I also remember making up endless long stories of magical doings when I was a little boy, enthralling friends at parties I hosted; I remember having no fear of “what comes next”, simply launching into a story and making up more and more fantastical stuff, in a way that I could never do today.

I learned to read, mostly on my own, at an age that now seems impossible to comprehend, and the greatest pleasure was taking in the sun on the balcony, reading and eating fruits and nuts (come to think of it, I’m still doing it!), with my mother a loving presence in the background, letting me do my thing.

I remember the dark side of childhood too, walking in Tariq Road’s Commercial Area once as we encountered a balloon vendor to whom my father didn’t give any money — normally he would have, and the fact that he didn’t on that occasion made me heartbroken, unable to accept that the poor man needed our help.

I was at a clinic with my father when a little boy I was playing with got injured, bleeding from his head, and somehow I understood that he was poorer and would not receive the same care and attention I would.

During the 1971 war we were supposed to cover windows with tape and hide when the air raid sirens went off; at my nani’s house there used to be a massive bed under which I sheltered and went to sleep with my older cousins — twenty years older than me — all of whom I had a crush on. Reader, I slept with my voluptuous cousins who wore the skimpiest of clothes under an exotic bed as the world fell dark and silent.

5. When did you first know you were going to be a writer?

I think this happens in stages, not in a single moment. The summer of 1998 in Houston was the hottest I’ve ever known, as black clouds of minute particles hung in the atmosphere — we were told the soot was the result of mishaps at Mexican plants, but who knows what it really was.

I remember a day in June when I felt at a fatal crossroads: I had already experienced so much at a young age, yet everything left me dissatisfied and empty. I was either going to end my life or I was going to commit myself to writing every moment that remained and not look back.

The epiphany of that moment, the drive generated from it, was so powerful that it lasted about 15 years, all the way until a couple of years ago. For many years after that I apportioned time in minutes and half-hours and hours, and every minute not spent reading or writing I considered wasted.

I decided that one couldn’t even do two things well at a time, let alone three or four, so writing was the only thing I would do, while I shunned friendship, romance, love, everything. To a great extent, this philosophy worked, though I could never be so anti-social today, I desire companionship too even if I’m still torn about it.

During college, I was moving in the direction of being a writer, though I didn’t express it to myself that way, as I explored different options for pursuing a satisfying intellectual life, as a historian, as a social scientist, and abandoned them one after another. When there was nothing left, I realised there was only one thing to do, and that was to be a writer.

I was already in a faraway dreamy world, trying to make sense of how and why novels worked, even though I was nominally a researcher in economics in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the time. Very soon I had the desire to escape that East Coast bubble of sheltered opinions and sheltered lives and I took refuge in what felt like the least literary place in the world, Houston, Texas of the 1990s, to make a life as a writer. I needed an absolute vacuum to create my own reality.

6. You’re currently working on another book, Abruzzi, 1936. What’s it about?

Karachi Raj is a mostly realistic novel — though with a meta-fictional veneer that some critics have just started picking up on — but Abruzzi, 1936 is overtly lyrical, experimental, surrealist. I want to depict that moment of relative innocence (though it was the peak of European fascism so we must be careful to use that term) before the Second World War inaugurated an era of pessimism and cynicism.

In the space of a narrative unfolding over six months, I want to capture the peaks and lows of the humanist experience in the Italian peninsula, the past, present, and future. My characters are a football coach, a physician, a filmmaker, and a professor in internal confinement in a remote Abruzzi village on charges of political sedition.

A village girl whom they’re all fond of dies in the home to which they’re confined, and so the action begins on the night Mussolini has declared victory in the Ethiopian war and the beginning of a new Roman empire…

7. What books are you currently reading? And which ones are on your wish list?

I will mention Orhan Pamuk’s A Strangeness in My Mind. For me, Pamuk is the greatest living writer, the Dostoevsky and Mann and Proust of our time. He wants you to trust your best human instincts, exposing you to unusual characters but then making their extraordinary obsessions feel normal. In imagination lies innocence, and vice versa: this is Pamuk’s great lesson. He is also the best person I’ve met as a writer, with a total absence of pretension or superficial masks. His novels are innocence personified, and so is he. I think that good writing takes place only in a self-prescribed regime of innocence.

Until recently I used to read everything new that came out, and in my era of monkish self-discipline I worked my way through the 20,000 or so books from every genre and period I thought a writer should know, but now I feel only the urge to reread a few classics, particularly the modernists, over and over again: Durrell or Musil or wherever I can find the radical innocence that dares to presume that novels can alter reality.

Mevlut the boza seller in A Strangeness in My Mind and Hafiz in Karachi Rajare both men from poor backgrounds who maintain eternal optimism amidst misfortune in the big city. They both have religiously-inspired names too. I wish I could be half that person in accepting the ups and downs of life.

Karachi Raj

Karachi Raj

Anis Shivani

About half-way through Anis Shivani’s rambling, open, generous novel, Karachi Raj, a photographer named Tipu appears at the home of Claire, an American anthropologist working in the huge slum referred to as “the Basti”. During their conversation, he suggests that anthropologists like her think of people they observe as primitive. She protests, saying that the people from the Basti have a lot to teach.