Ahmed Ali: the borders of language

Mehr Afshan Farooqi

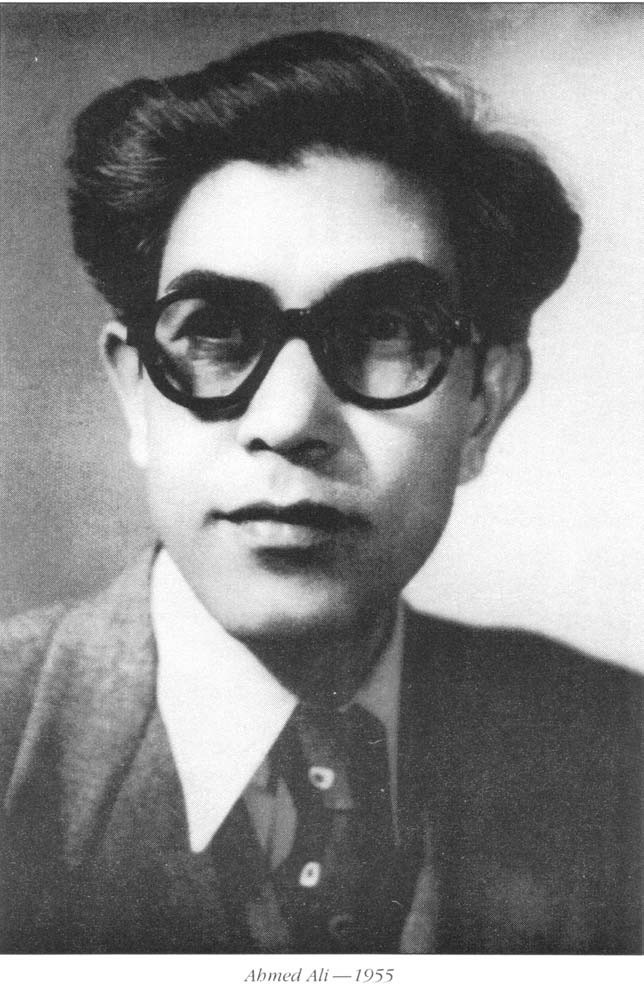

Ahmed Ali 1955

Unpredictably, Ahmed Ali’s birth centenary year (2010) ignited more than cursory interest in his work. The peculiar thing about such celebrations is the particularity of choices. Who gets selected for the fanfare is often pushed more by political exigencies than love and respect for the creative writer.1 Nevertheless, it is remarkable that Ahmed Ali who suffered step treatment from his Angaray brethren and was discounted from the fold of Indian literature (because he relocated to Pakistan) was finally given his due by the Indian government’s premier literary institution, the Sahitya Akademi. Eminent littérateur Harish Trivedi organised a three-day seminar in honour of Ali on behalf of the Sahitya Akademi. The seminar and a bunch of other events brought much deserved spotlight to Ali’s oeuvre.

As a master’s student in English at LucknowUniversity, Ali experimented with writing in English and Urdu. Lawrence Brander, his English professor, encouraged him to translate and publish his Urdu stories in English, which he did. In Lucknow, he met Sajjad Zaheer who inspired him to join the radical group of westernised Muslim socialists. Ali contributed two stories to the fiery anthology Angaray. With Zaheer, he was a founder member of the Progressive Writers’ Association, was closely involved in the planning of the first Progressive Conference held in Lucknow in 1936, and in editing the journal Indian Writing. But two years later he was pushed into separating from the PWA because of differences with Zaheer. Ali felt that art should not become embroiled with politics or it would become propaganda. His understanding of progressivism was more in tune with what he thought was a response to conservatism, that is, liberalism of the socialist-democratic kind, not an explicit Marxist-communist ideological platform. Ali and Zaheer parted ways in 1938. In the summer of 1938, Ali went to Delhi; he returned to Lucknow with his notes and began to write his first novel in English, Twilight in Delhi.

Ali finished a draft of Twilight in a year, encouraged along the way by his mentor Brander who may have suggested that he pursue its publication in England where Ali was headed on a fellowship.3 Ali was not a complete stranger to the literary world of London. He was known to John Lehmann (editor of New Writing) who introduced him to E.M. Forster (1879–1970). At Forster’s, Ali met more writers and poets and became a part of the Bloomsbury group. Forster agreed to read Ali’s manuscript and suggest a literary agent. The Hogarth Press was mentioned; Lehmann was a partner and general manager there. After some initial hiccups, Twilight was published in 1940. The book was widely reviewed in England, and wildly sought after in India, even more so because it went out of print. A second edition was not brought out until 1966.

For a while Ali continued to write in both English and Urdu. Between 1940 and 1945 he published three collections of short fiction in Urdu, Hamari Gali (Our Lane), Qaid Khanah (Prison House) and Maut se Pehle (Before Death), but he also worked on his second novel in English, Ocean of Night. In December 1946, he left for China as a fellow of the British Council, on a quasi-diplomatic mission to teach English literature at PekingUniversity. Seven months later, India’s Partition split his creative world. Ahmed Ali stopped writing fiction in Urdu.

The Partition of India was a life changing event for those who were caught in its vortex. It has continued to exert both a direct and insidious effect on the politics, economics and culture of the region and to some extent the rest of the world. Some have called it the divide between the past and present. Its impact on literary production, especially in Urdu, was significant. Urdu was carried along by its speakers, the Muslims of north India, to Pakistan where it was expected to bloom as the language of the new nation; and it did. Urdu in Pakistan was on a new stage; its background seemed denuded on the one hand, while on the other, it was enriched with the history of the birth of the nation that it would record. For its writers, it presented difficult choices — connectivity with the past or a new beginning.

In Pakistan, Ali married (1950) and opted for a career in the diplomatic service. He also resumed his translation work in earnest. Urdu was the national language of Pakistan; Ali turned his attention to introducing Urdu and its classical literature to a wider, Anglophone audience. In doing so he laid claim to the classical heritage from undivided India. He was the first to introduce Urdu literature to the West. A series of translation projects launched by him resulted in a flurry of slender volumes of poetry, such as The Falcon and the Hunted Bird (1950), The Bulbul and the Rose (1960) and anthology of fiction, Urdu Short Stories from Pakistan (1983). Two decades of translating classical Urdu poetry culminated in The Golden Tradition: An Anthology of Urdu Poetry (Columbia University Press, 1973). Ali’s Golden Tradition was path breaking; it was supplemented with introductory essays that described the development of Urdu as a literary language. His ghazal translations were innovative because he did not match a two-line verse with a two-line translation; he experimented with the virtual space of language as he tried to uncoil and transfer compact ideas encapsulated in the she’rs. He also prefaced translations with biographical and critical notes on the poets. His target audience was the general, educated reader of English.

In the meantime, the first and only Urdu translation of Twilight (Dilli ki Shaam), by Bilqees Jehan (Ali’s wife), was published; a new edition of Twilight was brought out shortly afterwards (Oxford University Press, Delhi and Bombay, 1966). Ali finally published his much revised and awaited second novel Ocean of Night (1964). The book and its subject proved to be uninteresting; not only had the milieu changed but Ali’s audience had changed as well.

What makes Ali’s work interesting to me is the play of bilingualism in his creative work. There are strong resonances between his Urdu and English writing. For example, there are passages from his well known story “Hamari Gali” that are transplanted into Twilight in Delhi. According to Muhammad Hasan Askari, Ali was able to bend and broaden the English language to accommodate Urdu cultural nuances. I had always found Ali’s prose in Twilightcumbersome. It was difficult to read though somewhat charming in its oddness. Why did Ahmed Ali write like he was translating? Was he translating? Was Twilight in Delhi a translation without an original? I am really curious how separate the two languages are in a writer’s mind and how much advantage bilingualism provides with prose syntax.

Ali’s ultimate achievement as a translator is his English translation of the Quran. The popularity of his translation is attested by its publication history: first appearing in print in 1984, subsequently in a second edition in 1986, a “revised definitive edition” in 1988, a “final revised definitive edition” in 1994, and finally in a ninth paperback printing “newly comprising revisions last made by the translator,” in 2001. Translating the Quran seems, for some scholars in Islamic studies, to be the crowning achievement of their career. Ahmed Ali was not a scholar of Islam. He had earned a solid reputation as a translator of Urdu literature; nevertheless, his choice of translating the Quran seems puzzling until one relates it to his lifelong appreciation of the modern mind. Ali’s interpretation of the Quranic text is at times metaphorical. He seems to be engaged in a modernist project to make the message of the Quran relevant to a contemporary global audience.

What is singular about Ali is that he mastered the language of the colonial master without compromising his own episteme, nor adopting that of the protagonist. It comes as no surprise that by the 1970s, the world was ready, and Ali was prepared to offer, unapologetically, his answer to the colonial critique of ‘backwardness’ in the form of The Golden Tradition. It offered proof that tradition isn’t static, but actually progressive, as long as it continues to build and borrow simultaneously. It is also an apt rebuttal of the position his PWA colleagues took with respect to the meaning of ‘progressive’, a position they had co-opted, marginalising him from the very term he had helped formulate. In the final analysis, Ali’s reading of Indian Muslim culture persists, not as simply a moment in time, but as a reading which is not temporally, politically or epistemically bound, but responsive to the internal dynamic of his personal experience — a life imbued with the experience of colonisation, de-colonisation, bilingualism and biculturalism.