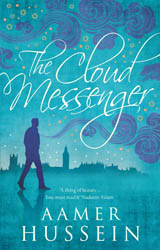

Aamer Hussein

Birth—1955, KarachiAttended Lady Jennings School and the Convent of Jesus and MarySpent most summers with his mother’s family in India Studied in Ootacamund, South India, for two yearsMoved to London in 1970Education: Graduated from SOAS (London University) with a degree in Urdu, Persian and HistoryBibliography

Awards

|

He describes himself as a Karachi born Londoner, has recently published his fifth story collection Insomnia, reviews books for The Independent and the Times Literary Supplement and is contributing editor the literary journals Wasafiri. He teaches Urdu and English literature and translates contemporary Urdu fiction. Also, he is probably the first writer of Pakistani origin to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. In a traditionally British ceremony attended by many literary friends and luminaries, he was asked to sign either with Byron’s pen or Dickens’ quill. ‘I chose the latter, possibly because Dickens was a great story teller,’ Aamer Hussein said the art of storytelling, of conjuring up a myriad of cross-cultural images and compressing his words into tight, nuanced tales is intrinsic to Aamer’s writing. The books that enthralled him as a boy, were not by Dickens, but English translations of French classics by Flaubert, Zola, Gautier, Merimee, Anatole France in the library of his phupi, Mujibunissa Akram, editor of Woman’s World. ‘I always thought of English literature as something to study in class,’ Aamer said. ‘I loved Hardy but I never opened him after I left school.’

Born in 1955, Aamer followed his three older sisters to the Convent of Jesus and Mary’s co-educational junior school. He lived in leafy PECHS amid Turkish, French, English, American neighbours. His father Nawabzada Ahmed Hussain belonged to Sindh. His mother Sabiha Ahmed Hussein came from the princely family of Darbargarh-Dasada in Kathiawar. She loved literature, music and art, was painted by Sadequain and counted many ‘Urdu-daans’ as friends. English was the dominant language in Aamer’s milieu but Urdu was spoken all around him. During a trip to India with his mother, his maternal grandmother insisted on teaching him Urdu ‘properly’; also he glimpsed fragments of an older courtly culture. By 1967 Aamer’s father had started the move to London but Aamer wanted to join his cousin at boarding school in Ooty run by his uncle. He thought spectacular mountainous Ooty would be ‘enchanting’ but turned out to be isolated, stifling and lonely. He arrived in London two years later, at 15. He loved the city’s brilliant cultural life though he was not much enthused by 20th-century English classics such as Graham Greene, Dylan Thomas, T. S. Eliot in his literature classics. In his spare time he devoured contemporary British and American writers from Muriel Spark, Iris Murdoch and Angela Carter to Norman Mailer and William Styron. But these were not writers he wanted to emulate: that influence was James Baldwin. Aamer was particularly interested in the complex emotional relationships in Baldwin’s work and his depiction of being isolated by any difference — racial, sexual or class. ‘When I was in my teens, I wrote stories they were very unrelated to my own life,’ Aamer said. ‘The voice that did come into my head was the narrative voice of James Baldwin, that confessional mode of his.’ In London Aamer also became aware of dislocation, of being cut off from his roots. He travelled to Europe, learnt French and Italian and added Urdu to his A Levels. Briefly he was a trainee banker then opted for a degree in Urdu, Persian and History at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). ‘Until then, I had liked Urdu poetry and I had read some Faiz, Iqbal and Ghalib but I wouldn’t have thought of reading Dakkani poetry or Mir and Sauda,’ Aamer said. ‘I found Anis and the classical marsiya very interesting. I learnt something of narrative technique from there. The classics were a real eye opener.’ Aamer asserts that Urdu is his mother tongue, but English is his first language. He is impatient with people from English-medium schools who complain that their Urdu education was not good enough. He thinks they should find a tutor. He said that Tunisians and Algerians and others seem to work harder to be bilingual. ‘I exercised that option, though Urdu did not come easily,’ he said. ‘I had to struggle to master it.’ He expressed admiration for the work of Algerian writer Assiya Djebar who explores the loss of language suffered by colonised people. ‘That seemed to be the plaint of South Asian writers and I realised that it was my plaint too,’ he said. At first he had difficulty in finding a literary voice for himself in English because its literature is dominated by narratives of Empire. He began to read writers from diverse countries who used English creatively to express their own experiences. He was befriended by the distinguished Chinese-born writer, Han Suyin. She encouraged him to move beyond literary labels such as ‘colonial’, ‘post-colonial’, ‘third world’; and she wrote the preface to his first story collection A Mirror to The Sun (1993). Aamer also came to know Rana Kabbani from Syria, Ahdaf Souief from Egypt, Mimi Khalavati from Iran. He saw films from China, Turkey and Iran. He found translations of Adonis and Darwish. He developed a particular interest in writing from countries which had not been colonised. He read Urdu fiction and loved the writing of Shafiqur Rahman, Ghulam Abbas and Ahjmed Nadeem Qasimi. All this shaped his literary identity ‘that complex interweave of east and west’ central to his work. In 1993, he met Fahmida Riaz. He was very taken by her excellent Karachi story in a special issue of Aaj. The journal included Fahmida’s translation of Aamer’s story of an enchanted Karachi childhood ‘Little Tales’. Her publishing house WADA invited Aamer to give a talk in Karachi on Urdu women writers. Aamer’s interest in the role of gender in Urdu literature had developed when he discovered SOAS archives filled with early twentieth century Urdu women’s fiction. His discovery and interpretation of Muhammadi Begum’s early novels broke new ground in Urdu scholarship and inspired his story ‘Sweet Rice’ about literary memory. Furthermore, his Karachi trip with its combination of the familiar and unfamiliar provided the imaginative landscape for several tales in his second collection This Other Salt (1999). By then Aamer was teaching Urdu at the SOAS Language Centre. His search for contemporary texts had led to him to the fiction of Intizar Husain and Khalida Hussein. He was really excited by their work because it was so modern yet deeply-rooted in Urdu tradition. His own writing began express his dual literary inheritance though he steered away from ‘bazaar’ English. Instead he quietly introduced the structure, style and metaphors of modern Urdu fiction into his English stories. Some became a dialogue between himself and contemporary Urdu writers about history and narrative. This Other Salt includes Aamer’s sophisticated experimental sequence ‘Skies: Four Texts for an Autobiography’, a combination of fiction, poetry and essay about Karachi and Sindh, Partition and other migrations. The expatriate narrator, Sameer visits the city of his magical childhood but is bewildered by its new, fractious strife-stricken society. He ends with the poignant words: “I walk in the narrow hidden lanes of Marylebone, reddish and cobbles for hours and think of you all. Memories like shards of glass, lie shining at my feet in the setting sun. And like glass, draw blood. Then I taste the rain and the salt and the blue distance and I think of the skies of home. Give my love to the sea.” ‘Skies’ includes a character Annie Q. She is later defined as his mother’s friend, Quratul Ain Haider, an immensely important influence on Aamer. His latest collection Insomnia (2007) includes a fine, sensitive and romantic story ‘Angelic Disposition’ which developed from a conversation with her. She had described pre-Partition India where women were gharailoo but well-informed about literature and politics. Aamer portrays a married woman who comes to be known as a scholar and writer. She discovers a kindred spirit in a well-known fellow writer, Rafi Durrani. He is intrinsic to her being, but is killed World War II. Insomnia includes ‘Hibiscus Days’ which knits Karachi and London to look at the expatriate’s relationship with homeland and mother-tongue. The narrator is biographer, translator, friend and rival of Armaan, an Urdu writer. Armaan choses to return to Pakistan; his fellow students remain in England. He is caught in the politics and pulse of his country, which they can only view as observers. The seeds of the story date back some 20 years when Aamer was friendly with a group of politically-engaged expatriate Pakistani students. Often, Aamer has portrayed multicultural London and bonds between migrants from different lands. ‘Crane Girl’ captures student life and the magic and disillusionment of first love; the title story describes the restlessness and wanderings of literary expatriates from Pakistan, India and Jakarta, albeit material success; the ‘Book of Mariam’ challenges today’s erroneous political rhetoric of Christianity vs Islam. While ‘Nine Postcards from Sanlucar de Barrameda’ was written a week after London’s July 7 bombings. Set in Spain where a brilliant Euro-Arab culture flourished once, this elegant, subtle tale is filled with multi-layered images which convey loss and gain, exile, adaptation and cultural commingling. The sunlight reminds the narrator, of ‘a place he once called home’, but the sea is not the same and though there are hibiscus and jasmine ‘there is no frangipani here, that makes it less Karachi’. In this landscape of illusions, his companion but a friend — the woman he loves is but a distant memory as is Pakistan; but there are new colours and horizons to discover yet. Aamer has edited a very fine anthology of Urdu women writers — Hoops of Fire: Fifty Years of Fiction by Pakistani Women (2000), updated and reprinted as Kahani (2005). He has just finished a novella Another Gulmohar Tree. He is also a Lecturer of International Fiction, University of Southampton and Director of MA in National and International Literatures in English at the Institute of English studies, University of London. A Tale of Two Languages by Muneeza Shamsie, Dawn This Other Salt, Tehelka Interviewed by Sana Hussain & Maryam Piracha, The Missing Slate |